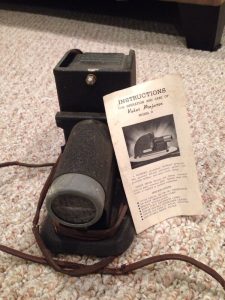

This is a Vokar II, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Vokar Corporation from Dexter, Michigan between the years of 1947 and 1948. It was a very ambitious American made rangefinder camera that boasted a lot of value for the money, including an entirely Vokar designed lens and shutter with speeds from 1 second to 1/300. It’s other features include a large (for the era) and bright coincident image rangefinder system, auto cocking shutter, and double image prevention all in a compact and sleek metal body. The Vokar II was an update to an earlier Vokar I in name only, as there are no differences between the two models. The camera sold poorly and suffered from poor quality control causing the entire Vokar Corporation to go into bankruptcy by the early 1950s.

This is a Vokar II, a 35mm rangefinder camera made by the Vokar Corporation from Dexter, Michigan between the years of 1947 and 1948. It was a very ambitious American made rangefinder camera that boasted a lot of value for the money, including an entirely Vokar designed lens and shutter with speeds from 1 second to 1/300. It’s other features include a large (for the era) and bright coincident image rangefinder system, auto cocking shutter, and double image prevention all in a compact and sleek metal body. The Vokar II was an update to an earlier Vokar I in name only, as there are no differences between the two models. The camera sold poorly and suffered from poor quality control causing the entire Vokar Corporation to go into bankruptcy by the early 1950s.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2.8 Vokar Anastigmat coated 3-elements

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Vokar Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/300 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 876 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/vokar_i.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Vokar is an attractive and ambitiously featured camera created by a new company created by ex Argus employees. The camera features a combined coincident image rangefinder, a shutter with speeds from 1 – 1/300 and a quality triplet lens. Despite it’s good looks, due to some questionable design choices, the camera quickly developed a reputation to be unreliable. I had access to three different Vokars for this review, and although I attempted to fix them all, I had problems with all three. This is a very good looking camera that looks great on a shelf, but not much else. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.1 | ||||||

History

The Vokar Corporation was one of many American companies that produced cameras in the 1930s and 1940s who would release innovative designs meant to fill a disruption in supply from Germany after World War II. Vokar’s history is most closely related to Argus, who was another American maker of cameras and other photographic equipment. The two companies were both based in the state of Michigan, and at one time were located less than a mile away from another.

Vokar was founded by ex employees of Argus, but which employees founded it is a point of confusion. Some sources on the Internet suggest that Vokar was founded by Charles Verschoor who was the man who founded the International Radio Corporation, or IRC, which was the company that Argus would become. In the early to mid 1930s, IRC made a wide variety of tabletop and portable radios using Bakelite plastic, but saw a need to branch out into other markets when sales began to slow due to the depression. In 1936, Verschoor and IRC would release their first camera called the Argus A which was such an immediate success, the entire focus of the company shifted from radios to cameras, and resulted in a name change from IRC to Argus.

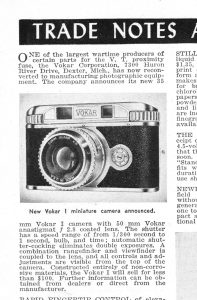

The other man credited for founding Vokar was an Argus engineer named Robert Wuerfel who worked at Argus at the same time as Charles Verschoor and is listed on the Articles in Incorporation in the state of Michigan for the Electronics Products Manufacturing Corp. The two men likely knew each other as well, further adding to the confusion, but Wuerfel’s signature on signed documents puts this debate to rest.

The name “Vokar” refers to a brand of Bakelite bodied folding cameras that shot 6cm x 6cm images on 120 roll film produced by the Electronics Products Manufacturing Corp. These were basic folding cameras that came in a variety of configurations, often using Wollensak shutters and lenses, but also sometimes appearing with Argus designed Ilex shutters. A later version of the Vokar folding camera called the Vokar B was produced starting in 1946, which is easily identified by having metal top and bottom plates.

Both the Vokars A and B were sold under a variety of names, some for the department store chain Montgomery Wards, but also using the brand names Voigt (not to be confused with the German company Voigtländer), and Wirgin.

Camera production was halted during World War II, likely to aid in the American war effort. In 1943, the Electronics Products Manufacturing Corp would relocate 8 miles away to Dexter, Michigan, and in 1945 would change it’s name, officially becoming known as the Vokar Corporation.

After the war, in addition to releasing the Vokar B folding camera, the Vokar Corporation would begin work on an ambitious new 35mm rangefinder camera which would eventually become the Vokar I. According to the book, Glass, Brass, and Chrome: The American 35mm Miniature Camera by Kalton Lahue and Joseph Bailey, the design of the Vokar I was started prior to the war by another ex-Argus employee named Richard H. Bills. While this may be true, the same book also goes with the story that Vokar was founded by Charles Vershoor, which I do not believe to be correct.

The post-war camera industry was very unique for American manufacturers as supply from almost every German manufacturer was disrupted due to supply problems. The Japanese camera industry was still in it’s infancy, so there wasn’t yet a huge export market for Japanese cameras, leaving the United States as the sole source to fill the need of returning soldiers who wanted to buy a camera.

Companies like Eastman Kodak and Argus were already well equipped to pump out new models, but there was a huge influx of smaller companies like the Universal Camera Corporation, Clarus, Ciro, Perfex, Utility Mfg. Co. (Falcon and Spartus), Whitehouse Products Inc (Beacon), and many others who attempted to fill the void with American made cameras and other photographic products.

The challenge that almost all of these companies faced was that most were founded by ex employees of other optical companies who might have had knowledge about camera design, but few had any real world experience in precision manufacturing required for a high end camera. This resulted in most American cameras being inexpensive and having simple designs that were quick to develop and manufacture and cheap to sell. The postwar manufacturing capabilities of American companies was geared towards large scale production of automobiles, tanks, airplanes, and other war related products, not small precision products like cameras. There was little to no industrial experience for optics beyond what already existed from companies like Wollensak and Kodak.

As a result, many of the more ambitious designs created by companies like Clarus, Perfex, and Vokar were met with major quality control issues plaguing the reputation of each company’s early products. The story of many of these companies is almost exactly the same. A new model was announced shortly after the war touting a revolutionary American made camera with features that compared to existing German brands, but sold at a fraction of the price. These announcements almost always followed with a delay in said products becoming available and when they did, they each had major issues with quality control, necessitating manufacturing changes along the way. In each instance, the new cameras would eventually get their kinks worked out by the end of the decade, but by then, it was usually too late and almost all of these companies would disappear by the early 1950s, just in time for an onslaught of new and exciting Japanese cameras to hit the market.

Of all the American cameras introduced after the war (the Perfex was in production prior to the war), the Clarus MS-35 and the Vokar I were probably the most ambitious, although both pursued different designs. The Clarus took many cues from the Leitz Leica II camera and had an interchangeable lens mount, a fast focal plane shutter, and a dual viewfinder/rangefinder design. The Clarus was one of the more expensive American made 35mm cameras with a list price of $122 upon it’s release. Although not very successful, it managed to stay in production for nearly 6 years.

The Vokar had a completely different design than the Clarus, using a non-removeable lens and a leaf shutter, contained in an all metal body with a unique shape that some have suggested reminds them of a Streamliner locomotive.

What is most surprising about the Vokar I was that everything, including the shutter and lens, were built by Vokar themselves. The company did not outsource anything to Wollensak or other optics companies as was common by almost every other American manufacturer at the time. The Vokar leaf shutter was a very unique design that camera repairman Rick Oleson describes as:

Vokar designed and manufactured their own shutter for this camera, and it’s a very unusual construction: both the aperture and shutter blade sets are contained in a single drop-in module, while the entire timing and actuating mechanism is in another preassembled module that occupies only half of the available space in the housing.

While unique in design, the Vokar’s shutter had the advantage of being able to shoot at speeds as slow as 1 second, something most other American cameras couldn’t do. According to Rick, the design of the shutter was quite good, but possibly due to the inexperience of the company, they were often plagued with quality control issues. The lens was a coated anastigmat triplet constructed in 3 groups. I do not know if the Vokar lens was based on any existing lens formulas, or if it was an entirely new design.

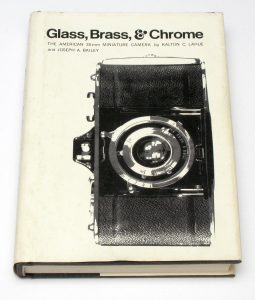

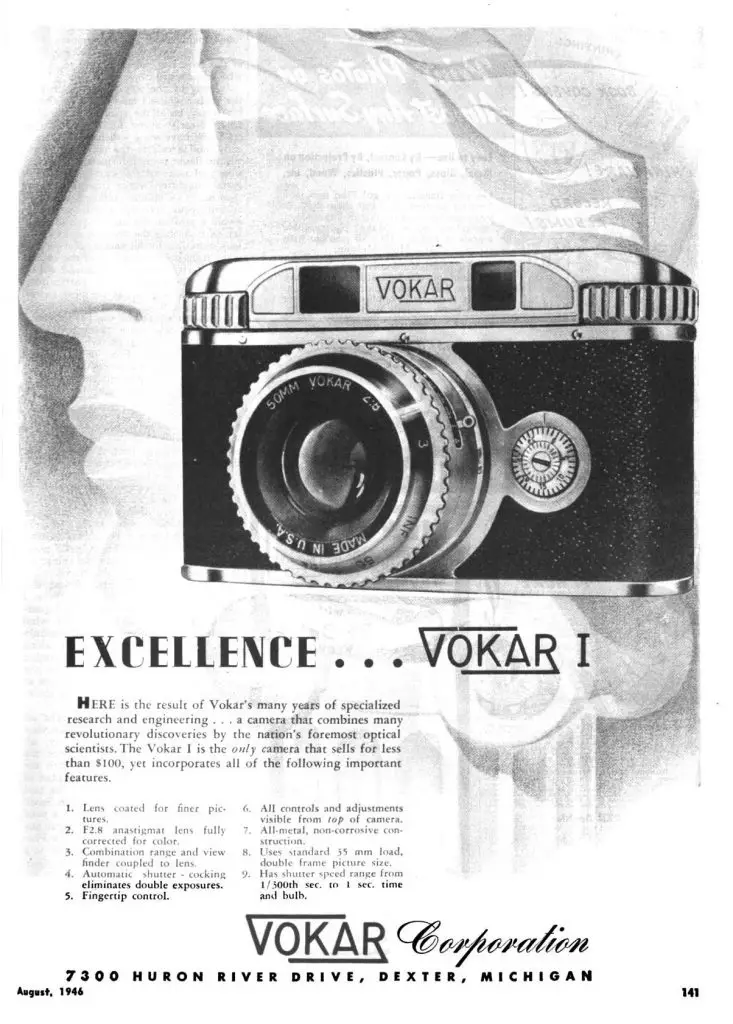

The first appearance of the Vokar I was in ads posted in the January 1946 issue of Popular Photography. The camera was revealed to be the Vokar I and an image of the new model which very closely matches the final product was included with a list of 9 selling points. The ad claimed that the new Vokar camera “combined many revolutionary discoveries by the nation’s foremost optical scientists.” The ad goes on to claim that it would be sold for under $100, although no exact price was given.

Although advertised in January, the camera would not be available for nearly a year later. It is unknown what caused the delay or why Vokar stopped advertising the camera for nearly half a year. When the camera re-appeared in ads in August 1946, the list of specs was unchanged, as was the same image of the camera from the January ad. I can only assume that the ambitious design of the camera, it’s shutter, or it’s lens caused some type of manufacturing problem.

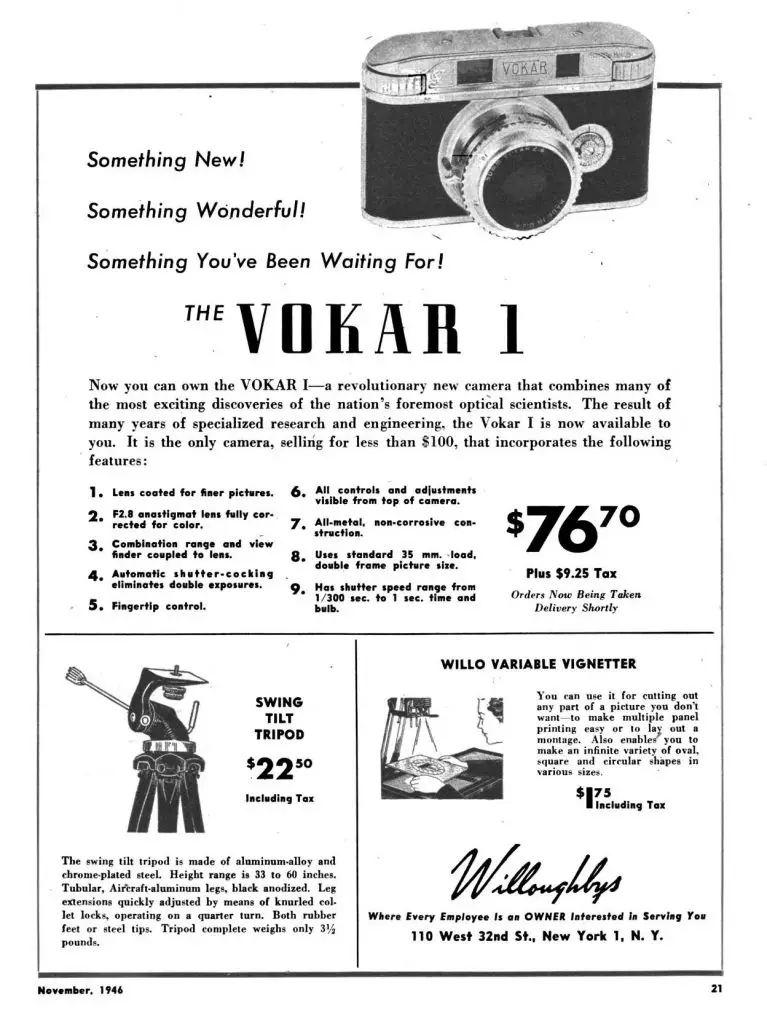

By the fall of 1946, new ads for the Vokar I appeared, this time with a list price of $76.70 plus tax, which when adjusted for inflation is about $970 today. An advertisement in November 1946 for Willoughby’s Camera in New York lists the same $76.70 price and says that orders are now being taken, with delivery “shortly”. Whether there was still a delay, or that demand was too high for supply is anyone guess, but it’s safe to say that it’s unlikely many Vokar Is were under Christmas trees that year.

By early 1947, the Vokar I seemed to be making it into customer’s hands as I found evidence by scouring archived issues of Popular Photography using Google Books, and saw the camera appear on price sheets for many camera stores across the country including Olden Camera, Central Camera, and many others. While prices remained around the $80 mark, some were advertised in the $90 range, but it’s possible that included the case and some other accessories.

I could not find any information about how well the camera sold, or how many were made. Information about the Vokar camera is very hard to come by on the Internet and in the limited images I saw of Vokar Is on sites like Google and Flickr, none have a serial number higher than this one which is 6418. There is no way to know how many were made, or if the first models started at serial number 1, but assuming they did, its probably safe to estimate that fewer than 10,000 Vokar Is were ever made. Considering how rarely these models show up for sale, my guess is that the actual number is much lower.

The Vokar I was produced until at least December 1947, when reference the Vokar II started to appear in catalogs. The earliest references to the Vokar I always included the “I” in the name which suggests that a model II was planned all along, however upon the release of the Vokar II, it seems nothing changed, other than the appearance of the name “Vokar II” printed on the leather skin.

In my research for this article, I found far more examples of the Vokar II than the Vokar I suggesting it was produced in much greater numbers. Of the three that I had access to for this review, the lowest serial number is 0277 and the highest was 7095.

Comparing my three different Vokar II’s, I did notice a few minor cosmetic changes to the outside appearance of the camera, and a few functional improvements under the hood, which confirms the notion that the Vokar was continually updated along the way. I’ll go over the differences I’ve found later in this article.

It is interesting to me that a Vokar II exists that is almost identical to the Vokar I. Was a more advanced Vokar II planned all along, but due to production problems with the first model, all upgrades scrapped? Perhaps the Vokar I was never meant to have a sequel, but due to some early quality control problems, Vokar made the decision to re-brand the camera with a new model number in the hope that people would see it as an improvement, when in reality there was no difference? These are all good questions that we’ll likely never get the answers to.

As I alluded to earlier in this article, Vokar would struggle in the marketplace. On paper, the specs of the camera were well within it’s price range, and assuming the quality control issues were solved, the camera should have been quite successful. The Vokars I and II had a very good coincident image rangefinder at a time when many cameras, including the Leica still relied on separate viewfinder and rangefinder windows. The shutter’s top speed of 1/300 certainly wasn’t top of the line, but it was comparable to other very popular models like the Argus C3 and many mid-level German cameras.

Perhaps people weren’t ready for an ambitious American made camera, or the initial poor reputation of the camera was too much to overcome, or perhaps it was just poor marketing, but regardless of why, the Vokar can best be described as an ambitious failure. Although I believe the Vokar II sold in higher quantities than the Vokar I, it seems to have disappeared from catalogs in late 1948 with only a passing mention in ‘used equipment’ sections after that.

Vokar did have a lineup of somewhat successful slide projectors that sold at Sears and other US department stores and they did make other products for the photographic market, and I found evidence that these products continued after the 1940s, but it seems that the Vokar II was their last attempt as a camera maker. Their name faded from view in the early 50s, and according to camera-wiki, the company was dissolved in 1964.

Today, it’s hard to say whether or not the Vokar I or II are sought after by collectors because they’re so uncommon, many people don’t know they exist. They rarely show up on eBay and as of the writing of this article, none were for sale and there was only one sold auction in whatever time range eBay allows you to search. So to come up with an estimated worth for these cameras is difficult.

For those out there like me who have an interest in post-war American cameras, these are some of the coolest out there. The Vokar camera has a very attractive design that looks like no other and certainly could be a featured camera in any collection. If you ever have a chance to pick one of these up, even in poor condition, consider yourself lucky as they don’t show up often.

Repairs

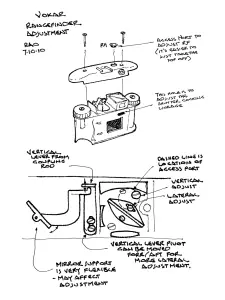

The Vokar, like most American cameras, is a simple design that’s relatively easy to repair. I mentioned having three of them and I took apart all three for various reasons. I had to clean the lenses, flush the shutter, align the rangefinder, and clean the viewfinder glass and mirrors. When I first acquired these cameras, I never planned on opening them up as far as I did, but after talking to Rick Oleson and seeing his hand drawn schematic of the Vokar, I decided to give it a try.

This next section will be unlike my typical Repair discussions where I won’t give you step by step instructions as I am quite certain that anyone with the tools and rudimentary skills to open up a camera, should be able to figure it all out. Instead, here are a bunch of repair pictures with my comments on what I’m doing in each.

The first step in repairing the Vokar is to remove the front lens grouping. This requires removing the front metal focus ring, by backing off three set screws that are in small holes on the side of the ring. Do not completely remove these tiny screws as they are lost easily and will be very difficult to get back in.

The first step in repairing the Vokar is to remove the front lens grouping. This requires removing the front metal focus ring, by backing off three set screws that are in small holes on the side of the ring. Do not completely remove these tiny screws as they are lost easily and will be very difficult to get back in.

Behind the focus ring will be a long metal rod. On two of the three Vokars, this rod had a small hook on one end, the third was straight like in the image to the left. This rod is what moves the the rangefinder as you change focus. Set it aside.

Next is the outer lens grouping. This lens grouping controls focus, so pay attention to it’s orientation so you can put it back together without having to collimate. You can make a notch at top dead center if you like. Once you are sure you have your mark, simply unscrew this grouping and set it aside.

Next is the outer lens grouping. This lens grouping controls focus, so pay attention to it’s orientation so you can put it back together without having to collimate. You can make a notch at top dead center if you like. Once you are sure you have your mark, simply unscrew this grouping and set it aside.

Behind it is a metal ring with the middle lens element with spanner notches on the side and a wavy metal bushing. Remove these two and set them aside. They will most likely be very dirty, so this is a good time to clean them.

Once you get the middle lens element, you have access to the diaphragm. Be very careful with these and don’t dislodge them as they’re very difficult to get back into position.

If you want to flush the shutter, you can stop here and try to flush it still in the camera, but unlike many other leaf shutter cameras, getting the whole shutter out of the Vokar is quite simple, and its more effective to get it completely out, so I recommend continuing, but if you want to stop here, that’s fine too. Before I get to removing the shutter, we should remove the top plate.

On the Vokar I and earlier Vokar IIs, there are two screws that go straight down through the center of the top plate. If this is how yours is, remove these two screws to remove the top plate. On most Vokar IIs, there are a total of four screws, two in the front and two in the back that need to be removed to take off the top plate. Whichever one you have, remove the screws and lift off the top plate.

On the Vokar I and earlier Vokar IIs, there are two screws that go straight down through the center of the top plate. If this is how yours is, remove these two screws to remove the top plate. On most Vokar IIs, there are a total of four screws, two in the front and two in the back that need to be removed to take off the top plate. Whichever one you have, remove the screws and lift off the top plate.

With the top plate off, this is a good time to clean the viewfinder and rangefinder glass. The diagonal mirror on the right side is the beamsplitter, so be careful not to rub it’s semi-reflective coating off. There are horizontal and vertical adjustment screws on the base plate of the beamsplitter that you can use to calibrate the rangefinder.

At this point here is everything you’ve removed (the rod from behind the focus ring is not shown).

At this point here is everything you’ve removed (the rod from behind the focus ring is not shown).

To remove the rest of the shutter you’ll need to remove the back of the camera so you can see into the film gate. There is a lock ring with spanner notches holding the rear element in place that needs to come out. I did not have difficulty getting a standard lens spanner to grip these notches on any of the three Vokars.

After removing the rear element, remove the three screws around the perimeter of the shutter opening and the entire thing comes out. In the first image below, you can see the metal rod above the screw which is the same rod that you previously removed when taking off the front focus ring (I shot these images out of order). The large curved assembly to the right is the shutter cocking mechanism.

Place the shutter face down on the table and looking at the back of the shutter, there will be a black metal plate with 3 long brass screws. Remove these and lift off the black plate.

Once the 3 screws are removed, the shutter can now be separated into two distinct halves. The shutter’s clockwork gearing mechanism is the silver colored “half moon” part, and the brass piece is the diaphragm and shutter blades in their own separate assembly. The chrome plated outer lens barrel can be lifted off and set aside. The clockwork gearing can be lifted off as well. Pay attention to the orientation of these pieces when lifting them off as they need to go back together the same way during reassembly.

With the clocking gearing and blades out, they can each be cleaned using naphtha or whatever shutter solvent you prefer. Here are a couple more shots of the clockwork gearing, and it soaking in a glass dish.

At this point, the Vokar can be thoroughly cleaned and put back together. Make sure the clockwork gearing is completely dry before putting it back into the camera. You may even want to use a very small amount of lithium or synthetic grease on the pivot points. Inspect the diaphragm and shutter blades to make sure there’s no damage and that they can move freely.

If the film advance knob doesn’t move freely, you may want to inspect the shutter cocking mechanism in the film compartment. The Vokar is a simple camera and most of these pieces just need to be clean of old grease and dirt and put back into the camera the way they came out.

My Thoughts

Vokar cameras are quite uncommon. I don’t know if I’d go as far as to say rare as there always seems to be one or two for sale at any given time on eBay (as I type this, there’s actually four), but with prices all over the map, finding one in good condition at a reasonable price can be tricky.

I was on a passive lookout for one, but one day I had the opportunity to buy not one, not two, but three Vokars all for a reasonable price. Two of them looked to be in really nice shape and the third looked rough, but I didn’t care, and within a couple of days they were mine.

When they arrived, they all needed work of some kind which I talked about in the previous section, but the good news was that they all shined up quite nicely, even the rough one was able to be salvaged into a respectable display piece.

I did not realize until handling the camera for the first time, how large and heavy the Vokar is. Many American made cameras of the era used weight saving synthetic materials like Bakelite in their construction, but not the Vokar. This camera is made entirely of metal. Weighing in at 876 grams (just under 2 lbs) the Vokar is heavier than an Argus C3 at 766 grams or even an Ihagee Exakta (body only) at 732 grams.

The upside to all that weight is that the camera has good balance and a really nice tactile feel. The viewfinder is large and bright, the two knobs that are used for film advance and rewind are solid pieces of machined metal, and the front mounted exposure counter looks great as well. This is a very good looking camera, and likely one of the prettiest American made cameras ever.

The top plate features an accessory shoe, and nothing else. There are two screws that hold the plate on, which on later Vokars were replaced by four screws on the front and back of the top plate. Even with those cameras, the two screw holes are still there, just plugged up with metal blanks.

Flip the camera over and you have a sliding door lock for accessing the film compartment and a 1/4″ tripod socket off to the side. While I don’t know that many Vokars were ever used on a tripod, I have to wonder if not centering the tripod socket was a bad idea. The camera’s heft would likely throw off the balance when mounted to a cheap tripod.

With the back off, we see the very shiny film compartment. The inside plate of the camera strangely has a mirror-like finish that actually caused me trouble trying to capture the image to the right. Film travels from left to right onto a fixed take up spool with a metal clip for securing the leader. Unlike nearly every other 35mm camera I’ve ever seen, the sprocket shaft is on the supply side of the camera, and not the take up spool. This causes two side effects, both of which are evidence of an inexperienced company who didn’t quite make the best decisions.

Normally, these shafts in 35mm cameras are used for two purposes. One is to advance the exposure counter, which it does here. But the other is to make sure that frame spacing remains constant throughout an entire roll of film. When you have a new roll of film in a camera, the take up spool has a narrow diameter and requires more revolutions to advance one full frame. As you take pictures and more film is on the take up spool, it’s diameter increases, meaning that it doesn’t have to rotate as much to pull out the correct amount of film to keep the exposures properly spaced.

The Vokar doesn’t do this. The take up spool is designed in such a way that it always rotates one full revolution before stopping for the next frame. This means that as you go through a roll of film, your frame spacing will keep increasing. By the end of a 36 exposure roll of film, the gaps are so wide, you’ll likely wouldn’t be able to capture 36 images on the roll.

The other issue with the Vokar’s film transport is that this sprocketed shaft always spins in both directions. There is no “forward” or “reverse” modes for film transport. This means that the film can be rewound at any point throughout a roll, without having to press a button or slide a lever to allow for reverse film transport. Care should be taken not to touch or obstruct the rewind knob with film loaded in the camera, as it could cause exposures to overlap.

The exposure counter is on the front of the camera and is a simple dial with numbers from 0 – 34, which suggest the designers were aware of the frame spacing issue on the camera since you won’t ever get a full 36 exposures out of the camera. The exposure counter does not automatically reset and must be manually turned to 0 after loading in a new roll of film.

Most of the camera’s critical controls are on the front of the camera. There are separate red-tipped levers for controlling shutter speed and aperture f/stops, each set using a sliding lever on opposite sides of the lens barrel. On the same side as the f/stops is the shutter release lever. The shutter release is in a comfortable location and is easily reached by the index finger of the photographer’s right hand. Immediately below the shutter release is a threaded hole for a shutter release cable.

One shortcoming of the Vokar is the minimum focus distance of only 4 feet. This is rather surprising given the almost 360 degree rotation of the focus ring. I have to imagine that this limit was due to the rangefinder’s design as even the simplest 3-element lenses of the era should have been able to go down to 3 feet or less.

The Vokar’s viewfinder is quite large and bright, especially for a 1940s American camera. The rangefinder uses a coincident image via an internal beamsplitter that’s large compared to the rest of the viewfinder, but unfortunately lacks contrast, making it difficult to see in all but the best lighting situations.

There’s a lot to like about the Vokar’s looks. It is clear the designers started with a clean slate, and didn’t borrow anything from any existing cameras on the market. The rounded corners of the body loosely mimic that of the original Leica, but even that’s a stretch.

What I like the most about the Vokar, is that unlike other American models by Perfex and Argus, I believe that the people behind this camera had a pretty good idea of how a camera should work. The body had nice symmetrical curves, the viewfinder was large and bright, all of the camera’s critical controls are in easy reach around the shutter, and didn’t settle for off the shelf lenses and shutters and built their own. Of course having the desire to build a quality product and actually doing it are two different things.

My Results

Having three of the same camera affords you the benefit of choosing the best one to play with. Two of the three Vokars seemed to be in perfect working order when I was done messing with them so I picked one of those and shot a 24 exposure roll of Kodak Gold 200 film on a nice early summer day. While shooting that roll, I noticed that after the 24th exposure, I could still advance the film. I kept shooting, and shooting, and shooting. By the time I reached what would have been the 30th exposure, I knew something was wrong. I rewound the film back into the cassette and developed it.

Not only was I have film transport problems, causing over half of the roll to overlap on top of one another, there were light leaks and focus issues on most of the images. In the gallery below, I picked out 5 of the images that were the most salvageable. It would take me nearly 9 months to get around to wanting to shoot the Vokar again. I noticed that the take up spool seemed to have some play in it and the rangefinder had stopped working on that one, so I double checked the other “good” one, and decided to use that. For that roll, I chose an expired roll of Kodak Panatomic-X 25.

Although I shot two complete rolls of film in the Vokar, I was unable to get through either roll without film advance problems. It would seem that between the two cameras I used, both had an issue where after about the 10th exposure, the film started to slip progressively overlapping the next image more and more until a point where the film would no longer move at all.

Frustratingly, the second roll was shot on a trip to Northern Michigan to visit family where we passed through a small town with many charming old towns where I shot what I thought would be some really cool photos. There was a whole sequence of about eight photographs that I scanned below and although they all overlap, you can make out some pretty neat photos.

I really wanted to like the Vokar. I have a soft spot for American made cameras and with the Vokar’s great looks, “one and done” story, and unique shutter and lens, I thought this might be a camera that I would want to come back to time and time again.

Unfortunately, things don’t always work out as you hope. I didn’t enjoy using the camera. The right eyed viewfinder was awkward to use and the recessed advance and rewind knobs, as cool as they look, are not easy to use. Top an unpleasant shooting experience with back to back film advance failures, and I don’t think this camera will get a third roll.

To be fair though, this is a 70+ year old camera, produced by a company with very little camera experience, at a time where camera design wasn’t as standardized as it would later become. The Vokar is a cool camera, and if I were to look past it’s failures and imagine what it might have been capable of in good working condition, the images above do hint at a fairly capable lens and shutter.

In the black and white images specifically, there’s quite a bit of sharpness with little to no softness or vignetting at the edges. I’ll go on a limb and say the Vokar Anastigmat was on par with anything Wollensak or Kodak were producing at the time. The Vokar shutter maintained speed correctly and gave me properly exposed shots. Although I didn’t try to shoot any at 1 second, the fact that it’s even possible is remarkable.

In some ways, the Vokar is the exact opposite of an Argus. Where the Argus was an extremely capable camera where design took a backseat to functionality, the Vokar is a beautiful camera where it’s clear design won out in some areas over functionality. But that’s where sites like mine get to ignore all of that and declare what turned out to be a nearly inoperable camera with several poor design choices, something that I am still happy to own. There are many reasons to collect old cameras, their looks, their history, and their performance, and well, the Vokar does two out of three of those quite well!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Vokar_I

http://wphs-tucson.blogspot.com/2009/06/argus-vershoor-and-vokar.html

https://www.flickr.com/search/?user_id=26262745%40N08&view_all=1&text=vokar

Very interesting review, Mike, and the illustrated repair sequence is much appreciated. I bought a Vokar II in 2006 because it is American-made, and it features very attractive styling. As I recall, I paid about $75 on That Auction Site. I sold it to a German collector a year later for about the same money. Woulda shoulda coulda held onto it … when you find a Vokar today you can flog it for $400, which puts it in the same league as a working Leica IIIf. Remarkable!

Thank you for this fascinating piece of history. I have often wondered why America never matched the German and Japanese success in high quality cameras when it led the world in so many other areas.

When you consider the design of American cameras of the era, this is some handsome camera. And from what I can see from your images the fairly simple lens is a good performer for a triplet.

I’d like one, but not at all at the silly prices being asked.

Keep looking, I do see them come up for sale now and then. I sold two of the three in this article, the highest one went for $75 which I had hoped would have been more, but that was clearly the most anyone was willing to pay at that time.

Mike, the overlapping exposures and free-spinning sprocket shaft sound like a loose film tensioning. Are you sure the shaft never had a spring of some sort or another device to tension the film as it was advanced?

I don’t think so. Having seen 3 different Vokars, they all seem to work the same way. The camera does not have a “rewind mode” like pretty much every other 35mm camera. To rewind film, you simply turn the rewind knob, opposite of film travel to overcome the take up spool and rewind the film. I just think that over time, the amount of tension to overcome the film transport loosen over time to where normal film transport slips and it cant travel the film correctly. I’m not saying there isn’t some way to fix it, as it’s not something I attempted on mine, and maybe one day I will. But since I did manage to get at least a couple of frames, I thought I could finish the review with some thoughts and then move onto the next camera! 🙂

the filmtransport shaft has a washer in it, a ‘friction washer’, so you can advance the film, but do not touch the rewind wheel (says the original manual), because this causes to cock the shutter wihout winding the film, the film reel would slip, as it does when you rewind the film.

Mine was crumbled (btw: oil would be poison)

cheers