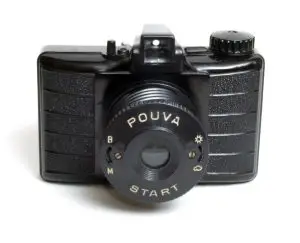

This is a Pouva Start, a simple medium format camera made almost entirely out of Bakelite. It was manufactured by Karl Pouva AG in Frietal, Germany between the years 1952 and 1971. This is the first version of the camera with a popup sports finder and was made until 1956. The Pouva Start was a simple and inexpensive camera aimed at children and beginner photographers. Despite it’s modest specs and reputation, the Pouva Start had an excellent design that was very easy to use and produced better images than it’s cheap design would suggest. Produced for nearly two decades, the Pouva Start was enormously successful, with an estimated 1.7 million made during it’s entire run.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (twelve 6cm x 6cm exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown focal length (probably ~75mm) f/8 Duplar uncoated 2-elements

Focus: Focus Free, ~8 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus Popup Sports Finder

Shutter: Spring Loaded Metal Blade

Speeds: Moment (Instant ~1/30) and Zeit (Bulb)

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Manual: http://www.camarassinfronteras.com/pouva_II/Manual_pouva_start.html

History

Karl Pouva AG was founded in 1939 by, you guessed it, Karl Pouva and it’s earliest products were rudimentary Bakelite slide projectors. Karl Pouva was born in 1903 in the Deuben district of Frietal, Germany. Frietal was a suburb of Dresden and also the home of the Welta and Beier camera companies.

Pouva’s first product was called the Pouva Magica, a simple Bakelite bodied imple projector that used a standard incandescent light bulb as it’s light source. The projector could only show one slide at a time and required the user to swap slides each time they wanted a new image. There exist early models of the Magica that are made of metal, but all consumer facing models were made of black Bakelite. The Pouva Magica was so simple, yet so successful, that it remained in almost constant production from the company’s inception to the 1980s.

In the early 1950s, using their experience with Bakelite and building simple lenses, Pouva would release it’s first camera. Made almost entirely of Bakelite, the Start had a plastic retractable lens that screwed in and out of the body. The Start went through several redesigns in the two decades it was in production. While most were black, there are black and white, and colored models as well. This site has a nice selection showing many of the different variants of Starts that were available. All Starts used 120 roll film, and produced twelve 6cm x 6cm images per roll, had a retractable lens and shutter, a single speed, and a top mounted shutter release.

The Start sold in the early 1950s for 16.5 German Marks, making it affordable for children, and those on a tight budget. Despite it’s basic design and low price, the Start was surprisingly capable, and was the launching point of the careers of many successful German photographers. The Start was so successful, that it’s design was licensed to other companies in West Germany and Poland where it was sold as the Hamaphot P56 and WZFO Druh, respectively. An estimated 1.7 million Starts were produced between 1952 and 1971 making it one of the most successful East German products of all time.

Today, the Pouva Start may or may not be a desirable camera, it depends on where you live. Here in the United States, very few people collect these as they’re uncommon here. I never found any information about whether or not these were officially exported out of Germany. Considering their cheap price in Europe, my guess is that export tariffs or taxes would have put the Start out of the affordability range for an American importer. The fact that every single fan page that I’ve found is in German, cements my theory that this camera was never sold here.

If however, you are living in one of the countries where this camera was sold, it is likely that you are very familiar with this model or possibly even had one yourself. These cameras were cleverly designed and surprisingly good for their price. The fact that they had a screw mount extendable lens, and a top shutter release that would not work unless the lens was extended made the camera “fool-proof”.

It is my hope that people outside of this camera’s home territory learn about this model as I think it’s a really neat camera, and a step up from the cheap Holga and Diana cameras favored by a new generation of film enthusiasts. Keep in mind though, that despite it’s novelty, this is a basic camera so I would advise against paying a lot for one.

My Thoughts

Any time you hear the term “children’s camera”, I instantly think of a yellow and blue Fisher Price camera made by Kodak that used 110 film, which I had as a kid in the 1980s. These were usually rubber coated plastic cameras with a single shutter speed, no focus ability, and an extremely tiny viewfinder. When I had read that the Pouva Start was a common camera given to children, I wasn’t interested. Then I saw one.

This was a handsome looking camera that was nearly symmetrical, and it had a huge flip up viewfinder. It had to be better than just some old cheap children’s camera, right?

As I researched this camera, I expected to find a bunch of Lomo-esque sample images, you know the kind, badly out of focus with extreme softness and vignetting around the edges with light leaks everywhere. Images that are counter to the perfection one might expect from a higher spec camera like a Leica or a Nikon. But a quick search for “Pouva Start” on Flickr returns some really nice looking shots. They’re not perfect of course, but an upgrade from the rudimentary images shot with other basic cameras like the Holga or Diana. It would seem that despite Karl Pouva’s best attempt at making a cheap camera, he actually made something pretty decent.

Decent is pretty much the best word I can come up with to describe the Start. You’d be foolish to expect anything even remotely characteristic of a 3, 4, or even 6 element glass lens, but when I looked at what the camera was capable of, I couldn’t help but be impressed and think, “Wow, these shots are pretty decent.”

I kept the Pouva Start on my radar, not as a “must have” but as a camera where if the price was cheap enough, I might take a shot at one. Then one day while talking to a collector from Lithuania who had a really nice looking Pentacon FM for sale, I asked if she had anything else she was selling that might help entice me to combine shipping. This Pouva Start was one she mentioned, and upon looking at it and being assured it was in proper working order, I bought it.

Upon it’s arrival, I was pleased that my Lithuanian friend wasn’t fibbing, this was a nice camera. If it was a children’s camera, it wasn’t ever used, as no kid I know, Lithuanian or American, could keep something like this so nice for so long.

The Start is made almost entirely out of Bakelite. Other than a few pieces of metal in the shutter, the frame for the viewfinder, and a few screws, everything is plastic, even the lens. The camera weighs a scant 253 grams, and when collapsed easily fits into a pocket. This has to be one of the smallest medium format cameras ever made.

The camera is simple, but almost brilliantly designed. The retractable lens and shutter screws into the body, which is quite genius as it is designed in a way to where it is impossible to press the shutter release unless the lens is fully extended. Look at the images to the left and right showing how the metal bar that fires the shutter does not come in contact with the shutter release button unless the lens is extended. This eliminates those bone headed moments like I had with a Detrola camera where I shot almost an entire roll with the lens retracted.

The lens has two settings on it’s face. On the left is a switch for the shutter speed. Your only options are “Zeit” which means Bulb, and “Moment” which is the instant speed of about 1/30th of a second. On the right is a switch to change aperture settings. The Start does not have a traditional iris, but rather a moving metal plate with two different size holes in it. The larger is labeled “Trüb” and translates to a roughly f/8 wide open setting, and the smaller, labeled “Sonne” is for bright sunlit shots where the aperture is probably somewhere around f/16.

I find this variant of the Start to be better looking than later ones. In fact, I was surprised to learn that this version with the handsome front plate predated the more mundane solid black plastic with white lettering versions that followed it. I wonder if Pouva aimed a little higher with the original model and quickly decided they needed to cut corners to keep costs down with later versions.

The viewfinder is a flip up reverse Galilean sports finder with two optical elements which show an approximation of what will be captured on film. Later versions of the Start would replace this viewfinder with a smaller fixed one. I would be willing to bet the reason for the change was that these flip up ones can easily be broken, especially when used by children. I prefer this design over the smaller fixed types because I wear prescription glasses and these are easier for me. Not to mention that when using this style of viewfinder, moving the rear element forward or backward slightly duplicates the effect of having an adjustable diopter on a more advanced camera.

Loading film into the camera is pretty straightforward, but only after opening it, which was not obvious to me when I first received the camera. Unlike other cameras from the 1950s, there is no latch or release on the side or bottom of the camera to get the film compartment open. Instead, there is a little black arm that sticks out from beneath the wind knob on top of the camera. In the previous image of the viewfinder, it is the raised black arm between the knob and the viewfinder. This arm is not labeled and isn’t even obvious that it moves at all. To open the film back, you use your left thumb and press this arm forward and it swings forward pushing the film compartment open with a “pop”.

The film door is not hinged, and comes completely off the camera, revealing a rather standard roll film compartment. Film transport is from right to left, and loads like you’d expect. The camera has absolutely no double image prevention or any type of automatic film advance, so you must be careful when advancing the film to not go past your next frame number. There also isn’t any type of cover for the red window to keep out stray light from leaking on the film. For this reason, I recommend against using super fast film like 800 speed or higher.

Feeling reasonably sure that the camera was in good working order, and with no need to replace light seals or any other type of servicing, I loaded in a roll of Kodak TMax 100 I had laying around. I thought the 100 speed film would be a good match for the Start’s single speed (roughly 1/30 second) shutter speed.

My Results

I shot the entire roll of TMax in a couple of days in late July and when the roll was finished, I put it in my “to-be-developed” pile. I have used a variety of online sources for developing my film, even relying on my friend Adam on occasion, but the two labs I use most often are Dwayne’s Photo in Parsons, KS, and Willow Photo in Willow Springs, MO. Willow has the best prices for developing of any place online, but despite their economics, I have always wanted to try developing myself.

With a peppermint schnapps sized bottle of Kodak HC-110, a bottle of fixer, a Paterson tank, and a whole lot of encouragement, I finally took the leap into developing my own film with this roll shot in the Pouva. I was apprehensive in case I messed something up, would it impact the images in a way that made me unable to give the camera a fair review? I guess there’s only one way to find out!

Without turning this into a separate discussion about developing film, I will just say that I wanted to kick myself for not developing my own film sooner! Apart from some initial struggles getting the film onto the reel, developing was super easy and the results came out great!

I was happy to see that my choice of a slightly expired 100 speed film matched the single shutter speed of the Start quite well. Above are 8 of the 12 shots from the roll and the ones I am not showing you are either second exposures of some the same shot, or just really boring compositions.

True to it’s “children’s” camera status, the Pouva Start shows heavy vignetting in all images, especially ones where the sky is visible. Softness creeps in quickly near the corners as well. It’s less obvious as I used black and white film here, but had I used color, my guess is there would be significant chromatic aberrations near the edges as well. There is also a light leak in at least 3 of these shots. After seeing these, I took a quick look at the camera to see where it could be coming from and it’s not overly obvious. The Pouva has deep door channels with no light protection of any kind. I think that a piece of thin black yarn in the door channels would suit this camera quite well and I wonder how common this problem is.

In terms of sharpness, I found that some of the images were very sharp and others not so much. It seems that the images where I used the “Sonne” setting which stops the lens down to probably f/16 were sharper. It is common with most lenses that sharpness improves stopping down the lens, but the difference is significant with this camera. Since this is a fixed focus camera, there’s no other way I could have improved the shots in the gallery above of the three houses. Each were more than 25 feet away from me and should have been well within the depth of field of the Duplar lens, yet all three have a softness to them that likely wouldn’t have improved no matter where I stood. I am still on the fence as to whether or not I think this lens is plastic or glass. On one hand, I’ve never seen a plastic lens render a shot as sharp as the first two, but then again, it did show it’s limitations wide open. If anyone reading this knows for sure, please let me know.

Looking at the others, especially the first two images, I am amazed at the sharpness of this plastic 2-element lens. I had read in other reviews of the Pouva Start that the camera is capable of misleadingly good images and if these two are typical of what this camera can do in optimal conditions, then color me impressed!

I have never had any interest in shooting a “Lomo” camera like a Holga or a Diana. I simply do not care to use a camera that is intentionally bad. While not all images need to be razor sharp, and not every light leak ruins an image, I feel as though you should always strive to achieve the best quality each camera is capable of. I am impressed at what this simple 2-element focus free camera with a single shutter speed and mostly plastic body was capable of and for that, think it’s an outstanding camera. I think the Pouva Start is handsome, it is very compact and lightweight, it was a lot of fun to shoot, and I love the images it made. Next time I take it out, I plan on seeing what it can do with color film, and if those shots are worth sharing, I’ll be sure to update this review.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Pouva Start isn’t well known in the United States, but was one of the most popular East German cameras of the 1950s and 60s. It was an inexpensive Bakelite bodied camera that was easy to use and was commonly given to children as their first camera. The design of the camera is quite clever and mostly fool proof. It’s best characteristic is that despite it’s common label of a “children’s camera”, it is capable of some really nice shots. The camera is light weight, portable, and easy to use making it a really fun camera to add to any collection. These don’t show up for sale often in my country, but am glad this one came my way and would absolutely recommend it to anyone considering giving it a shot! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 30% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 7.8 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Pouva_Start

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Pouva_Start

https://www.dresdner-kameras.de/andere_baureihen/andere_baureihen.html#Pouva

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/92304-pouva-start-another-cult-camera

http://www.analogadvocates.com/page/pouva-start

http://westfordcomp.com/classics/pouva/northcarolina/index.html

Hi Mike – I was puzzling over how to open the Pouva Start – went online – and there is your great article! My most frustrating was the Kochmann Korelle K – one of the earliest conventional shape half frame cameras (it has interchangeable lenses, too!) I had to go back to the guy I bought it from to open it!!

Hallo, toller Beitrag. Wollte nur meine Erfahrung dazu geben. Es ist so, das trotz der Auslegung der Kamera aus der Hand fotografieren zu können die Nutzung mit Stativ zu schärferen Bildern führt. Am besten mit Drahtauslöser, da der kleine Boden der Kamera nicht zu einem großen Kontakt mit dem Stativ sorgt. Aber ja, ich liebe das Teil auch und habe gerade am frühen Morgen in der Metro die Kamera wieder mit. Liebe Grüße Dimi.

Hello, great post. Just wanted to give my experience. The fact is that, despite the camera’s design, being able to take photos handheld, using it with a tripod results in sharper images. It is best to use a cable release, as the small base of the camera does not mean there is much contact with the tripod. But yes, I love the thing too and have the camera with me again on the subway early in the morning. Kind regards, Dimi.