The horror genre is known for movie franchises with many sequels, remakes, and reboots. In the 70s, 80s, and 90s, original horror movies would often spawn a whole series of sequels, mostly upping the ante on the thrills, spills, and chills of the original. Sometimes the sequels continued the story of the first film, sometimes they didn’t. Most sequels never matched the quality and originality of the original, but on occasion they came close (A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), but on others, they laughably miss the mark by a wide margin (A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge).

The horror genre is known for movie franchises with many sequels, remakes, and reboots. In the 70s, 80s, and 90s, original horror movies would often spawn a whole series of sequels, mostly upping the ante on the thrills, spills, and chills of the original. Sometimes the sequels continued the story of the first film, sometimes they didn’t. Most sequels never matched the quality and originality of the original, but on occasion they came close (A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), but on others, they laughably miss the mark by a wide margin (A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge).

Sequels by their very nature usually lack creativity as they build upon established plot elements and characters from the first film, but that never stopped people from making them. Usually sequels were made with a lower budget and would make just enough money to keep making more. But by the start of the 21st century, the Hollywood sequel machine slowed to a halt and something new, and even more frightening happened.

The Reboot.

A reboot is not the same thing as a remake. Where a remake is an attempt to retell the same exact story as the original but in a modern way with new actors, a reboot starts off like a remake of an existing story, but goes in it’s own direction. They’re sort of like a sequel and a remake combined together. By starting the story over, a new director and cast can revisit a story we’re already familiar with but still have some creative freedom to turn it into their own story.

It’s that creative freedom that often spells doom for most reboots. A reboot is usually only done to a movie that was once successful, and it can be very difficult to take a successful story that probably already has a lot of fans, and reinvent, or reboot the story. Not all reboots are bad, however. In fact, a few have been quite good. The 2004 reboot of Dawn of the Dead did a good job of capturing the potential fun of being trapped in a mall during a zombie apocalypse while introducing new characters and ways to kill them off. The 2013 reboot of The Evil Dead somehow managed to take one of the best horror movies of all time, and do it justice by overwhelming us with sheer gore while trapping a cast of willing 20-somethings in a familiar cabin-in-the-woods setting. I’ll even go on a limb and say I quite liked Rob Zombie’s 2007 take on Halloween. He somehow managed to “Rob Zombie-ify” the original John Carpenter classic while staying true to the original Michael Myers story line and keeping in step with his unique film making style.

Most reboots however, are quite bad. Usually ranking somewhere from “meh” to downright unwatchable the reboots of A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, The Wicker Man, Poltergeist, House of Wax, Amityville Horror, Carrie, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and many, many, more were all unnecessary attempts at recapturing the glory of a well done original. If a reboot is intended to start a story over again, I would think that for it to be successful it should spawn some sequels of it’s own, continuing on the direction of the reboot. In the above list of movies, only Halloween managed to do that with Rob Zombies reboot-sequel, Halloween II. Otherwise, its very rare for a reboot to go off in it’s own direction and spawn it’s own sequels.

What do reboots have to do with cameras? Not much really. None of the cameras I’m about to talk about here are reboots of a previous model. I guess the reason I chose this theme for my 4th installment of the “Cameras of the Dead” series is because I am running out of ideas for a horror movie theme, so I chose one that lacked originality…like reboots do!

So here we are, just in time for Halloween, three more cameras that for one reason or another, I was unable (or unwilling) to shoot, but I thought they were interesting enough to review.

Kodak No. 3A Folding Brownie (1909)

This is a Kodak No. 3A Folding Brownie made by the Eastman Kodak Company from 1909 to 1915. The No. 3A version of this camera took very large “postcard” sized images on 122 format film. There was a slightly smaller variant of this camera known as the No. 3 Folding Brownie that took smaller images on 124 film. The Folding Brownie series were Kodaks least expensive folding roll film cameras designed to make large contact prints using inexpensive film. Although built used wood and cardboard bodies, the cameras were generally pretty durable and able to withstand quite a bit of use.

Film Type: 122 Roll Film (six 5 ½” x 3 ¼” exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown Focal Length Meniscus Achromat Uncoated single-element

Focus: 6 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Reflecting Watson Type Finder

Shutter: FPK Automatic Metal Blade

Speeds: T, B, I

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_brownie_folding_3_3a.pdf

My Thoughts

This No.3A Folding Brownie is likely the oldest camera in my collection, being made between the years of 1909 and 1915. As best as I can tell, at some point in it’s production, Kodak switched from red to black bellows suggesting mine is an earlier variant. It is usually pretty difficult to narrow down the exact years of production of these old Kodaks, so as a general rule I just consider them to be made in the first year I knew that model existed.

This camera came to me via Facebook, and I was alerted to it by my wife (who regularly chides me for my collection). The lady selling it was asking $200 and I politely PMed her and asked how she came to that price and she said she just made one up, without any basis for it’s worth. I ended up talking her down to $20 and met her on my lunch break one day in a McDonald’s parking lot and picked it up.

The Folding Brownie was in excellent condition when I first opened it. Other than a surface layer of dust, the camera was completely in tact, with what looked to be light tight bellows. The leather handle on top of the camera was not only still attached to the camera, but it showed no signs of cracks or tears, something you rarely see on early 20th century box and folding cameras. The shutter was left open in “T” mode, so I released it from it’s (likely) decades long prison and tested the Instant mode, to which the camera responded as it should. I should point out that many of these earlier Kodaks had a lens design in which the glass lens element is behind the shutter. Looking at the front of the camera, someone not familiar with it’s design might think the lens is missing, when in reality the lens is behind the shutter. This is actually a good thing as the shutter acts as a built in lens cap, protecting the glass elements from dust and debris.

I declared this one a winner, mostly. While the camera seemed to be in perfect working order, this is a No.3A which means it uses type 122 roll film which was one of the largest types of roll film ever made. Each exposed image is nearly half a foot wide. Take a look at the image to the left where I show a 122 spool next to a (still very large) 116 spool and 120 spool. Back when cameras like this were made, photography was still an expensive industry. Models like the Folding Brownie might have been affordable by the mid to lower class, but developing the film cost money. Even after developing the film, you still needed a way to make prints from your exposed negatives which typically involves some type of enlarger to make images big enough to be framed.

I declared this one a winner, mostly. While the camera seemed to be in perfect working order, this is a No.3A which means it uses type 122 roll film which was one of the largest types of roll film ever made. Each exposed image is nearly half a foot wide. Take a look at the image to the left where I show a 122 spool next to a (still very large) 116 spool and 120 spool. Back when cameras like this were made, photography was still an expensive industry. Models like the Folding Brownie might have been affordable by the mid to lower class, but developing the film cost money. Even after developing the film, you still needed a way to make prints from your exposed negatives which typically involves some type of enlarger to make images big enough to be framed.

As an alternative to enlarging film, “postcard” cameras like this Folding Brownie became popular that took images that were already about the size of a post card and didn’t need to be enlargened. When film was developed, the end result would be created via something called a contact print. A contact print is basically when you take an exposed negative and put it in contact with light sensitive paper and momentarily shine light through the film to “print” a positive image on the photographic paper. Of course, this still needs to be done in a darkroom with chemicals to stabilize the light sensitive paper, but the benefit is that large complex equipment like an enlarger was not necessary.

When you would shoot images in a camera like this, you would send out your film to be developed (or do it yourself) and then take your exposed film and make positive prints directly from the negatives that were the same exact size. If you were ever in an antique shop and saw an old photo album that had photographs that measured 5 ½” x 3 ¼”, it is very possible they were shot using a 122 film camera like this one.

The Folding Brownie is a pretty neat camera. When folded, it resembles a medium sized box. To someone not familiar with old cameras, they likely would have no idea that this was even a camera. To open the front, a hidden button on the top of the camera right in front of the handle must be pressed to unlock the door. This is not a self-erecting design, which means that once the door is opened, you must manually pull out the lens and shutter by gripping the shiny metal handle immediately below the lens.

Unlike other folding Kodaks in my collection, the Brownie has click-stops at various focusing distances which means the camera will lock in at one of 8 focusing distances from 6 feet to 100 feet (infinity). While this may seem limiting today, the reality is that these cameras never needed precise focus to begin with, so each of the set distances on the focusing plate are more than enough to cover any distance. This is especially convenient today, as many of the earlier folding cameras I’ve encountered struggled to stay at their proper focusing distances. Over time, things loosen up, but that wouldn’t be a problem with this camera as once the camera is set to a specific distance, you must press down on the locking lever to move it to another distance.

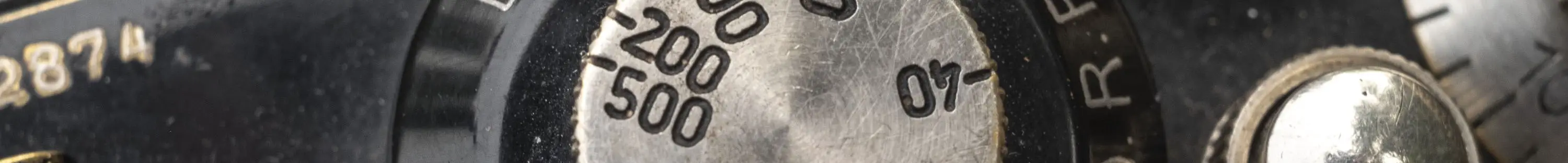

All of the camera’s controls are on the shutter itself. At the 12 o’clock position is the shutter speed selector. You only have three choices here, T (for Time), B (for Bulb), and I (for Instant which is approximately 1/25th second). At the 6 o’clock position is the aperture selector, which gives you values from 8 to 128.

If the thought of an aperture of f/128 sounds strange, you should know that prior to the 1920s, Kodak used a different system for calculating f/stops known as the US System or “Uniform Standard” (also sometimes incorrectly called the Universal System), which was originally developed by the Photographic Society of Great Britain in the 1880s. Using this system, the Folding Brownie’s maximum and minimum apertures of 8 and 128 are actually closer to f/11 and f/45 using the modern system we use today.

Finally, the last thing on the shutter is the shutter release which is near the 11 o’clock position. The shutter release on this camera is not threaded for a cable, and there is no self timer. At the 9’clock position is a chrome cylinder which acts as a dampener for the shutter. This cylinder is filled with air and has a small piston in it to delay the closing of the shutter. These cylinders are more common on variable speed shutters like the Wollensak Optimo, but was incorporated into other designs like the one here.

Considering the excellent condition of this 100+ year old camera, I really wanted to try and shoot some images through it, but a combination of the sheer size of 122 film, and the fact that the camera only came with one spool meant I would have had to either get really creative and insert single sheets of 4×5 film in the camera and figure out a way how to protect it and develop it, or fab up some type of 120 to 122 adapter and shoot some super panoramic 5 ½” x 2 ¼” on 120 film. I decided to just admire the camera for it’s beauty and talk about it here in my Cameras of the Dead series. While the camera itself is still very much alive, it’s film format has long gone the way of the dinosaur and prices for expired 122 film in eBay are in the $40+ and up range. Wikipedia suggests that 122 film went out of production in 1971 so my options would be extremely limited for viable original film.

Ising Puck (1948)

This is an Ising Puck, a compact and elegantly designed half-frame 127 roll film camera that was made between the years of 1948 and 1950. The Puck has a collapsible lens tube and is often found with Prontor or Compur shutters with mid-level lenses by Steinheil München, Staeble Kata, or Rodenstock suggesting it was probably a mid-range model, but I can’t really be sure of much more than that.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (sixteen 3cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 5cm f/2.9 Steinheil München Cassar coated 3-elements

Focus: 0.9m to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Optical Finder

Shutter: Compur-Rapid Leaf on a Collapsible Tube

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: Coldshoe and FP Flash Sync

Manual: None

My Thoughts

The Ising Puck is one of the most mysterious cameras in my collection as it was made by a company that I found almost no information on. Even short lived companies like Clarus, Detrola, or Aires have more complete histories on the Internet. Very little is known about the Ising Camera Company other than it was founded by a man named Eugen Ising in Bergneustadt, Germany. The Ising company may have originally started out making photographic accessories such as tripods in the 1920s, but that is about all I could find online. If you search Google enough, a fair number if Ising tripods will show up. Ising also made a small number of other cameras like the Isis and Pucky, but the company seemed to disappear around 1954.

Towards the end of the company’s existence, Ising must have developed some sort of relationship with an American distributor as one of their models, the Ising Pucky, was rebadged and sold as the Bolsey Bolseyflex, and the Sears Tower 120 Flash. The image to the right shows all three variants side by side.

Beyond this, there is nearly no other information of the Ising company, their origins, and what became of them. The Puck was likely the company’s highest end model as their other known models were very basic and likely sold for very little. By the 1950s, the dominance of the German camera industry was being superceded by Japan, so it’s plausible that the market simply dried up. The company’s headquarters in Bergneustadt was located in what was then West Germany, and it is likely that the weak post-war Germany economy contributed to it’s demise.

I had never heard of the Puck or even the Ising company for that matter before spotting this camera in an antique shop sitting in a leather case with the name AGFA embossed on it. The little tag accompanying the camera called it an AGFA Puck, and quick research on my phone didn’t turn anything up, so I brought the camera home for the low, low price of $10. It was not until later that I realized the true identity of the camera.

The Puck was very dirty and in poor cosmetic condition with several strips of body covering missing from the top and bottom of the camera. The main parts of the body were peeling badly. The good news was that the Compur shutter was in working order, even down to 1 second, so that suggested I likely could have shot some film in it.

Of the three cameras featured in this edition of Cameras of the Dead, the Puck is the only one I could have somewhat easily shot, since 127 film is available. It had been sitting in a box of junk for over a year before stumbling upon it and in that time, the desire never came over me to bother putting any film it, so I figured I would just feature it here. Knowing the reputation of Steinheil München Cassar triplets and Compur shutters, I could likely predict that any images shot through the Puck would have looked pretty good. At least as good as those shot with the Foth Derby, which was another capable German built half frame camera that used 127 film.

The in-body optical viewfinder and collapsible lens tube helps keep the camera quite small. When placed side by side with an Olympus XA2, the main part of the body is almost exactly the same width, but the Puck is about a quart of an inch taller. Back to front, the Olympus is still narrower, even with the Puck’s lens in the collapsed position.

All of the camera’s controls are on the shutter itself, so there is no top plate shutter release, or any type of coupled double exposure prevention. You must remember to advance your film after each shot and cock the shutter before taking the next one. The viewfinder is extremely tiny and is not parallax corrected, so you’d need to adjust your compositions when focusing on things close to the camera.

Film loads in the back of the camera from right to left, and you must use both red windows on the back to properly space each half frame of 127 film. Like most half frame 127 cameras like the previously mentioned Foth Derby and Kodak Vollenda, you must use each window twice since 127 film only had exposure markings for “full frame” 8 exposure cameras.

Although there is an accessory shoe on top of the camera, I see no other provision for flash, not even on the shutter itself. This shoe was likely used for accessory rangefinders or light meters, rather than for flash photography. Next to the accessory shoe is an uncoupled depth of field calculator. This calculator looks very similar to the ones Kodak AG would have used on many of their folding cameras of the era. The only other notable feature of the camera is the fold out kickstand on the bottom of the camera that helps support the camera when sitting on a flat surface with the lens extended.

The Ising Puck is an all metal camera that predates the widespread use of plastics in inexpensive cameras, and without film loaded weighs 367 grams. The build quality of the camera is quite good, and the inclusion of the Compur Rapid shutter and decent triplet lens suggests this camera probably competed with cameras like the Wirgin Edinex or possibly even entry level Kodak Retinas.

Considering the huge variety of cameras available when this model was being sold, I don’t know why anyone would have chosen the Puck, or even how many were built. The lack of many available on the used market and the fact that the company came and went so quickly suggests few did.

In any case, the Ising Puck is a pretty neat little camera that looks a little different from other cameras made in the late 40s and early 50s. Mine is in pretty rough condition, but I would bet that an example in nicer shape would be an excellent addition to any collection. Had I chosen to shoot some film in this camera, my guess is I would have likely been happy with the results.

Edit 6/15/19: Fellow collector and good friend of mine, Dan Arnold recently told me about an Ising Puck he had acquired and was shooting some film through. Dan shot two rolls of film, an expired roll of Efke Black and White 127 film, and some bulk 46mm Fujifilm Pro160S film that Dan cut and spooled to 127.

Here is a gallery of Dan’s Puck along with a couple of his sample pics. I must say, that after seeing these, I both need to look into some bulk 46mm color film, but that I should also dig out my Puck from whatever crypt it resides in my basement, and see if I can revive it!

Univex Cine “8” Model A8 (1936)

This is a Univex Cine “8” Model A8 made by the Universal Camera Corporation in New York City, NY starting in 1936. The Univex Cine “8” represented an entire series of inexpensive 8mm cinema cameras that were sold starting in 1936 and lasted until the company’s demise in the early 1950s. There were at least 8, possibly 9 models in the Cine “8” family all with names starting with the A8, lasting to the H8 with each model getting more advanced. The Cine “8” was a very successful camera and it’s $9.99 starting price helped it to bring motion picture photography to middle and lower class families who otherwise wouldn’t have been able to afford it.

Film Type: 1x8mm single perforated Universal cinema film on 30′ spools

Lens: Unknown Focal Length f/5.6 Ilex Univar uncoated unknown elements

Lens Mount: Univex Screw Mount

Focus: Fixed Focus

Viewfinder: Flip up Metal Frame

Shutter: 16 fps Universal Shutter

Drive: Spring Wound up to 1 minute @ 16 fps

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/Cine8Manual.pdf

History

Of the three cameras in this Cameras of the Dead series, the Univex Cine “8” was the one that was sold for the longest time and in the greatest numbers. Going on sale in 1936 for the low price of $9.95, the Cine “8” was the least expensive motion picture camera money could buy. Using Universal’s own single sprocket Type 100 8mm film that cost 60 cents a roll, the Cine “8” was an incredible value.

The model A8 being reviewed here was the entry level in the Cine “8” series that consisted of models A8, B8, C8, etc, all the way to the H8 which may or may not have gone in sale in 1951. All cameras in the series have an interchangeable screw lens mount with a variety of lenses available. The most common lens was the f/5.6 Ilex lens featured here, but there were several available with specs ranging from f/3.5 to a Wollensak designed f/1.9. Finding a Cine “8” with the f/1.9 lens is quite difficult as very few were made. With a list price of $47.25, the f/1.9 lens put the camera well out of the price range of the economical buyer that would have been interested in the first place.

Each of the following models had their own unique names such as the B8 Trueview Cine, the C8 Exposition and Turret Cine, the D8 and E8 Cinemaster Standards and Specials, and finally the F8 Cinemaster Jewel. According to Cynthia Repinski’s incredibly detailed book “The Univex Story”, in 1951 a model H8 Cinemaster was developed, but it possibly never went on sale as her book doesn’t list a price and considers it to be extremely rare. Universal was on the verge of bankruptcy in 1951, so it’s very possible the model was only developed in pre-production form and never put on sale to the public.

According to the ads featured below from the April 1938 issue of Popular Photography, over 200,000 Cine “8”s were made. It is not clear whether these were all A8s, but considering the model had only been on sale for 2 years at that point, the final production numbers were likely much higher. The A8 is the easiest model to find today, largely due to the high number sold. The second most common model was the C8 which was a step up from the B8 (which itself was an A8 with an optical viewfinder in place of the flip up one on the A8) which outsold the B8 due to the prices being so similar between the two. For a modest price increase of $2.50, customers could buy the Model C8 which had a self locking hinged cover, an improved governor that allowed the camera to be wound longer than 1 minute, and an improved shutter that would automatically close after each take to prevent blank frames that wasted film. The Model C8 was heavily promoted at the 1939 World’s Fair in New York, and as a result was given the nickname the “Exposition Cine”.

The Cine “8” was very successful due in large part to it’s build quality and low price, but it wasn’t sold only as a family camera. Some budding filmmakers also used them in their early years to make some of their first movies. One such filmmaker was Russ Meyer who was known for his “sexploitation” movies in the 1960s and 70s. According to Meyer’s biography “Big Bosoms and Square Jaws” by Jimmy McDonough, when he was 14 year old, Meyer’s mother Lydia pawned her wedding ring to buy him a used Cine “8” camera which inspired him to get into film making.

To go with the Cine “8”s unique 8mm film stock, the company also produced it’s own projectors. The most common model was the Univex P8 which was designed specifically for Univex’s format, but also supported 8mm made by other companies. A variety of short motion pictures were commercially available on Univex film. Most of these were Mickey Mouse and Popeye cartoons.

The Cine “8” series was in production for nearly 15 years and was the company’s most successful model up until it filed for bankruptcy in 1952. A combination of mismanagement and low-profit models contributed to the Universal Camera Corp’s demise. During it’s reign though, the Cine “8” was one of the most popular motion picture cameras in the United States and many were exported to other countries as well.

Today, the Cine “8” is popular among collectors due to it’s beautiful art-deco design, it’s compactness, and overall “cool” factor. Many of these were made, and as a result many are still available on the used market. You can easily pick these up for very little, and although it would be quite difficult to find compatible film to use them in, they were built well enough that most still work.

My Thoughts

I never intended to add an 8mm camera to my collection. Even with my smartphone, I rarely shoot videos as I prefer still photography. Even if I was curious about it, I likely would have started with something that I can more easily get film for. During my research for this article, I found a few random posts in forums from people suggesting that 1x8mm film can be made by slitting regular 8mm film down the middle and then rolling it on Univex spools. This seems like a bit of an undertaking just to find out if the camera works.

I spotted this camera in an antique shop over a year ago sitting on a shelf and although I was aware of the Univex Cine “8” before spying it on the shelf, I had no idea that it would be so small. My initial disinterest quickly changed upon handling this camera. The Cine “8” is very small, slightly shorter than a can of beer. I was impressed with it’s heft and compact size. In addition, it was in it’s original box with the user manual inside, so I figured what the hell and picked it up.

This is a pretty basic camera. Despite its size and beauty, there’s not much else here. The f/5.6 Ilex lens does have an iris which allows you to adjust the aperture down to f/16, but beyond that, there’s no other settings on the camera. The shutter operates at a fixed speed shooting 16 frames per second, and the camera is a focus free design, so there’s not even any kind of focus control. The only touch points to the camera are the unlock for the film compartment, the large winding key, and the shutter button.

The camera has a satisfying resistance while winding it, not unlike a mechanical music box. The original user manual says that you can wind the camera for as much as 1 minute worth of film, but recommends limiting scenes to no more than 30 seconds each. This is likely due to inconsistent speeds as the clockwork motor winds down.

Pressing the shutter release will simultaneously activate the shutter and start advancing the film. Since I had no film in the camera, I was able to watch the shutter operate. It uses a straight metal leaf, not unlike a guillotine and it goes up and down very quickly creating a very cool mechanical click, click, click sound as the camera unwinds. I realize that people don’t normally buy a camera for the sounds it makes, but this thing sounds cool as it runs. Watch the video I made of the Cine “8” being wound and then the shutter running.

There is a footage indicator behind an orange window which measures feet of film left to give you an idea of how many feet of film are left in the camera. A full roll of film is 30 feet long and the camera discharges at rate of 1 foot every 5 seconds. This means that a full 30 foot roll of film is good for 150 seconds or two and a half minutes of film.

Opening the camera requires twisting a manual release lever on the side of the camera opposite of the wind lever. This would later be replaced by an automatic design on the Model C8, but once the cameras are open, they’re all mostly the same.

Here we can see where the supply (top) and takeup (bottom) spools go. Although I didn’t have any film to practice loading in the camera, it seems pretty straightforward. There is a spring loaded pressure plate that must be pulled back and film threaded in between it and the opening for the shutter. It’s hard to see in my image to the right, but on the edge of the pressure plate is a little ‘finger’ that functions like a sprocket in a 35mm camera that helps advance the film when it is running. Pages 6 through 8 of the user’s manual explain the film loading process with pictures in pretty good detail.

Once a new roll of film is installed into the camera, the next step is to manually reset the footage indicator to 0 and then wind the camera and let it run until the letter “S” appears in the orange window. This allows you to move past the film spool’s paper leader and get to where the actual film is. Once you see the letter “S” in the footage indicator, you are ready to start filming.

The model A8 has a flip up metal frame on top of the camera that functions as a rudimentary viewfinder. At the time the A8 was sold, an accessory “telescopic viewfinder” was available which clamped onto the lens of the camera and allowed you to look through a top mounted viewfinder tube to frame your image. Since this camera cannot focus closely, parallax correction is unnecessary. The model B8 came with the top mounted telescopic viewfinder as standard and every model after that featured a through the body optical viewfinder.

Beyond that, that’s all there is to using the Cine “8”. The design was simple, but effective, and it allowed hundreds of thousands of people all over the world to shoot motion pictures of their families, celebrations, and even make rudimentary feature films who wouldn’t otherwise have been able to afford to do so. Had this been a traditional review and I was scoring the camera, I would have awarded the Univex Cine “8” bonus points as a historically significant camera.

As it is though, this is a display piece, a very nice display piece I should add, but one that will likely have the same fate as nearly every other Cine “8” out there. The hobbyist market for people who still use these old 8mm cameras is almost non-existent. The fact that compatible film is not easily available cements it’s place as a Camera of the Dead.

My Conclusions

In the second edition of the Cameras of the Dead series, I spoke about the death of film and photography in general. At that time, my fellow collectors were still reeling from Fujifilm’s announcement that they were discontinuing peel-apart FP-100C instant film and how sales of digital SLR and mirrorless cameras were on the decline from just a few years prior.

Since then, a few things have changed. In January, Kodak Alaris (the modern day version of Kodak) announced that they would be bringing back 35mm and Super 8 Ektachrome slide film, making the first appearance of a Kodak slide film since 2012. As of this writing, the film has yet to see the light of day, but a recent post on Kodak’s Facebook page suggests limited availability by the end of 2017 and a wider release next year.

Shortly thereafter, an ambitious Portland, OR film enthusiast named Kelly-Shane Fuller of Piratelogy Studios conjured up a homebrew solution to developing Kodachrome film and offers his services to anyone willing to risk $25 per roll. The results aren’t pretty, but they’re a start, and Kelly-Shane has insisted that he will continue to tweak the formulas and the process in an effort to improve the results.

Then in September, a cryptic message on the Impossible Project’s website hinted at something amazing happening on September 13th which turned out to be a rebranding of Impossible to Polaroid Originals, a release of a modern version of the Polaroid OneStep 2 instant camera (with USB charging), and the availability of a new i-type Polaroid film which promises to be less expensive than previously available films.

Finally, in October, the first shipments of a new Panchromatic black and white film by Film Ferrania called P30 began to ship to early Kickstarter backers. P30 is the first truly new black and white emulsion created by anyone in decades.

Each of these announcements certainly brings hope and excitement to an industry once thought dead. It is clear that interest in film photography is still there, even if our hobby largely depends on people shooting cameras that are usually decades old (yes, I know the Nikon F6 is still technically available), or very small scale home brew solutions for film development.

Much has been debated about the merits of analog film in a largely digital world, and I have nothing new to add to the conversation other than I love both and I will continue to shoot film for as long as these mechanical wonders continue to function and as long as I can still get usable film.

So there you have it, 3 more dead cameras. I know there will be more, so stay tuned for Chapter 5 (cue spooky music here…)