The late 1930s were an exciting time for Kodak. In 1934 the first commercially available day-light loading 35mm film was released, and was off to a great start as the most popular film format for “miniature” cameras. The German made Kodak Retina series was doing well and was establishing Kodak as a dominant force in camera manufacturing. Kodachrome color reversal film had been released in 1935 and was quickly gaining popularity in both cinema and still photography. Finally, with war in Europe on the horizon, Kodak was frequently being sought after by the US military and it’s allies for aerial and land based reconnaissance cameras and lenses.

During this time of rapid development at Kodak, the company likely had a variety of projects going at once, many of which saw the light, but some that didn’t. Around 1939, Kodak published a two part booklet called Major Developments in New Apparatus, a rather inglamorous name for what was essentially a preview of everything the company was working on.

It is not clear who the intended reader of these booklets were. They were printed on black and white paper without any embellishments that you might expect from proper promotional material. Were these booklets for internal use only, or were they notes for a trade show to give vendors an idea of what might be coming?

I don’t think anyone will ever know what the intent was, but nevertheless, they did get created. The booklet was split into two parts, and the table of contents of the first book lists what would have appeared in the second part, but sadly, the second part seems to have been lost to time. Only the first part is known to exist. At some point in it’s history, it was spiral bound and filed in an Eastman Kodak Library. A hand written date on the first page of 10/3/1979 might indicate the date in which the booklet was filed.

We may never know what was contained in the second part, but based on the table of contents, the second part was a variety of Kodascopes, Projectors, and a Stereo Camera. The first part, which we do have, is almost entirely devoted to still film cameras. Some of these cameras were outlandish prototypes that were never produced, some are early variations of cameras that did eventually get created, and others are near identical to models that did get produced.

With the help of Kodak collector Charlie Kamerman, I bring to you most of Part 1. Pages 19-26 are missing, but otherwise everything is here.

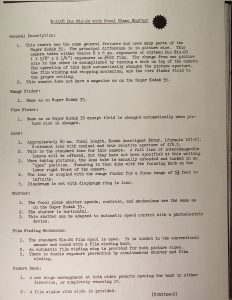

Kodak 35, Motor Drive Model (E-657)

Kodak 35, Motor Drive Model (E-657)

When the Eastman Kodak Company first released their new daylight loading 35mm film in 1934, they chose the Kodak Retina as their first camera to use the film. The Retina was designed by Dr. August Nagel and build in Stuttgart, Germany at Kodak AG, Kodak’s German division.

The Kodak Retina was a tremendous success and would not only help popularize 35mm film, but would start a Retina series of cameras that would last through the 1960s.

The Retina however, was expensive and out of reach of the average photographer, so in 1938 Kodak released an American built 35mm camera simply called the Kodak 35. The new Kodak was built around a mostly Bakelite body with metal top and bottom plates and featured a range of simple to pretty good shutters and lenses. The camera sold well, but lacked some features available in other 35mm cameras of the day, like a rangefinder or interchangeable lenses.

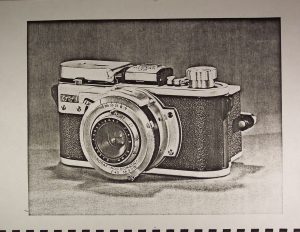

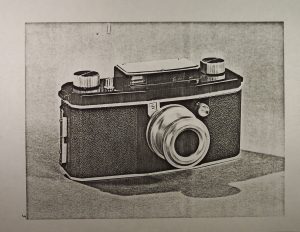

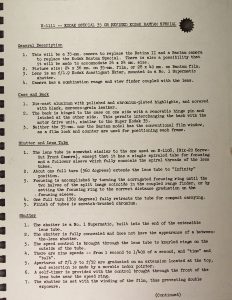

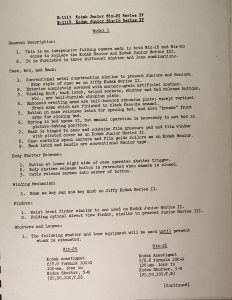

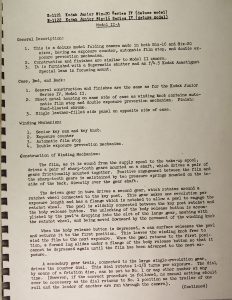

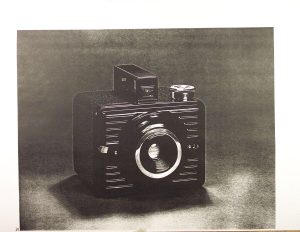

It would seem that upon the release of this camera, Kodak envisioned the 35 to be the first in a series of cameras that would include features not originally available. The first prototype is number E-657, a modified Kodak 35 with a spring wound motorized film back.

It would seem that upon the release of this camera, Kodak envisioned the 35 to be the first in a series of cameras that would include features not originally available. The first prototype is number E-657, a modified Kodak 35 with a spring wound motorized film back.

The description of the camera seems to suggest the Motor Drive Model would have a die cast aluminum body perhaps to save weight, but would also feature hand grain Morocco leather on the back, a feature reserved for Kodak’s top of the line cameras.

The spring wound back would not only advance the film, but would operate the exposure counter and cock the shutter after each press of the shutter release button. A full wind of the motor would be good for up to 6 exposures before needing to be wound again.

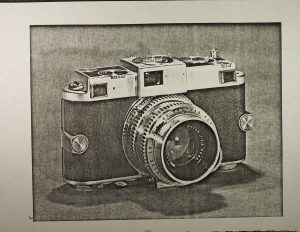

In the prototype image, we can clearly see a much deeper film back which likely contained the motorized parts, and instead of a film advance knob on the top of the camera, is some sort of rectangular box which likely holds the coupling gears and possibly the exposure counter.

What Happened?

Although the Kodak 35 would remain in production past the end of the war, a motorized Kodak 35 was never produced. My best guess is that it was a combination of a feature that likely many customers of the Kodak 35 weren’t asking for, and with the regular Kodak 35 already selling at prices higher than the interchangeable lens Argus C3 rangefinder, a motorized version would have made it even more expensive, likely leading to poor sales.

Another possible contributing factor is the motor wind back looks as though it would have made the camera substantially thicker, making it less portable to be used as a point and shoot family camera.

Kodak 35, Coupled Range Finder Model (E-658)

Kodak 35, Coupled Range Finder Model (E-658)

Further supporting my theory that the Eastman Kodak Company wanted the Kodak 35 to be a series of cameras was this rangefinder equipped version.

In 1939, the Kodak 35 was sold at prices ranging from $14.50 to $33.50 for one equipped with their top of the line lens and shutter. The Kodak 35’s biggest competition was the Argus C2 and C3 rangefinders with interchangeable lenses, which sold for $25 and $30 respectively. Exact sales figures are not available for these cameras back then, but I have to imagine that the Argus cameras easily outsold the 35, and Kodak knew they had to include a rangefinder version.

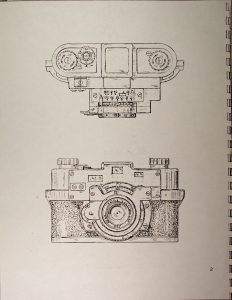

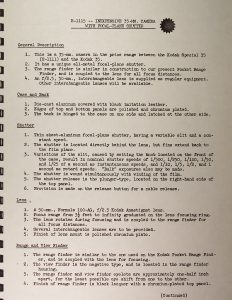

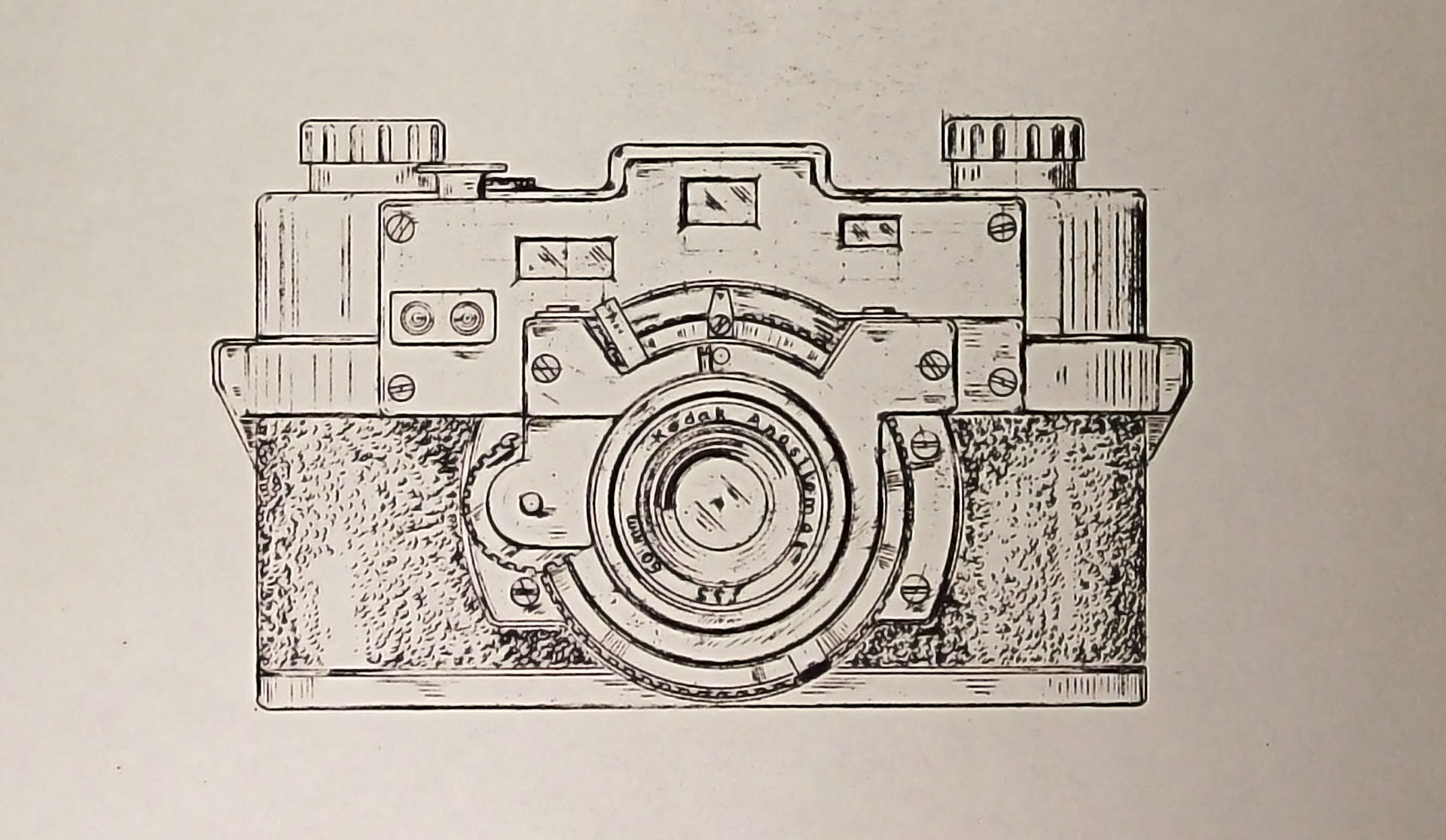

Of all the prototypes mentioned in the Major Developments in New Apparatus book, this is the only prototype shown as a drawing, rather than a photo which suggests it was very early on in it’s development.

Whoever designed the original Kodak 35 did not do it with a rangefinder in mind. Unlike the Argus C-series which was always designed to be a rangefinder, any attempt at adding a rangefinder to the Kodak 35 would require extensive modification to the top plate of the camera. Coupling the rangefinder to the lens would also require some external linkage which can be seen in the two drawings of the camera.

The specifications sheet for prototype E-658 show an entirely new top plate, an external coupling wheel and various other linkages whose purposes are not clear from the drawing.

The rangefinder equipped Kodak 35 would initially be offered only with the f/3.5 lens, but perhaps with the f/4.5 lens later on suggesting the rangefinder would only be a top or near top of the line model in the Kodak 35 series. Otherwise, the camera seemed to be functionally the same as the regular Kodak 35.

What Happened?

Kodak would produce a rangefinder Kodak 35 starting in 1940, but the final version would look a bit different than these drawings suggest. It would seem that Kodak never figured out a way to make a cleanly designed Kodak 35 RF, as the final version had many of the same external couplings and egregious protrusions as the prototype.

Kodak would produce a rangefinder Kodak 35 starting in 1940, but the final version would look a bit different than these drawings suggest. It would seem that Kodak never figured out a way to make a cleanly designed Kodak 35 RF, as the final version had many of the same external couplings and egregious protrusions as the prototype.

Comparing the prototype to the final version, the prototype looks marginally less cluttered, which could possibly be due to some sacrifices needing to be made between the development and production stages, possibly to keep costs down.

Another difference is that the only lens available for production Kodak 35 rangefinders was the Anastigmat Special f/3.5 (later the Anastar) lens. A f/4.5 option was never available in rangefinder equipped cameras.

Today, many people consider the Kodak 35 RF to be one of the ugliest cameras ever made, an assertion I won’t argue against. It’s price in 1943 was $50.50 which was more than any Argus camera and a mere $7 less than the much more advanced focal plane shutter equipped Perfex Fifty-Five which when combined with the camera’s ungainly appearance, must have been a tough sell for many customers.

Perhaps the most ambitious of all prototypes mentioned was the Super Kodak 35. Despite grafting the word “Super” before the name Kodak 35, this camera shared little to nothing with the entry level Kodak 35.

The Super Kodak 35 was envisioned as a top of the line professional camera with an interchangeable lens mount, interchangeable magazine backs, a selection of Kodak’s best lenses, a military designed rangefinder, and a number of other features.

The Super Kodak 35 would eventually go into production, renamed the Kodak Ektra, a camera which I extensively reviewed on this site.

There were a number of changes between the prototype Super Kodak 35 and the final Ektra design, all of which I cover in that article, so rather than duplicate that information here, I recommend checking out my review of the Kodak Ektra for more information.

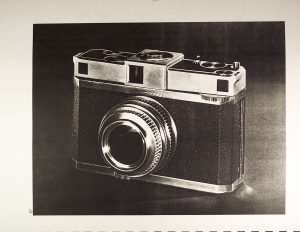

Inexpensive 35mm Camera with Focal Plane Shutter (E-1115)

Inexpensive 35mm Camera with Focal Plane Shutter (E-1115)

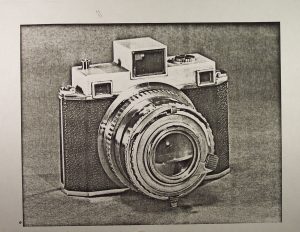

The name of this next prototype hardly rolls off the tongue and would have most definitely been renamed had it gone into production, but is one that I really wish had been made.

Focal plane shutters offer a number of improvements over leaf shutters, including the possibility of higher top shutter speeds, a narrower body, and a more easier way of implementing interchangeable lenses, since the shutter is behind the lens mount allowing for the whole lens to be removed.

The description of this camera suggests a mid range model, priced above the Kodak 35, but below the Kodak Special 35, which itself was seen as a replacement of the Retina II.

The description of this camera suggests a mid range model, priced above the Kodak 35, but below the Kodak Special 35, which itself was seen as a replacement of the Retina II.

Despite the word “Inexpensive” in the name, this camera would have had a lot of ambitious features starting with a cleanly designed camera body which was entirely die cast aluminum with an imitation leather covering and a provision (possibly on the bottom) for a optional motor drive unit.

Equipped with an all metal shutter with speeds from 1 – 1/500, and an interchangeable lens mount, the camera would have had a feature set more comparable to the Perfex Forty-Four or post war Clarus MS-35.

The base lens would have been a Kodak Anastigmat f/2.5 lens with optional 35mm wide angle and 100mm telephoto lenses available later. The documentation does not go into detail as to what kind of lens mount it would have had, but based on the clean looks of the prototype, my guess is it would have been some type of screw mount.

Although not mentioned in the documentation, this camera likely would have superseded the rangefinder version of the Kodak 35 as it would have been designed with an integral rangefinder without any of the protruding external features of that camera.

What Happened?

The specifications of the Inexpensive 35mm Camera with Focal Plane Shutter are really exciting and it’s a shame it was never produced. The quality of the prototype shown look nearly complete so my guess is, at whatever time it was decided this camera wouldn’t be made, it was likely near the end of development.

The Kodak 35 Rangefinder would be released in 1940 and perhaps a combination of so many models in development at once and the looming war in Europe, it was likely decided by the top brass at Kodak that this model wasn’t needed.

The Perfex Fifty-Five sold in 1943 with a Wollensak f/2.5 lens for $69.50 and this camera having a nearly identical feature setup, my best guess is that it would have sold for around this same price, which when adjusted for inflation compares to about $1025 likely making this a tough sell as it’s out of the price range of the casual family photographer, but not good enough to appeal to the pros.

I would have loved to have seen what this camera would have been like to shoot. It’s clean lines and ambitious feature set likely would have made for a really fun little thing.

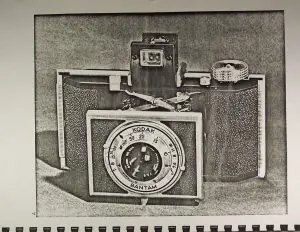

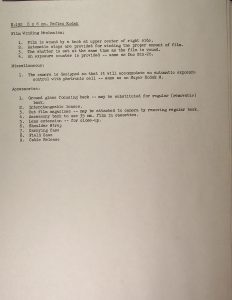

Kodak Special 35 or Revised Kodak Bantam Special (E-1111)

Kodak Special 35 or Revised Kodak Bantam Special (E-1111)

The Kodak Medali…errr wait, Kodak Special 35 or Revised Kodak Bantam Special is a rather curious prototype that looks like a 35mm or 828 version of the medium format Kodak Medalist.

The description of prototype number E-1111 suggests that this model would have been available either in separate 35mm and 828 versions, or perhaps even as a dual format camera capable of using both types of film and possibly even to shoot square 24mm x 24mm images, perhaps with a baffle of some sort.

Looking at the image, the dimensions look exactly like the Medalist, just smaller, so it’s really hard to imagine what this camera would have been like to hold. The top plate of the camera probably would have been similar to the top of a pentaprism SLR, with the sides and back a bit narrower, resulting in what likely would have been an awkward camera to hold.

Like the eventual Kodak Medalist, the entire back of the camera can be removed and replaced with an optional motor drive unit, similar to the one on the Super Kodak 35 (Ektra).

The collapsible lens tube will be a single helix, unlike the Medalist’s double helix and would feature a Supermatic shutter and a non removable 50mm 7-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar f/1.9 lens.

The collapsible lens tube will be a single helix, unlike the Medalist’s double helix and would feature a Supermatic shutter and a non removable 50mm 7-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar f/1.9 lens.

The camera would include a depth of field scale on the camera’s top plate, an automatic exposure counter without exposed film peep hole (for the 828 version), self timer, coupled wide base rangefinder with parallax correction, double image prevention, and a film advance handle (no knob) on the back of the camera, similar to the Super Kodak 35 (Ektra).

What Happened?

Neither the 35mm or 828 versions of this camera were ever produced and my best guess is that the camera was deemed far too advanced and expensive to produce. It’s feature set was probably seen as too similar to that of the eventual Kodak Ektra. My best guess is that leadership at Kodak did not want to compete with themselves by releasing two high spec cameras at the same time.

The Kodak Ektra would eventually go on sale in 1940 with f/1.9 at a price of $300 so it’s not a stretch to think that this camera would have been in the $200 to $250 range, far above the prices typically paid by most photographers of the time. The Ektra was able to compete with precision German rangefinders such as the Leica and Contax, but had this been produced, it would have been in a market by itself, with no clear customer.

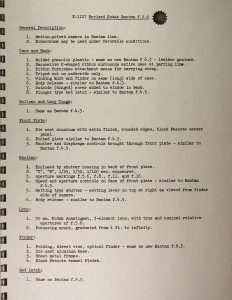

Revised Kodak Bantam f/5.6 and f/6.3 (E-1127)

Revised Kodak Bantam f/5.6 and f/6.3 (E-1127)

The Eastman Kodak Company strongly promoted their 828 roll film format after it’s release in 1935 with the original Kodak Bantam. Originally offered in a solid black plastic body with either an f/6.3 or f/12.5 lens, the Bantams were very compact and inexpensive alternatives to 35mm cameras being sold in Europe.

828 film uses a film stock that’s the same width as 35mm film, but without two rows of sprockets, it allows for a 28mm x 40mm exposed image that’s 30% larger than regular 35mm film, offering slightly more detail. Kodak promoted the use of their new color slide film, Kodachrome in the format and thought that the film would benefit from the larger image when projected into a screen or wall.

The Kodak Bantam series was marginally successful, resulting in several variations all the way up to a top of the line Kodak Bantam Special with a German shutter and Kodak Anastigmat Ektar f/2 lens.

In 1938, a mid range model with an all new folding body and f/4.5 lens made it’s debut, simply called the Bantam 4.5. The Bantam 4.5 had a metal and plastic body, double hinged (scissors) folding mechanism and four speed shutter. When it was designed, Kodak had plans to release f/5.6 and f/6.3 variants to replace the early all plastic f/5.6 and f/6.3 models. These two prototypes would have been less expensive alternatives to the Bantam 4.5, featuring an almost identical body with hinged viewfinder and scissors folding mechanism but simpler shutters. The f/5.6 version would have had a 3-speed shutter that topped out at 1/100 and the f/6.3 would have had a single speed 1/50 shutter.

In 1938, a mid range model with an all new folding body and f/4.5 lens made it’s debut, simply called the Bantam 4.5. The Bantam 4.5 had a metal and plastic body, double hinged (scissors) folding mechanism and four speed shutter. When it was designed, Kodak had plans to release f/5.6 and f/6.3 variants to replace the early all plastic f/5.6 and f/6.3 models. These two prototypes would have been less expensive alternatives to the Bantam 4.5, featuring an almost identical body with hinged viewfinder and scissors folding mechanism but simpler shutters. The f/5.6 version would have had a 3-speed shutter that topped out at 1/100 and the f/6.3 would have had a single speed 1/50 shutter.

What Happened?

Kodak did produce the Bantam 5.6 at a lower cost of $14, but only for a short time. I’ve seen evidence of them in Kodak’s 1939 and 1940 catalogs, but it did not appear in their 1941 catalog. The revised 6.3 model was never produced, however. Instead, Kodak stuck with the original all plastic model and sold it at a cost of $8.50.

My best guess is that the limited production of the 5.6 and non existent 6.3 was a result of decreased demand, due to 35mm film being greatly perferred over 828 film. Kodak would continue producing Bantams through the late 1940s, but only on a limited basis and would discontinue all 828 cameras by the mid 1950s.

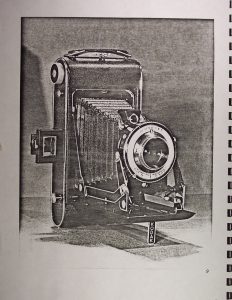

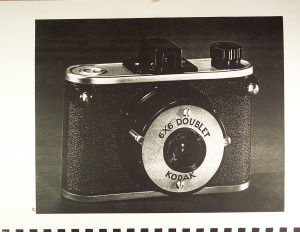

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model I (E-1113 and E-1119)

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model I (E-1113 and E-1119)

Each of these next three cameras are all variations of the existing Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 and Kodak Senior Six-16 and Six-20 that already existed, but with some upgrades.

Both the Kodak Junior and Senior cameras were available using Kodak’s own 620 and 616 film formats, which used a film stock that was identical to earlier 120 and 116 film, but on smaller spools, which allowed the cameras to be more compact.

Kodak was very careful in designing their Six-20 and Six-16 cameras so that regular 120 and 116 film could not be loaded into their cameras. Kodak wanted people who owned their cameras to buy their own film, a habit that they would get into many times throughout the 20th century.

The Model I would have been an entry level camera and has a feature set most closely resembling the Kodak Vigilant including it’s viewfinder, body design, and folding struts. The camera would have been offered with three different lens and shutter combinations, starting with the Kodak Anastigmat f/8.8 lens and 3-speed Kodex Shutter, all the way to the Kodak Anastigmat f/4.5 lens and 5-speed No.1 Kodamatic Shutter.

I’ve never come across an original Kodak Junior or Senior to compare the specs of these cameras to, but at a glance, I don’t see any functional improvements to this new Series IV compared to the earlier models. Cosmetically, the new cameras would have a Morocco grained artificial leather covering, and chromium plated winding knobs, latches, sockets, and release buttons, giving them a luxurious appearance.

I’ve never come across an original Kodak Junior or Senior to compare the specs of these cameras to, but at a glance, I don’t see any functional improvements to this new Series IV compared to the earlier models. Cosmetically, the new cameras would have a Morocco grained artificial leather covering, and chromium plated winding knobs, latches, sockets, and release buttons, giving them a luxurious appearance.

What Happened?

This entry level Type IV Model I camera would be produced as the Kodak Vigilant Six-20 and Six-16, largely unchanged from the prototypes. Kodak would continue to support their 620 and 616 film formats after the war, but I am unsure as to how long these cameras were produced.

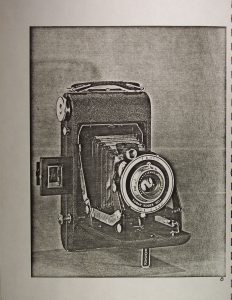

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model II (E-1113 and E-1119)

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model II (E-1113 and E-1119)

This next camera, the Series IV Model II was an upgrade to the Series IV Model I from above which was to replace the very short lived Kodak Special, which I was only able to find in Kodak’s 1937 and early 1938 catalogs.

The original Kodak Special was a top of the line folding camera that had the best shutters and lenses available at the time. Some early Specials could even be ordered with a German Compur-Rapid shutter, in place of the Kodak No.1 Kodamatic shutter.

The description of the Model II said it would use the same construction as the Model I, but with a real leather body covering and polished chromium accents.

The description of the Model II said it would use the same construction as the Model I, but with a real leather body covering and polished chromium accents.

The revised camera would only be offered with the top of the line Kodak Anastigmat Special f/4.5 lens and would no longer be available with the Compur-Rapid shutter, instead with either a Kodak No.1 or No.2 Supermatic shutter with top speed of 1/400.

What Happened?

I found no evidence that a replacement to the Kodak Special was ever produced. Although people still bought folding medium format cameras at this time, the demand for a wide range of features and models wasn’t necessary.

The Kodak Special was only produced for a short time and is hard to find today, suggesting that very few were sold, and had this upgraded Series IV Model II been put into production, it too, likely would have sold poorly.

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model IIa (E-1113 and E-1119)

Kodak Junior Six-16 and Six-20 Series IV Model IIa (E-1113 and E-1119)

Compared to the two Models I and II above, the addition of a lower case letter ‘a’ is all that’s different in this final Six-20 and Six-16 prototype.

But with that little ‘a’ comes quite a few upgrades. This camera, which would become the Kodak Monitor, was a top of the line, fully featured folding camera, complete with a unique all metal top plate, integrated exposure counter, depth of field scale, double exposure prevention, and automatic film stop.

A majority of the camera was the same as the unreleased replacement for the Kodak Special, featuring the same body, folding struts, and Kodak Anastigmat Special f/4.5 lens and Kodak No.1 or No.2 Supermatic shutters with top speed of 1/400.

The camera would have a Morocco grained leather covering and polished chrome accents all over the camera, giving it a deluxe appearance, which would have been expected by a potential customer looking to pay for a premium folding camera.

The camera would have a Morocco grained leather covering and polished chrome accents all over the camera, giving it a deluxe appearance, which would have been expected by a potential customer looking to pay for a premium folding camera.

What Happened?

The Series IV Model IIa would become the Kodak Monitors Six-20 and Six-16, Kodak’s top of the line medium format folding camera. I would put a Kodak Monitor Six-20 through it’s paces in this full review.

In Kodak’s 1940 catalog, the Monitors Six-20 and Six-16 sold for $42.50 and $48.50 respectively, which when adjusted for inflation is comparable to $780 and $890 today making them quite the stretch for the amateur photographer.

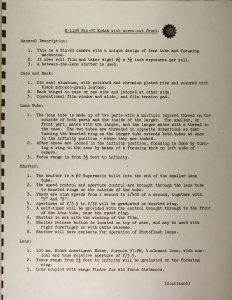

Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front (E-1108)

Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front (E-1108)

Keeping with the pattern of assigning names to these prototypes that are quite a mouthful, we have the Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front, which appears to be a medium format version of the Kodak Special 35 above.

The similarities between the two cameras are very noticeable but with this using 620 roll film, means it was quite a bit larger. The viewfinder and rangefinder system appear to be the same, as does most of the top panel. The screw out front lens uses a double helix for increased precision over the single helix of the 35mm and 828 variant.

The Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front would have many of the same premium features as the Kodak Junior Series IV Model IIa listed above, including an automatic exposure counter, double exposure prevention, and an automatic film stop feature.

The Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front would have many of the same premium features as the Kodak Junior Series IV Model IIa listed above, including an automatic exposure counter, double exposure prevention, and an automatic film stop feature.

The lens would be a 4-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 100 f/4.5 lens and the shutter a Kodak No.2 Supermatic, with speeds from 1 to 1/400.

What Happened?

This camera would eventually be released as the mighty Kodak Medalist. Looking at the prototype compared to the final design of the Medalist, there are a number of changes.

Most noticeably is a focusing arm near the body of the camera and a lack of the precision focus wheel present on the Medalist I. I also see that the integrated depth of field calculator from the Medalist is missing on this prototype. There is also some type of engraving on the top of the viewfinder that is hard to read, but clearly does not say “Medalist”.

Something I find interesting about this prototype is that there exists another prototype, that claims to have been produced in 1939 that also looks like a Medalist Prototype, but looks quite a bit different from this camera.

The image to the left is of another prototype that clearly has many of the same design elements of the finished Medalist, but a completely different type plate. The camera appears to be a rangefinder but with a combined coincident image style, as opposed to the separate view and rangefinders of the finished model.

Whether there were two different designs for what would ultimately become the Medalist or if one of these two prototypes was going to be an entirely different model altogether is not clear. Whatever the case, it seems that Kodak had a lot of interest in a solid bodied Six-20 roll film camera with premium features and their top of the line lens and shutter.

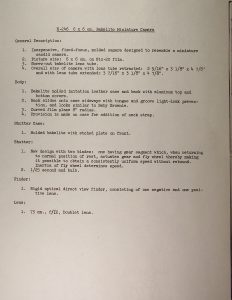

6x6cm Bakelite Miniature Camera (E-246)

6x6cm Bakelite Miniature Camera (E-246)

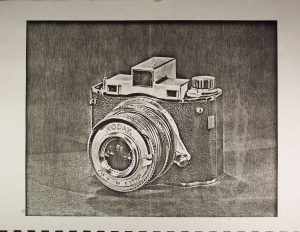

Proving that Kodak didn’t just design premium cameras, this 6×6 Bakelite Miniature Camera was clearly designed for the entry level of the market.

Described as an inexpensive, fixed-focus, molded camera, it was designed to resemble a miniature candid camera, except it shot 620 medium format film.

Featuring a 73mm f/12 Doublet lens, a curved film plane, and a two blade single speed shutter, this camera was aimed at the bottom end of the market. Entry level cameras like this still had a place for those not willing (or able) to invest a lot in a photographic camera. The relatively large size of the 6×6 negatives meant that contact prints could be made without the additional cost of enlarging them.

Featuring a 73mm f/12 Doublet lens, a curved film plane, and a two blade single speed shutter, this camera was aimed at the bottom end of the market. Entry level cameras like this still had a place for those not willing (or able) to invest a lot in a photographic camera. The relatively large size of the 6×6 negatives meant that contact prints could be made without the additional cost of enlarging them.

This was a no frills camera that likely would have been marketed to children or amateur film students wanting to get started with photography.

What Happened?

This camera would be released in 1940 as the Kodak Duex at a price of only $5.75, the camera was produced until 1942 and sold reasonably well but was not continued after the war.

Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter (E-1106)

Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter (E-1106)

Further evidence that nothing was off the table in Kodak’s design department comes this curious camera which was essentially a medium format version of the Super Kodak 35. Think of it like a Kodak Ektra 620.

Described as having the same general features and using many of the same parts as the Super Kodak 35, this thing was a dual format camera, capable of both 6×6 and 6×4.5 images selectable by turning a knob on the top of the camera.

The viewfinder, rangefinder, focal plane shutter, exposure counter, depth of field scale, self timer, and body coverings are all identical to the Super Kodak 35.

Where the two cameras differ (other than film size) is the lens would be a unique 6-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 80mm f/2.3 lens with a full line of interchangeable lenses offered (although none specified). It is not clear if the camera uses the same lens mount as the Ektra, but my guess is it wouldn’t have since the lenses would be larger and the design of the prototype looks less cluttered than that of the Ektra.

Where the two cameras differ (other than film size) is the lens would be a unique 6-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 80mm f/2.3 lens with a full line of interchangeable lenses offered (although none specified). It is not clear if the camera uses the same lens mount as the Ektra, but my guess is it wouldn’t have since the lenses would be larger and the design of the prototype looks less cluttered than that of the Ektra.

The Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter would not have a magazine back like the Super Kodak 35 and would have a double side hinged door that can be opened from either side, rather than the bottom like on the Ektra prototype.

What Happened?

Sadly, the Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter would never be produced. I’m a huge fan of the Kodak Ektra, giving it high marks in my review for it, so I’m fascinated at the thought of there being a medium format version of the same camera.

I have to imagine that the reason for this camera never being released is that it would have directly competed with both the Kodak Ektra and Medalist. It likely would have been priced in between the Ektra which sold in 1940 for $300 with the f/1.9 lens, and in the Medalist which sold for $176. A price between $200 and $250 would not have been out of the question.

These were premium cameras with premium price tags, so the potential customer base was already limited and for Kodak to have offered a third premium model would have not only confused customers, but likely would have sold very poorly.

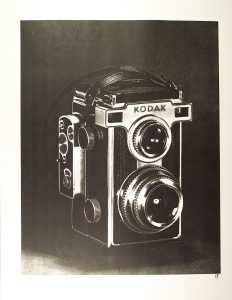

Without a doubt, my favorite of all the cameras in this article, the 6x6cm Reflex Kodak looked to be a top of the line Twin Lens Reflex camera with features from other premium prototypes like the Super Kodak 35 and Six-20 Kodak with Screw-Out Front. Think of it like a TLR version of the Ektra or Medalist.

I used to think that Kodak completely ignored the TLR market in the 1930s, choosing not to compete with the Rolleiflex and Rolleicord but the existence of this prototype paints a different picture.

The 6x6cm Reflex Kodak would have been a Rollei killer, featuring things that no German TLR had, such as a split image rangefinder inside of the ground glass waist level viewfinder. There are no images of what this would have looked like but it is described as being in the same field of view as the main viewfinder, along the top edge. The entire viewfinder offered automatic parallax correction.

The shutter was a focal plane shutter, rather than a leaf shutter like on most TLRs and was linked to the film wind mechanism, setting it as you advance the film.

The camera also had, are you ready for this, an interchangeable lens mount featuring a selection of lenses “probably” the same as the Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter (Ektra 620). The base lens was a 6-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 80mm f/2.3 that was both faster than anything the Germans were offering in any of their TLRs and could focus down to 12 inches.

The camera also had, are you ready for this, an interchangeable lens mount featuring a selection of lenses “probably” the same as the Duo Six-20 with Focal Plane Shutter (Ektra 620). The base lens was a 6-element Kodak Anastigmat Ektar 80mm f/2.3 that was both faster than anything the Germans were offering in any of their TLRs and could focus down to 12 inches.

Of course all of these features were in addition to “regular” TLR features such as an automatic exposure counter, double image prevention, auto stop film advance, and an eye-level “sports finder” with some type of collapsible mirror system in the hood.

Had enough yet? There’s more. The 6×6 Reflex Kodak would have supported a number of accessories including an automatic exposure device with Photronic cell. You read that right, an optional exposure meter could be added to the camera allowing for automatic exposure….on a TLR…in 1939!

The entire back of the camera was removable, allowing for a sheet film back, a 35mm film back, or an optional ground glass back for precision work. The interchangeable lens mount would have supported lens extensions for macro work

What Happened?

Oh man, what ever did happen to this camera. Reading the description and specifications of this camera makes me agonize to hold one. It’s almost like someone was looking at a menu of camera features and checked every single box and said “I want everything”.

I can only assume that the extremely ambitious list of features for this camera was simply too great. The amount of engineering and development that would have been required to make a camera like this was probably beyond Kodak’s reach.

In Central Camera’s 1943 catalog, they advertise a Zeiss-Ikon Ikoflex 3 with f/2.8 Tessar lens for $219, but that camera lacks a rangefinder, an interchangeable lens mount, and a focal plane shutter. My best guess is had the 6×6 Kodak Reflex gone into production, it likely couldn’t have sold for less than $250, possibly even comparing to the Ektra’s price tag of $300, which if that were true, would have meant it was the most expensive medium format camera sold by any manufacturer, anywhere in the world. As cool as this camera was, it likely would have sold veyr poorly, a fact that likely led to it never being released.

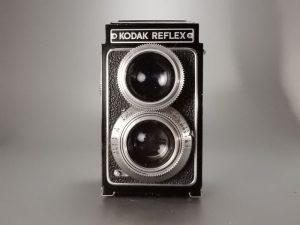

After WWII, Kodak would eventually release a proper TLR with the name Kodak Reflex, but it would hardly be the fully featured monster suggested by this prototype. It was a relatively simple camera with Kodak’s 4-element Anastar taking lens, externally coupled gears, and a bright waist level finder.

Still, knowing that at least one prototype of this camera was built, it’s plausible this thing still exists somewhere in the world, but where is it?! I can’t imagine the prototype is functional but if it is, I really hope it shows up some day.

Inexpensive Six-20 Brownie (E-244)

Inexpensive Six-20 Brownie (E-244)

The Inexpensive Six-20 Brownie gives us a look at a possible alternate design for their entry level 620 box cameras This camera likely would have been a replacement for the earlier Six-20 Bullseye camera.

The description of this camera suggests it would only cost 75 cents to make, which considering the Bullseye’s $3 price lines right up with what this camera might have sold for.

With a molded body and stamped tin front plate, the camera would have been light weight, and with a single shutter speed and single element 97mm f/16 lens would have been able to deliver an extremely wide depth of field for focus free operation.

With a molded body and stamped tin front plate, the camera would have been light weight, and with a single shutter speed and single element 97mm f/16 lens would have been able to deliver an extremely wide depth of field for focus free operation.

The most curious thing about this camera is the rigid metal handle on top of the camera that also doubles as the viewfinder. I’ve never seen a Kodak camera with this design before, but I have to image it would have been very easy to clean!

What Happened?

As best as I can tell, this camera was never built. I looked through various US Kodak catalogs from 1939 – 1942 and saw nothing like it. Kodak did have a habit of releasing some cosmetically different variants of their cameras in Europe, so there’s a small chance this camera was sold as some type of British Kodak, but I doubt it.

The more likely story is that Kodak decided they had enough inexpensive 620 cameras and simply didn’t need another.

The only camera in this entire article with a non-prototype sounding name is this Baby Brownie Special. With a feature set identical to that of the regular 127 format Baby Brownie, the Baby Brownie Special has a few cosmetic embellishments.

Rather than a folding wire frame viewfinder, the Special gets an optical direct finder sealed inside of the rigid plastic top plate. The film advance knob and horizontally mounted plunger style shutter release are both made of an ivory plastic material called “Tenite”.

Finally, the entire body received a stylish vertical pattern that looks fancy, but doesn’t actually enhance the operation of the camera.

What Happened?

The Baby Brownie Special was likely already completed when this book was produced, which is why the prototype looks identical to the finished model. It would first appear in Kodak’s October 1939 catalog with a 25% premium over the cost of the regular Baby Brownie. What was the cost of these cosmetic enhancements? 25 cents. The Baby Brownie Special sold for $1.25 compared to $1 for the base model.

If you’d like to know more about the Baby Brownie Special, check out my full review of it.

Final Thoughts

I think the most fascinating thing about prototypes is to get a glimpse of what might have been. In the case of cameras like the 6×6 Kodak Reflex or the Inexpensive 35mm with Focal Shutter cameras, I think these would have been fascinating to use, but for reasons that I can only theorize about, were never made.

If you’d like to read about more prototypes that were never created, check out the following Keppler’s Vault which covers an article from February 1964 about some Voigtländer prototypes that were never built.

And finally, the Major Developments in New Apparatus book in it’s entirety. If you’d like to download it for yourself, there is a download link in the control panel at the bottom of the PDF.

Mike, what a truly fascinating article and, oh boy, that TLR was something else!

You asked what happened? I believe I can readily say it would have been prohibitively expensive. What market would it have been aimed at, and even then, how many would have been able to afford it?

Also, it would have been so complex that failure rates may have been too high for even Kodak to contemplate. (Think Zeiss Contarex.)

It’s akin to all those concept cars we see, and which no doubt would sell like hot cakes, compared to the toned-down boring cars they turn into.

Terry, your comment is logical, well thought out, and probably correct. But I don’t want logic! I want to shoot one of these Kodak TLRS! 🙂

In all seriousness, yes, the cost would have been astronomical and the reliability would have been suspect…sounds like the Ektra!

Mike, as a dyed-in-the-wool TLR man myself, I totally agree! I’d have given my right arm, well almost, to have had the chance to play with it.

What might have been! And I’m with you on the prototype TLR — wow! Can you imagine these prototypes sitting somewhere in a cabinet or drawer just gathering dust and slowly falling apart? What a shame! Thank you for all of the work condensing the info from the book and making it an enjoyable read!

My Dad bought a Kodak 35, probably shortly after WWII, and it became my first camera 20-some years later.

I used it for several years and probably didn’t notice what an ergonomic disaster it was, having nothing to compare it to.

You focused by putting your finger on the spiney-sharp gear wheel on the right side of the lens; the shutter release was a fiddly little lever low on the lens, and you had to kind of search for it every time. And on and on. I don’t think the Kodak engineers ever tried to use one before it went to market.

It’s odd, because they did have the Contax and the screw-mount Leicas to look at, at least. How hard could it have been to have a smooth focus ring around the lens, and maybe put the shutter release on top, where you can find it every time.

On the other hand, the lens was pretty good. I made a lot of 8×10 prints (a big deal for me at the time) that still look fine.

Remarkable find, that book of “what if’s”. The Kodak TLR reminds me of the Contaflex TLR in terms of complexity and likely selling price. (For the SLR version of a similar overly-ambitious camera, see either of the Exakta 66 models that were sold just before, and just after, WW2. Both flopped in the marketplace).

Regarding the handle / viewfinder on the model E244 Inexpensive 620 camera: Check the first model of the Cine Kodak 8 movie camera. Same design, but collapsible (folds flush).

I have to wonder, among all the prototypes in this book, why there was no continuation of the Kodak Super Six-20 or similar folding auto exposure camera. Surely, the engineers at Kodak could have thought up a way to add features to that camera, interchangeable lenses, etc. or was the camera too much of a failure from its 1938 release to warrant further development?

Kodak should have made the upper end cameras in medium format, 120 roll film. The Medalist and Chevron. The TLR with a leaf shutter but otherwise, same idea should have been produced. 120 would have helped sales by advanced amateurs and pros alike.

As much as I want to agree with you that I wanted to see Kodak stick with their upper end cameras, the reality is, Kodak was a film first company. With rare exception, all cameras that had the name Kodak on it, were built to sell more film. Kodak didn’t need to keep making upper end cameras like the Ektra or Medalist to keep selling film, they needed more Signets, Motormatics, and Instamatics. With the benefit of hindsight, it worked! But yeah, I would have loved to see what a whole series of Ektra or Chevron cameras might have looked like!