In my quest for cameras to review for this site, I’ll occasionally stumble upon some interesting lenses that I pick up to pair with the film cameras they are designed for, but sometimes I like to see what they can do digitally.

There are a huge number of sites filled with lens reviews for both film and digital and while I don’t have the patience, time, or frankly, the desire to give thorough lens tests, sometimes there is a lens I like enough to type something up about it. Such is the case with the Schneider-Kreuznach Tele-Xenar 135mm f/3.5 in Exakta mount that I came across awhile ago. When I bought the lens, it came in it’s original blue Schneider box, which for the life of me, I cannot find, but in the time I’ve had this lens, I’ve shot it a couple of times and have come away impressed with it’s build quality, looks, and performance so I thought I would share with you some sample images and my thoughts on it.

Schneider-Kreuznach is a household name for most photographers and camera collectors, but doesn’t enjoy the universally recognized reputation of lens makers like Zeiss, Nikon, or Canon. Originally formed in January 1913 as Joseph Schneider as Optische Anstalt Jos. Schneider & Co. at Bad Kreuznach in Germany, Schneider quickly became one of the premiere lens makers in Germany, rivaling companies such as Goerz, Voigtländer, Steinheil, Leitz, and of course Carl Zeiss. Schneider Xenon and Xenar lenses became common on some of the best cameras in the world.

The company’s ability to survive two world wars, two complete collapses of the German economy, the rise of both the Japanese and digital camera industries, and still be a relevant optics company in the 21st century is remarkable, so when you have a chance to try out one of their mid century lenses, you owe it to yourself to do it.

The Tele-Xenar was a label applied to a great deal of telephoto lenses made in a huge number of mounts throughout the 20th century. Tele-Xenar lenses were made for 35mm, medium and large format rangefinders and SLRs, you could get them in M39 and M42 screw mounts, using the Exakta, Alpa, Rectaflex, and many other lens mounts.

This particular Tele-Xenar was made with the Exakta mount and although I was unable to find the exact make up of the lens, I believe it to be a 4-element design. Later versions of the Tele-Xenar 135mm f/3.5 had 5 elements but counting internal reflections inside the lens, I can only see 4. Regardless of how many elements there are, this lens is a solid performer.

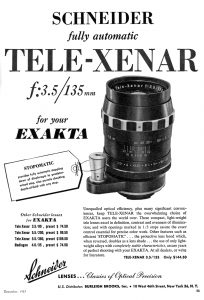

The ad to the right from December 1957 lists the price of this lens at $144.50 which when adjusted for inflation compares to about $1350 making this quite the investment for a photographer looking to upgrade their lens selection to include the 135mm focal length. If 135mm wasn’t what you needed, Tele-Xenars with focal lengths from 90mm to 360mm were also available.

The lens is all metal with no visible signs of plastic or other weight saving materials. The glass elements are single coated and in my example have survived remarkably well, still showing a bluish-purple reflection on the outer element. Like other automatic Exakta lenses, it has an externally coupled shutter release that automatically stops down the iris upon pressing the shutter release. In Schneider product literature, the automatic diaphragm feature was called “Stopomatic”, a feature they also included on the Xenon 50mm f/1.9 Exakta lens.

It supports both automatic and manual operation of the diaphragm by rotating the chrome shutter release. One side of the release button has a red dot and the other side has two black dots. When the red dot is aligned with a second red dot on the mount, the diaphragm is in manual mode. The iris will stop down to whatever is chosen without having to press the button. With the two black dots aligned with the red dot on the mount, the diaphragm is in “Stopomatic” mode in which the iris opens all the way regardless of which f/stop is chosen, and only stops down when the shutter release button is pressed.

The lens has a minimum focus distance of 1.5 meters or about 5 feet which is pretty typical of a 1950s telephoto lens. The focus ring is very wide and on this example, is still smooth with a medium amount of resistance. Focus throw from minimum to infinity requires almost a complete 360 degree turn of the ring allowing for very precise, but slow focus operation.

The aperture ring has click stops at every full stop from f/3.5 to f/22. Later versions of this lens go up to f/32, but I am unsure if the optical formula of those is any different. Between each click stop are two white dots suggesting 1/3 stop apertures, but the lack of any click stops at any of the white dots means you’re most likely going to keep the lens at full stops.

Finally, the front of the lens has a 52mm filter ring, allowing for filters or hoods of that size to be attached. The front lens element sits about a half an inch behind the front lip of the focus ring, so there’s not a lot of built in protection from flare. I never used a hood while testing this lens and never saw flare or ghosting, so that suggests the lens’s single coating is doing a good enough job.

This particular example is in excellent cosmetic condition. The glass has no major scratches, fungus, or haze. Optically, it’s a 10 out of 10. The only issue is a tiny bit of oil on the diaphragm blades which meant stopping down the lens was sluggish, but I overcame this by waiting a second before firing the shutter after selecting a smaller aperture. Maybe one day I’ll have this lens serviced.

To see what the Tele-Xenar was capable of, I shot it as intended, mounted to a Exakta body. I have quite a few Exaktas to choose from, but thought it paired the best with a VX1000 as that was the era these “zebra stripe” lenses were the most common, but it works on any Exakta body.

This first gallery was shot last summer on Fuji 200. It wasn’t until I developed the roll that I noticed the camera had a couple of light leaks, which is very strange as I had shot this VX1000 before and they didn’t show up. I wonder if perhaps I didn’t have the door properly latched or something.

I would guess that anyone searching the internet for reviews of the Schneider-Kreuznach 135mm f/3.5 Tele-Xenar are probably looking to shoot it digitally so I wanted to see what the ole Schneider looked like on digital too. The upper limits of what most film lenses are capable of can’t be seen on 35mm film, so being able to “pixel peep” using a 24 megapixel digital sensor and a large computer monitor is a good test of what a lens is really capable of.

The Schneider Tele-Xenar gave me an excuse to order an Exakta to Fuji adapter. After it arrived, I mounted it to my Fujifilm X-T20 which is a crop sensor camera, which changes the focal length from 135mm to approximately 200mm.

While shooting the Tele-Xenar on my Fuji, I completely spaced out and forgot that the diaphragm has a manual mode by rotating the chrome shutter release button so I had it in automatic mode the entire time, requiring me to both press and hold the Exakta shutter release button, while simultaneously pressing my Fuji’s shutter release to get the lens to the aperture I selected.

Had I simply left it in manual mode, I could have avoided the two handed approach seen in the mirror selfie to the right, but I left this image here so hopefully some of you can have a good chuckle at my expense!

I was quite pleased with the results in both galleries. The digital images show more detail than the ones shot on film as expected, but both galleries have a subtle softness that prevents these images from looking too “sterile” like some optically perfect lenses have today. To some, it might sound contradictory to say that a less sharp lens is ideal, but when shooting vintage glass like this, even the digital images have an analog feel to them that’s hard to describe.

Two things immediately impressed me with these images, the first is the lack of any distracting out of focus details. The three flower shots are all taken at the lens’s minimum focus at between f/3.5 and f/5.6 and the backgrounds progressively become smoother and smoother the farther away from the focus point you go. People who prefer crazy artifacts like swirley or soap-bubble “bokeh” likely would not be a fan of this lens, but I like undefined, creamy backgrounds. Having a digital mirrorless with an electronic shutter capable of up to 1/32,000 is very useful when wanting to test older lenses wide open.

The second thing is the lack of any types of chromatic aberrations which are very common on zoom lenses, and lesser primes. Without getting into a technical explanation, chromatic aberrations are when the various wavelengths of different colors in the visible spectrum don’t perfectly meet up at the same point. This is very common on modern zoom lenses with 10+ elements as this level of correction is difficult and extremely expensive to do. Shooting a simpler fixed 135mm lens with only four elements makes this much easier to control, giving the entire image a very sharp and even look from corner to corner without any of these defects.

The Schneider-Kreuznach Tele-Xenar 135mm f/3.5 lens is never going to win any awards. It will never top the list of “Top 10 Lenses For Petapixel Readers to Buy” and it’s unlikely anything I publish here will crank up the demand for these lenses. The reality is, thousands, probably millions of lenses exactly like this one were produced by Schneider and a dozen other companies over the 20th century that probably all perform the same but that’s OK as I still enjoyed using it.

This particular example is in such nice shape, and feels so great in the hands, and produces results that I really like, that it will remain one of my favorite lenses, even if it’s not very Lens-GAS inducing. I think that if you come across a similar lens and give it a try, you’ll agree too!

Mike, and not forgetting the Retina-Xenar 135mm, which is very much I suspect simply a Kodak rebranding, unless you have info to the contrary.

If you like the physical appearance and design of this lens, and are now the proud owner of an Exakta mount adapter, I suggest you start looking for some Steinheil glass. Back in the day, their Exakta-mount lenses were considered among the best made. And they are handsome as all get out!

I don’t have any Steinheil lenses in Exakta mount, but I do have the Steinheil Auto-Quinon 55mm f1.9 in M42 mount for the Edixa. In fact, that’s the lens on the Edixa Reflex in my review elsewhere on the site. You’re right, its quite good. I’d put it on an even level with the Schneider Xenon 50/2.

Just a dedicated amateur photographer. All S-K Tele-Xenare (German plural ending with an -e) 135 mm share the same optical formula: 2 separated elements on the proximal side of the diaphragm and two groups on the distal side: the front lens and 2 cemented lenses behind it, forming a large “cobble-stone”. Rotelar (Rodenstock) is almost (totally?) identical. It’s what the brochures say and it is true: I’ve just disassembled one yesterday ! The ones in DKL mount can be had for peanuts and are a pleasure to use. The adapters exist for almost all modern digital cameras (even Nikon-F without infinity lens!). Only draw-back: minimum focusing distance is around 4 meter !!!! Very weird at first.

I believe the optical formula of the Schneider-Kreuznach Tele-Xenar 3.5/135 five elements in four groups (1-2/1-1) (https://allphotolenses.com/lenses/item/c_3204.html ); I have it in Exakta mount and in M-42 mount; I had to disassemble the last one so I could verify that this is the composition. A very sharp lens and very pleasant to use.