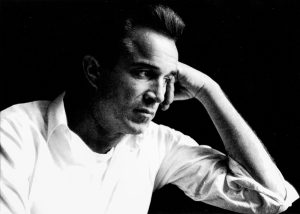

David Douglas Duncan passed away on June 7, 2018 at his home in France at the age of 102. One of the most famous photographers of the 20th century, his works have been seen all around the world, most commonly while he worked for LIFE magazine. He photographed the Korean War, Pablo Picasso, Nixon, Vietnam, and many other important people and events.

There are a huge number of other articles on the Internet celebrating the life and career of Duncan that go over his many accolades and show many of his most famous works. Each of those stories are well worth reading, and are just a simple Google Search away.

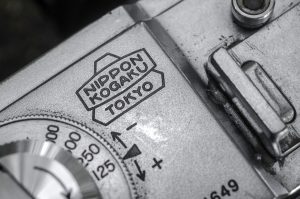

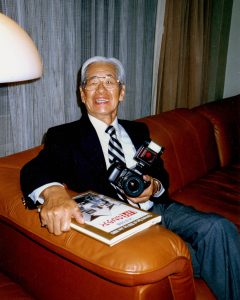

For this article, I wanted to focus on Duncan’s role in popularizing Nikon (then called Nippon Kogaku), and to a lesser degree, the entire Japanese camera industry. I recently sat down with Nikon historian, collector, and president of the Nikon Historical Society, Robert Rotoloni.

Robert shared his knowledge with me regarding Duncan’s role in helping to popularize Nippon Kogaku cameras and Nikkor lenses in the early 1950s. He says that while Duncan was a talented photographer, he was an even better promoter. He warns that contrary to popular opinion, David Douglas Duncan was not solely responsible for the popularization of Nikon, and didn’t discover it himself, rather it was a combined effort from a variety of people in and around Tokyo right before the Korean War who helped make the world aware of Nippon Kogaku.

The story starts with US occupation of Japan right after the end of World War II. General MacArthur was in charge of operations to assess future Japanese potential for post war prosperity. Even before the war, the United States saw great potential in Eastern Asia and had established many military bases in and around the far East. Part of the reason for Japan’s entry into World War II was to stop the US advance of military supremacy in the Philippines, Korea, Guam, and other island nations. Maintaining a stronghold in the east was still a priority after the war, so the United States had a stake in turning Japan into an ally and rebuilding their economy to help boost US strength in this region.

Nippon Kogaku had made nearly all of Japan’s optical products during the war such as binoculars, scopes, gun sights, and had amassed a large workforce of very talented engineers and laborers. The US surveyed Nippon Kogaku’s potential for economic growth and decided that they had the right amount of potential to help kickstart the Japanese economy.

When Nippon Kogaku’s factories resumed production under US guidance, they were forbidden from making anything for the Japanese military, so instead, their first products were consumer binoculars, eye glasses, and eventually cameras. Since the Japanese economy was in shambles, there were few in Japan who could afford to buy any new products made by Nippon Kogaku or anyone else, plus it was more important to bring in American money, so nearly every early Nippon Kogaku product was sold for export.

By restricting the sale of cameras and lenses as export only meant that American money could flow back into the Japanese economy and allow them to rebuild faster. The original run of Nikon I and M cameras were never sold domestically in Japan, and only in very rare instances given to Japanese hospitals and other scientific businesses.

Because of this, Nippon Kogaku was not well known to Japanese photographers and other world photographers that were stationed in Tokyo at the time. Despite being made there, the average Japanese citizen had never heard the name “Nikon” before.

At the time, the US military used “Post Exchange” or PX stores where US service men and women could buy a variety of goods tax free while they were stationed in Japan. Contrary to popular belief, Nippon Kogaku did not utilize the PX system for it’s earliest cameras. It was not until the very end of Nikon M production before the first Nippon Kogaku products were first offered through PX stores. Robert says that he has only seen two Nikon Ms with a PX logo, and even then, they were early Japanese logos, not the standard diamond EP logo.

Rather than use the PX system, Nippon Kogaku attempted to utilize American importers to sell their cameras in the United States directly. A San Francisco based camera technician named Adolph Gasser was one of the first American businessmen to show interest in selling Nikon cameras in the US. After receiving his first sample, Gasser would show the camera to a New York based colleague named Marty Forscher who thought it was a nice camera, but had a few shortcomings, most notably the 24mm x 32mm exposure size. Forscher was much more interested in the Nikkor lenses and turned to a highly respected lens testing expert named Mitch Bogdanovitch who bench tested the lenses and declared them to be as good, if not better than Zeiss lenses, to which other colleagues thought he was crazy!

The non standard exposure sizes of the Nikon I meant that they would not fit into Eastman slide holders and ultimately meant that the Nikon I had to go back to the drawing board. It is commonly reported that up to 750 Nikon Is were ever made, but Robert says the number sold was actually closer to 400, with some being early prototypes that weren’t sold, and about 250 later modified and sold as Nikon Ms.

Nikkor lenses enjoyed a bit more success at this time as other Japanese companies like Canon, Leotax, and Nicca all offered Nikkor lenses as standard equipment on their respective Leica Thread Mount cameras. The Sears Roebuck Company imported Nicca cameras with Nikkor lenses and sold them in the United States under their Tower brand.

In the late 1940s, LIFE Magazine was the premiere news publication for international news stories. Only the best photographers shot for the magazine, and to be chosen came with a lot of respect. In 1946, a photographer named Horace Bristol was one of the first LIFE photographers to be stationed in Tokyo. He was charged with shooting the rebuilding of Japan after the war. He was joined in 1947 by another man named Carl Mydans, and together Bristol and Mydans provided LIFE with many photos about Japanese culture and the state of the country.

Like nearly all professional photographers at the time, Horace Bristol and Carl Mydans shot German cameras. Bristol favored Contax rangefinders and lenses, and Mydans the Leica III and it’s lenses. Although Nikkor lenses were used on a variety of Nikon mount and Leica Screw Mount cameras at the time, they weren’t taken seriously by professional photographers. The overwhelming opinion at the time of Japanese made goods was that they weren’t up to par with the high German standards that pro photographers were used to.

That all changed in early June 1950, when another LIFE photographer named David Douglas Duncan who was in Tokyo assigned to shoot a series of photos about Japanese art, had a meeting with Horace Bristol in LIFE’s Tokyo office.

A young Japanese photographer named Jun Miki, who was the first Japanese photographer welcomed into LIFE’s “inner sanctum” had borrowed a Nikkor 85mm f/2 lens from his friend and mounted it to his Leica III and shot a couple of casual photographs of Duncan and Bristol.

Duncan recalls this encounter and told the young Japanese photographer he was wasting his time as the lighting in the room they were sitting in was poor. As it would turn out, Miki wasn’t wasting his time, as he quickly developed and printed the roll, and the next day returned with several 8x10s of the photos he had shot the day before.

Upon viewing the large prints, Duncan was amazed at the quality of the images. Remembering that Miki had shot these with a Leica, he asked to see the lens that he used and Miki then showed him the Nikkor 85/2 lens he had borrowed. “Nippon Kogaku…who is that”, Duncan wondered. Miki responded by saying a local Japanese company was producing these lenses, and upon hearing that the factory was in nearby Shinagawa, he asked for a tour.

Jun Miki then reached out to his contacts at Nippon Kogaku and spoke to then-president Dr. Masao Nagaoka, who arranged for a tour with Miki, Duncan, and Bristol. The three men jumped into a cab and visited the factory. Upon seeing the quality and attention to detail that went into creating the Nikkor lenses, they observed a few being tested on a optical bench, and the results were superior to anything they had previously seen by Leitz or Zeiss. Both Duncan and Bristol were so impressed with the quality and performance of the Nikkor lenses, that they left the factory with three lenses, the Nikkor 50mm f/1.5 (the f/1.4 lens didn’t exist yet), 85mm f/2, and 135mm f/4 all in Leica Thread Mount.

Barely a week after this tour of the Nippon Kogaku factory, war broke out in Korea and both Duncan and Bristol were sent to Korea to cover the war. Using their newly acquired Nikkor lenses, the two men shot the entire war using their new Nikkor lenses. As was standard practice back then, photographers would shoot a roll of film, develop them, and then send the negatives back to the home office in New York for publication. Shortly after receiving Duncan’s film, he received a telegram from the home office questioning what he was using to shoot this film as the sharpness was better than anything they had seen prior.

Robert mused about a story of one instance where the lab had noticed what they thought was a speck of dust on one of the negatives that they couldn’t wash off, so they enlarged the negative to a much larger size to see what it was, and it turns out is was a helicopter in the distant sky.

As word started to spread through various LIFE offices, photographers started to take notice of Nikkor lenses. Soon, many other photographers such as Carl Mydans, Howard Sochurek, and Hank Walker were shooting them which only increased their popularity. Nikkor lenses were available in both Leica Thread Mount and Contax Mount, so many of these photographers who favored German cameras could easily mount a Nikkor lens and start shooting. In the case of Hank Walker, he was one of the first to give the actual Nikon rangefinder a try.

Hank Walker was impressed with the build quality and fluid controls of the Nikon, especially during the winter months. Average daily temps in December through February in Korea are below freezing, and Walker later commented that the Nikon cameras were extremely reliable and performed just as well in the cold as they did in the warmer months. Eventually, other photographers like Margaret Bourke-White adopted Nikon cameras and lenses while shooting the war.

Nippon Kogaku realized the value of these American photojournalists and made sure to offer their full support to them regardless if they used Nippon Kogaku products. Lenses and bodies would be serviced and cleaned with a fast turnaround for no charge, but even more important, the factory would regularly survey the photographers asking what they liked, and didn’t like about them. David Douglas Duncan and Carl Mydans made special trips back to the Nippon Kogaku factory in Shinagawa each time they visited Tokyo, meeting with the company president to give their feedback and that from other photographers whom they encountered. Nippon Kogaku valued all feedback, both good and bad, and was very eager to improve their designs.

By the end of 1950, excitement about Nikon cameras and Nikkor lenses was very high, not just for LIFE photographers, but other news organizations as well. Michael James from the New York Times, John Rich from NBC, and Max Desfor from the Associated Press all got their hands on Nikon equipment and echoed the praise from their LIFE counterparts.

Around this time, a New York Times columnist named Jacob Deschin who wrote a weekly photography column called “Camera View” caught wind of the fervor over Nippon Kogaku products and asked to write a story about them. His article would eventually be published on the December 10, 1950 issue where he proclaimed that the Nikon was the first postwar camera to attract serious attention in America. He told the story of Nippon Kogaku’s discovery and how Nikkor lenses were superior to anything the Germans were making at the time.

By 1951, the message was clear, the Japanese camera industry was born and Nippon Kogaku was in the lead. This had a trickle down effect to other Japanese optics companies too. Soon other Japanese companies like Canon, Minolta (Chiyoda Kogaku), Topcon (Tokyo Kogaku), Nicca (later merged to create Yashica), Konica (Konishiroku), and many others started to have international success with their respective models.

According to an article published in the April 1957 issue of Popular Photography, export sales from the Japanese Camera Industry went from $2.3 million in 1950 to $5.8 million only 2 years later. In just a few short years, Japan went from a curiosity to a leader in both camera and optics design. This success helped other types of Japanese industry too. It’s possible that electronics and automotive companies like Sony, Yamaha, Honda, and Toyota might not have had the success they did, had Nippon Kogaku and the rest of the Japanese camera industry not paved the way.

As Robert said earlier, David Douglas Duncan was a master promoter, and promote he did through word of mouth, through his photography in LIFE magazine, and in 1951, through his book “This is War” which featured hundreds of images all shot using his Nikkor lenses and featuring a prologue proclaiming the Nikkor lenses to be the best in the world at that time.

I asked Robert why Nikkor lenses were better than those made in Germany by Zeiss and Leitz as each of these companies already had considerable experience making great lenses. Robert said that Nippon Kogaku’s manufacturing practices were much more thorough than anything the Germans were doing and that they listened to the critiques of photographers and were very interested in feedback, both good and bad.

- They were able to produce perfect, bubble free glass before the Germans, and each piece of every lens was 100% inspected at every step of the way during the manufacturing process, ensuring that only the best of the best pieces made it out the door.

- When a lens was being constructed, Nippon Kogaku collimated their lenses at a distance of 10 feet compared to Zeiss who did it at infinity. When a lens is collimated for perfect focus at infinity, as you move away from that point, the potential for error increases. By doing it at the 10 foot mark like Nippon Kogaku did, the perfect focus point was at the average distance the lens was most likely being used at.

-

Nippon Kogaku developed lens coatings during World War II that were years ahead of what other companies had. In addition to extreme standards for quality control, Nippon Kogaku was way ahead of the Germans in lens coatings. Nippon Kogaku had been coating their lenses for military use during the war, something the Germans weren’t doing. This not only improved color performance, but also reduced flare and increased sharpness. Zeiss did not get good with lens coatings until around 1950, and Leitz didn’t really perfect it until the Summicrons in 1954 so Nippon Kogaku had nearly a decade head start.

David Douglas Duncan would continue to be a huge advocate for Nippon Kogaku and Nikon throughout the rest of his life. He would eventually switch to the Nikon F SLR and maintain a relationship with the company until his death. In 2017, Nikon celebrated it’s 100th anniversary with a video tribute to Duncan, proclaiming him as the first professional photographer to use and promote Nikkor lenses.

David Douglas Duncan isn’t solely responsible for “discovering” Nikon, as many people were involved, from Jun Miki, Horace Bristol, Carl Mydans, plus the positive press by other photographers, and the promotion of it by Jacob Deschin. Of course the products themselves were probably the biggest advocates for Nippon Kogaku’s positive reception. Still, Duncan is considered by many, even Nikon themselves, to have played the biggest role and one that caused a ripple effect for decades to come, not only on the photographic industry, but in all Japanese manufacturing.

Credits

I could not have typed this article without the help of Robert Rotoloni, but I also took bits and pieces from other sources, including two period articles including a Nikon article from the June 1951 issue of Modern Photography:

And an article called “How the West was Won” which appeared in the March 1991 issue of Popular Photography:

Finally, Nikon’s official website has a special section dedicated to the memory of David Douglas Duncan:

Don’t forget Hans Liholm and the Overseas Finance and Trading Company—the importers of Nikon products from 1949 until 1953. Gasser did work for them.

Thanks for the tip, Wes! I know that there is more information to the story out there, but I had to draw the line somewhere, otherwise my article would turn out to be just as long as both yours and Robert’s book! Next time I see him, I’ll be sure to ask him about Hans and the Overseas Finance and Trading Company.

A valuable addition to this account is ‘Tokyo on a 5 Day Pass’ by Horace Bristol. It tells the same story from his perspective. Bristol also made reference to Canon, and stated that the Canon Serenar f2 85mm lens was the finest of any type he had ever encountered. It would appear from this that both Nikon and Canon were keystones to the success of the early Japanese camera industry. The book is a very interesting read on a fascinating period of photographic history. I have had my copy for years, but the last time I checked, used copies were still available.

Roger, thanks for the book recommendation! I will definitely keep a look out for it and pick it up someday! This period of Nikon’s history is very fascinating to me!