This is an ANSCO Super Regent 35mm folding rangefinder camera, made between the years 1955 and 1959 for ANSCO by AGFA Camera Werk in Munich, Germany. The Super Regent is a rebadged AGFA Super Solinette, but sold by ANSCO in the United States. Both the Super Solinette and Super Regent cameras were replacements for the earlier AGFA/ANSCO Karat/Karomat series. The Super Regent was a mid priced model with a 4-element f/3.5 coated lens, coincident image coupled rangefinder, and a high quality Synchro-Compur shutter.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/3.5 AGFA Solinar coated 4 elements

Focus: 3′ to Infinity

Viewfinder: Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Synchro-Compur Leaf

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: M & X Synchronized PC Port and Cold Shoe

Weight: 533 grams

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/agfa_ansco/ansco_regent_lvs.pdf

History

The company whose name makes up the first 5 letters of the camera’s name, ANSCO, was a subsidiary of a German company called General Aniline & Film Co., or GAF for short. The history of this company is quite long and complicated. If you’d like to know more, there is a really excellent timeline compiled by William L. Camp which can be viewed here. I’ll do my best to provide a summary of ANSCO’s history.

In 1842, a Columbia University graduate named Edward Anthony opened a daguerreotype gallery in New York city called E. Anthony & Co. Anthony sold daguerreotype chemicals and supplies, but eventually started to manufacture his own cases and other accessories. In 1852, he was joined by his brother Henry T. Anthony and the company was renamed E. & H. T. Anthony & Company.

Over the course of the next few decades, the Anthony brothers did very well, growing their business to a point in which they claimed to be the largest photographic chemical and apparatus manufacturer in the world. They made all sorts of camera equipment using all the latest processes. In 1883, the company built the world’s first mass produced instantaneous camera, called the Schmidt Patent Detective Camera.

In 1902, E. & H. T. Anthony & Company would merge with the Scovill Manufacturing Company out of Waterbury, Connecticut who had been in business since 1802. The merged company became the Anthony & Scovil Company, or ANSCO for short and they moved their headquarters to Binghamton, NY. The newly merged company was now the second largest photographic film and camera maker in the United States, right behind the Eastman Kodak Company.

Throughout the first few decades of the 20th century, ANSCO remained a film first company, but in 1924, would release their first camera, the Automatic ANSCO. Four years later in 1928, the company was bought by the German company AGFA (some sources say they merged, but its not 100% clear who was the controlling interest).

After 1928, the two companies operated under the name AGFA-ANSCO and would begin a partnership of releasing nearly identical cameras under both names. Many of the cameras sold in the United States were copies of existing AGFA models, but actually made in the USA.

In the years leading up to World War II, the AGFA-ANSCO business grew rapidly, but in 1941, the US Government would seize assets of the American arm of the company due to its ties with Germany, who was considered an enemy at the time. The US side of the company was merged with the American company GAF (which stands for General Aniline & Film) based out of New Jersey and the company’s operations were overseen by the US Department of Treasury.

The American arm of AGFA-ANSCO-GAF (whatever you want to call them) continued to manufacture film equipment, but stopped camera production in favor of sextants, range finders, and other optical equipment for the war effort. During the war, all products were sold and marketed under the name ANSCO in order to distance themselves from their German ties. After the end of the war, the US Government continued to control the operations of ANSCO as enemy property up until the early 1960s before letting it run as a private company again.

The American arm of AGFA-ANSCO-GAF (whatever you want to call them) continued to manufacture film equipment, but stopped camera production in favor of sextants, range finders, and other optical equipment for the war effort. During the war, all products were sold and marketed under the name ANSCO in order to distance themselves from their German ties. After the end of the war, the US Government continued to control the operations of ANSCO as enemy property up until the early 1960s before letting it run as a private company again.

Meanwhile, over in Germany, AGFA continued operations during the war, most likely to produce equipment for the German side of the war. Once the war was over, the Allies would break up the IG Farben company who owned AGFA and create several small companies. In late 1945, AGFA would reappear as a standalone company in East Germany and they would resume making film and cameras.

In 1945, both ANSCO-GAF and AGFA would resume their partnership selling and making cameras. This partnership would last for several more years, but eventually disintegrate in the 1960s. ANSCO would release 9 new models, 7 of which were based off pre-war cameras, and two would be all new designs. AGFA continued to innovate and released several new models over the next decade. In 1952, AGFA would become AGFA AG and become a wholly owned subsidiary of Bayer.

One of the most popular and long lived cameras that was sold by both AGFA and ANSCO was the Karat/Karomat series. The Karat was a compact 35mm camera that was designed to compete with the Kodak Retina and would use AGFA’s own variant of 35mm film which they called AGFA Rapid film. The film itself was nearly identical to Kodak’s 35mm film, but came in a special metal cassette and would transport from cassette to another cassette. It did not need to be rewound back into the cassette at the end of the roll. Once you reached the end of a roll, you would open the camera and remove both cassettes.

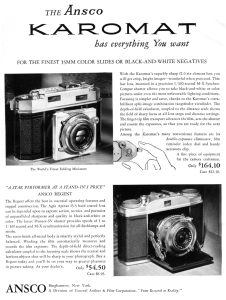

The Karat sold well both before and after the war. Models sold by ANSCO in the United States were called the Karomat, but were otherwise identical. Due to the success of Kodak’s 35mm film format, in 1948, the Karat was adapted to use regular 35mm film in a new model called the Karat 36.

The Karat and Karomat continued to sell well into the 1950s. It was a German rangefinder that had a variety of good to excellent 3, 4, and 6 element lenses, German Compur shutters, and leather bellows. When folded shut, the cameras were very compact and portable.

Although good cameras, the Karat and Karomat were not cheap. In an ad from the February 1954 issue of Modern Photography, the ANSCO Karomat with the Schneider 50/2 lens was listed at $164.10 which when adjusted for inflation is comparable to over $1500 today. Not everyone could afford a camera in that league and with an increasing number of cameras coming out of Japan, it was clear that both AGFA and ANSCO needed a less expensive option.

In 1953, AGFA would release two new, less expensive models called the Silette and Solinette. The Silette was a solid bodied camera with front element focus, a 3-element AGFA Apotar lens, and a Pronto shutter with speeds from 1/25 – 1/200, and the Solinette was a folding bed camera with unit focus, a variety of 3 and 4-element lenses, and better Prontor and Compur shutters with speeds as fast as 1/500. Both the Silette and Solinettes had a rangefinder version both called the Super Silette and Super Solinette.

For export to the US, ANSCO carried their own versions of these 4 cameras called the Memar and Regent. Like the AGFA branded models, there were scale focus and rangefinder versions available in the US with the word “Super” in the name. As best as I can tell, all 4 of the ANSCO models, the Memar ($39.50), Super Memar ($69.50), Regent ($54.50), and Super Regent ($87.50) were all available in late 1953, early 1954 and were available while the Karomat was still in production. Some sources online suggest the Regent replaced the Karomat in ANSCO’s lineup, but that’s not entirely true as I’ve seen all of these models advertised together at the same time.

The Super Regent, being the most advanced of the 4 new models, sold for $87.50 which was still a far cry from the $164.10 price that the Karomat demanded. I saw some information that around 1955, the Karomat’s price dropped to $125 making it a bit more attractive, but still a large jump up from the Super Regent.

The Super Regent was well received and earned praise for what was at the time a new LVS (light value scale) on the shutter. With numbers ranging from 3 to 18, the shutter on the Super Regent was designed to simplify exposure calculation when used with a compatible light meter. You would set your film speed on your handheld meter and whatever number it would suggest, you would set on the shutter, and that would mean that an appropriate shutter and f/stop was selected automatically.

The February 1955 issue of Modern Photography had a 4 page review of the Super Regent and spent extensive time talking about the new LVS on the shutter.

Editor John Wolbarst had a lot of positives to say about the LVS (which he says should actually be called an EVS) suggesting it is an improvement over previous designs. Wolbarst commended the switch to what would become the new standard shutter speed settings of 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 30, 60, 125, 250, and 500 as this allowed for an even spacing of shutter settings where the exposure is always half or double the previous setting. I do not know if the Super Regent was the first with the modern shutter speed numbers, but it had to have been one of the first.

Surprisingly little of the review is about the camera itself, but Modern gave the compact size of the camera, and coupled rangefinder positive marks suggesting that for the features it had, that it was a good bargain at it’s price.

The Regent and Super Regent were in production until at least 1960, at which time it disappeared from advertisements. It likely was a decent seller as it’s price when adjusted for inflation was comparable to about $800 today making it a capable midrange camera. Advanced amateurs who wanted a German made compact rangefinder with a good but not fast 4-element f/3.5 lens likely would have been interested in this model.

Today, there is little demand for AGFA or ANSCO’s midrange models like the Super Regent making for a compelling bargain on the used market. This one came to me in a lot of broken cameras and had I not seen the two windows, indicating it had a rangefinder, I like would not have picked it up at all. If you are looking for an under the radar camera, there is a lot to like with the Super Regent. The f/3.5 Apotar lens is a quality 4-element design that is probably Tessar based and it comes with the same German Compur shutter that likely would have appeared in more desirable cameras like the Kodak Retina, and it’s compact and folding body makes for an extremely portable camera.

Repairs

The Super Regent came to me with a variety of issues. It was sold in “AS/IS” untested operation, but I was prepared for typical conditional things like possibly a stuck shutter and ANSCO’s famous “Green Goo” grease that renders things like the focus wheel inoperable.

Upon receipt of the camera, I was right, the viewfinder was cloudy (although not terrible), the shutter was seized, and the focus ring was completely stuck. I was not prepared for the Swiss cheese bellows on the side of the camera, however. Kodak folding cameras from the 1950s are notorious for having shredded bellows, but not ANSCO folders, and certainly not ones based off German AGFA designs. I thought that perhaps if I could get the shutter and everything else working, this camera might be worth patching the bellows, so I got to work on fixing it.

Sadly, I did not take any photos of the repair, but it was quite simple. The front lens element screws off by hand and beneath it is a rather ordinary Compur shutter. I talk about flushing Compur shutters in my article “Breathing New Life into Old Cameras” so you can check out that thread for general instructions. Normally, I recommend removing a shutter from a camera before flushing it, but the rather low value of the Super Regent, and the fact that it was in such terrible shape to begin with, I did the whole process with it still mounted to the camera. In terms of the focus, a liberal dousing of naphtha was all that it needed to free up.

The bellows were beyond any simple pinhole repair. This camera needs new bellows to properly work as it is clear that at some point in time, the bellows got pinched in the door hinge which is part of the folding mechanism. It doesn’t look like it was abused but obviously it happened and desperate times call for desperate measures so they say and in this case, I decided to pour…literally POUR liquid electric tape inside of the open bellows into the areas where the bellows were torn. I used a Q-tip to spread the liquid around and let it dry over night.

It actually took a couple of applications of the liquid electric tape to cover all of the holes, but once I saw that it was light tight, the liquid electric tape was on so thick, there was no way this camera would fold properly again. Realizing how unlikely this camera ever is to be used in the way it was intended, I made the decision to load it film and leave it open the entire time without ever folding it as that would surely crack or in someway tear the bellows even worse than they already were.

My Thoughts

The ANSCO Super Regent is a fascinating little camera with a feature set thats rather uncommon. Aside from the Kodak Retina series, and the previously mentioned AGFA/ANSCO Karat/Karomat there weren’t many folding 35mm cameras with a decent lens and a rangefinder. Typical compact folding cameras were either of the inexpensive medium format variety, or in the case of 35mm rangefinders, were generally solid bodied cameras. I have to wonder if people who were willing to pay for premium features didn’t trust folding cameras due to the perceived weaknesses of a bellows. It didn’t seem to hurt Retina sales, so why weren’t there more cameras like the Super Regent?

I honestly don’t know, but whatever the reason, there was enough interest for this camera to be built and for that, I am thankful as this is really a wonderful little camera that I am happy to have in my collection. Sadly, it came to be with a list of issues, most significantly of which was the rotted bellows that I talked about in the previous section.

The camera is light weight, weighing 533 grams. This compares to Kodak Retina IIa at 618 grams and an AGFA Karat 36 at 663 grams. When folded shut, the camera won’t quite fit in a front shirt pocket, but easily fits into a medium sized coat pocket or small handbag.

When it comes to folding cameras, I tend to prefer bottom hinged doors where the door folds forward, as opposed to the Kodak Retina’s design with the side hinged door. For one, the symmetrical design is more visually appealing, but it makes it easier to access the controls on the lens from both sides. I find the door position on the Retina to be a bit counter intuitive in some situations.

The top plate of the camera features both the rewind and wind knobs. As was typical of early 1950s cameras, the Super Regent pre-dates a wind lever but the large diameter of the knob makes for quick action when advancing the film. I did not feel as though the lack of a wind lever significantly slowed me down while shooting.

Opening the camera isn’t at first obvious as the door release is not on top of the camera where you’d expect to find it. Instead, it’s a little button on the camera’s left side, beneath the rewind knob. Pressing this button will unlock the door and it will open part way. You’ll have to help it the rest of the way. For when it’s time to close the door, you put equal pressure on the “elbows” of both hinges on either side of the shutter, to collapse the front. The instruction manual doesn’t specifically say this, but on mine, I had to also press down the door release on the side of the camera while folding it shut for it to latch. This may not be normal behavior though.

The viewfinder is typically small of the era, but offers a decently bright and easy to see circular rangefinder patch. It was refreshing to see a coincident image rangefinder in this camera which was designed to be a lower cost alternative to the Karat which only got the rangefinder patch with the Karat IV model a few years earlier. I am not sure if the rangefinder design is the same, but based on how it looks from the outside, it very well could be the same system from the Karat IV.

To the right of the viewfinder are both a locking lever that releases the lock for the button farther to the right. This button acts as both the rewind release for when you’ve reached the end of a roll of film, and also as a way to reset the exposure counter when loading in new film. You must always release the lock via the sliding lever with the arrow on it. Each press of the rewind release button increments the exposure counter so you may reset it to ‘1’.

Loading film into the Super Recent is pleasantly uneventful, especially for a mid 1950s camera where many models often had quirks. A new cassette goes on the left, the film leader stretches across the film plane and attaches to a fixed take up spool on the right. Unlike the Karat/Karomats, there is no flap that must be lifted up to properly thread the leader.

The front of the camera is dominated by the Synchro Compur shutter and lens. Although suggesting it’s a more advanced model with it’s fancy “LVS” numbers, the shutter works like any other Compur shutter.

The Super Regent has double image prevention by locking the shutter release after advancing the film, however, it is not a self-cocking design. There is a cocking lever on the shutter that must be set before each image is taken. Shutter speeds are changed via the ring around the perimeter, and f/stops are changed via the diapragm setting letter on top of the shutter. Since the Super Regent employs a LVS scale, shutter speeds and f/stops are coupled together. The red numbers along the bottom of the shutter ring show the LVS numbers, and will make corresponding changes to the shutter speed as you select a different f/stop. To interupt the system and choose your own combination of shutter speed and f/stops, you must manually move the triangular pointer on the bottom of the camera.

This system is very similar to the one that Kodak AG uses on the 1950s Retinas in that there is no easy way to pick your own shutter speed and f/stop combination without having to fiddle with this little pointer. Rather than continue to complain as I’ve done in previous reviews, I’ll just say that although I am not of fan of it’s implementation, I understand why this was done back when this camera was a current model.

Finally, to adjust focus, you turn the large knurled ring around the back of the shutter. Under normal circumstances, this ring is easy to turn and makes corresponding changes to the rangefinder, however due to the lubricant used on these cameras when they were new, they can become quite stiff with age. If your focus ring is difficult to rotate, don’t force it as you could damage something else. It will need to be cleaned.

My Results

I had some very serious concerns about the usability of this camera with my repairs to the shutter and bellows, and not wanting to waste a whole roll of film in a camera of questionable functionality, I split a 36 exposure roll of Fuji 200 film in the Super Regent with another camera. I shot this film in late February/early March 2018 and developed it myself using a C41 kit purchased from the Film Photography Project.

The results I got from this camera were a mixed bag. It turns out that the Super Regent had another problem that did not reveal itself until after developing the film, which was a film transport issue that would advance the film nearly 2 full frames before stopping for the next exposure. Although the exposure on the counter seemed to be working correctly, in reality, the film was traveling much farther than it should. This meant that when I thought I was at the halfway point of the 36 exposure roll, I was really near the end. I rewound the film into the cassette, transferred it into another camera, and advanced it to the 19th frame and shot 18 more exposures in that camera. Of course, that means that every single one of those images was double exposed with the second half of the ones shot in the Super Regent. The image to the right shows the frame spacing of the film as it was drying.

This left me with about 9 exposures that weren’t double exposed and sadly, many of them were overexposed, or generally not very interesting shots. The gallery above shows the 6 best images I got, and although they’re still a bit bright, I can at least see that the 4-element Solinar lens delivers sharp images with even coverage throughout the frame. I did not notice any significant light or sharpness fall off near the corners, suggesting that this would have been a very capable and compact 35mm camera.

The colors seem washed out too, which I blame on the over exposure, and possibly even the film which wasn’t fresh. Regardless of the reason, I am sure the washed out colors were not indicative of what this camera was capable of new.

Since this is a relatively uncommon camera, and it had some severe condition problems, and a completely rotted out bellows, this is likely the best results I’ll ever get out of this particular model. While I generally liked the camera, there’s really nothing special enough about it that would compel me to seek out a better example.

It’s always difficult to write reviews on cameras that don’t perform like you expect. I don’t want to unfairly criticize this camera as I am positive that when new, it would have delivered better results than I got. This is just an important reality when it comes to collecting and shooting 60+ year old cameras. When the designers and engineers were creating this particular Super Regent, I doubt any of them expected someone would be using them 63 years later and writing reviews on something called the Internet!

I am still impressed that I don’t have failures like this more often, but even when I do, I can’t really be that disappointed. This is a neat camera with a handsome symmetrical design, that despite it’s conditional issues, looks quite nice sitting on a shelf. I don’t normally like to hold onto cameras that don’t work, but sometimes I make exceptions, and this is one of those times.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The ANSCO Super Regent was a twin to the AGFA Super Solinette and was a lower cost alternative to the Karat/Karomat rangefinder made by both companies. It uses a more traditional bottom hinded folding cover, and has an easy to use coincident image rangefinder. The shutter is a modified Compur leaf shutter with a coupled LVS feature that was pretty neat when it first came out, but is a bit of a chore to use today. The 4-lement f/3.5 lens isn’t as impressive sounding as the Schneider lenses often found on the Karat/Karomat, but it’s no slouch either. In working condition, this is a nice camera with styling cues very typical of a mid 1950s 35mm rangefinder. This example was in poor condition with rotted out bellows, so it took quite a bit of effort to use, and even after that, still produced questionable results. I’ll acknowledge that in better condition, this is probably a pretty capable camera, but I suspect that anyone else looking for this model will run into some or all of the same issues I had. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.8 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Ansco_Super_Regent

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/index-frameset.html?AnscoSuperRegent.html~mainFrame

https://camerashiz.wordpress.com/ansco-super-regent/

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/back-in-action-super-regent.157334/

I think the pictures you posted are quite nice!

Definitely, an honest review with all the hiccups of an aged camera. It’s sad that the bellows and helical grease did not age well.

Just a heads up from someone that still has one rebranded Ansco, in addition to three Agfa folding cameras. All of them were projects to get in working order – two of which by the way required replacement bellows. On a 60 year old camera I always plan on having to tune up the leaf shutters on old folders as well. The latter is a service issue that goes with the territory, even on better spec’d Voigtlanders and Zeiss-Ikons.

While the build quality may not be up to Voigtlander or Zeiss Ikon specs, the images from Agfa folders have surprised me once I had them in good working condition. The Super Solinette and Super Regents were the 35mm counterparts to the medium format Super Isolette / Super Speedex models in the Agfa folder line up.

I did have a go with unit-focusing 50/3.5 Solinar on a Super Regent about 15 years ago. In my opinion, the Solinar out performed my 50/3.5 Elmar from the period with color film.

I have two of these cameras, and they both came to me with frozen focus helicols, sticky shutters and were generally dirty from being in storage for years, but neither had bad bellows. It must have been your bad luck to find one so abused!

I write to let you know one of my cameras has the same spacing issues, but I think I have traced it down to insufficient hold-back tension on the supply spool. It appears that the film will “hop” over the sprocket teeth of the geared shaft that establishes proper frame spacing if there is not enough hold-back tension. This repeats in a fairly regular fashion with a dummy roll, so it might have to do with both tension and how I wind the film; how many “twists” I do to advance the film. Humans tend to do repetitive tasks in a uniform fashion, so this could be a clue too…

In any event, I find that if I apply a small amount of drag on the supply side spool via the rewind knob as I advance the film, it tends to count properly and not skip perfs.

Now, why one camera does this and the other does not is a bit of a mystery, as they appear to have about the same amount of friction on the rewind spool, but I am starting to wonder if the pressure plate tension is a factor here as well. Perhaps a combination of hold-back tension AND a weaker pressure plate spring will allow our more modern, thinner film stock to skip over the tiny diameter sprocket shaft, whereas the thicker, stiffer film stocks of the past would not have this problem.

Regardless, I really enjoy your camera reviews and your website in total!

Keep up the good work!

Frank

Great info Frank! Your explanation for why I had so much space between my exposures very well could be correct. As much as I liked the camera, between the film advance, stiff focus, and torn bellows, I ended up getting rid of a camera in a “junk camera purge” a few months back. Since then, I’ve come across a REALLY nice ANSCO Super Memar with a Solagon, which isn’t exactly the same camera, but similar enough. I one day hope to review that.