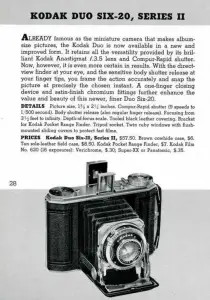

This is a Kodak Duo Six-20 Series II medium format camera which was designed by Nagel Kamera Werk for Kodak AG by August Nagel. The word “duo” was Kodak’s way of saying “half frame”, meaning the camera too 6cm x 4.5cm images instead of “full frame” 6cm x 9cm like many other folding cameras of the day. The Duo Six-20 line was made from 1933 – 1940 and was not produced after the war. The Series II in the name means it was a later variant with improved struts, viewfinder, and a chrome body. As the name suggests, the camera was designed for Kodak’s 620 format film. It was an expensive camera built to typical German standards of the day and was highly regarded both then and now.

Film Type: 620 roll film (16 exposures 6cm x 4.5cm per roll)

Lens: 7.5 cm f/3.5 Kodak-Anastigmat uncoated 3 or 4 elements

Focus: 3.5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Flip up Reverse Galilean Scale Focus Finder

Shutter: Compur-Rapid

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/kodak_pdf/kodak_duo_six-20_series_ii-02.pdf

History

The Eastman-Kodak company was originally founded by George Eastman in 1888. George Eastman was a visionary inventor and businessman who had the idea that if they could sell an inexpensive photographic film apparatus that would require customers to keep coming back to buy more film, they stood to make far more money than they would as a dedicated camera making company. Instead of getting one purchase from a customer for one or two cameras, they could have a customer for life, continually buying film.

The Eastman-Kodak company was originally founded by George Eastman in 1888. George Eastman was a visionary inventor and businessman who had the idea that if they could sell an inexpensive photographic film apparatus that would require customers to keep coming back to buy more film, they stood to make far more money than they would as a dedicated camera making company. Instead of getting one purchase from a customer for one or two cameras, they could have a customer for life, continually buying film.

Eastman’s business model was a roaring success, and it catapulted Kodak to the top of the film industry for over a century. While Kodak was always a ‘film first’ company, they didn’t ignore the camera making business either.

Kodak’s first cameras were basic box cameras with simple lenses and single speed shutters. These early box cameras were designed in a way to be cheap to manufacture, and easy to use, but just good enough that people would be satisfied with the images they made. Over the first half of the 20th century, Kodak would on occasion release mid to upper priced models to complement the basic box cameras, but they generally weren’t considered leaders in the camera making business.

By the late 1920s, if you wanted film, you might buy it from Kodak, but if you wanted a high end camera, you bought something from Germany. While Kodak had a variety of capable models at this time, they sorely lacked the precision and expertise of the German marques like Zeiss, Voigtländer, and Leitz. For this, they turned to a man named Dr. August Nagel. If George Eastman was the most important man in Kodak’s history, Nagel was second.

August Nagel was born in June 5, 1882 in Stuttgart, Germany. (There is at least one article online which suggests Nagel was born in 1867, which I do not believe to be true.) In his younger years, he worked in various small machine factories learning business and the inner workings of mechanical objects. Despite being a skilled mechanic, Nagel’s passion was photography, and he would devote his free time to the design and construction of primitive cameras.

In 1908, at the age of 26, he founded his first company with childhood friend Carl Drexel, called Drexel & Nagel of Stuttgart. Drexel & Nagel’s first camera was a very compact camera called the Contessa No.1 which made 4.5cm x 7cm images on what I can only assume was some type of early roll film. In my research for this article, I was not able to find any images or any other information about what this first Contessa would have looked like.

Drexel & Nagel saw almost immediate success, and in 1909, renamed itself to Contessa Camerawerke Stuttgart, and by 1910 had developed as many as 23 different models, many of which were exported all over the world.

By the start of World War I, Contessa Camerawerke employed over 500 people, and during the war, would switch production to making armaments for the German war effort. After the war had ended, the German economy was in disarray and many German companies were unable to stay in business. One of these companies was Nettel Camerawerk from Sontheim am Neckar, Germany. Nettel had been in business since the early 1900s as a maker of folding medium and large format cameras.

In 1919, Contessa Camerawerke would take over the floundering Nettel Camerawerk and become Contessa-Nettel AG. An early Contessa-Nettel model was called the Cocarette which was a folding bed roll film camera that had a unique film loading design in which the film compartment would slide out of the bottom of the camera as it’s own separate piece. A new roll of film would be installed onto the spools and the entire film compartment would be slid back into the body of the camera. This guaranteed a near light proof film compartment and also had the advantage of a perfectly flat film plane, guaranteeing consistently focused images.

Although Contessa-Nettel had success in the 1920s, the entire German economy continued to suffer after World War I, causing a lot of instability in German industry. While the largest German companies were able to continue operations on their own, there was a growing number of smaller German companies that were struggling to stay in business. Contessa-Nettel AG was not immune to the struggles of the economy, and as a result in 1926 would partner with several other German camera makers like Erneman, Goerz, ICA, and Zeiss to form Zeiss Ikon AG.

While the idea of combining forces of several smaller companies into one larger company was probably a good way to stay in business, August Nagel found himself for the first time in his career to not be in charge of his own company. Prior to his partnership with Zeiss, he had free reign to design and release new models to his heart’s content, but now, he had to answer to a board of directors, all made up of executives from these other companies who didn’t always see eye to eye with Nagel’s vision.

In addition to his creative differences with the board, the other board members all had higher education backgrounds which Nagel lacked and he was often put down and ignored by his more educated peers. As a result, only 2 years after merging with Zeiss-Ikon, August Nagel would leave the company to form his own company, “Dr. August-Nagel-Fabrik für Feinmechanik”, or simply Nagel Werke.

Regarding his time working for Zeiss, it is said that Nagel kept a pretty big chip on his shoulder regarding his poor treatment while working for Zeiss. It’s this chip that is likely why he insisted on referring to himself as “Dr.” August Nagel, even though his doctorate was an honorary one bestowed upon him in 1918 by Freiburg University in recognition of his contributions to the German camera industry. It was common during interviews and speeches that Nagel would be brutally honest regarding his opinions of the board.

The rejuvenated Nagel was once again free to design his own models that were built to a very high standard and quickly earned him praise. Some of Nagel’s designs during this period were the Vollenda, Pupille, Librette, and Recomar. In the early 1930s, the German press reported on Nagel’s success saying “In spite of the economic misery of this period, Dr. August Nagel succeeded in bringing his new company to a high profile in a short time and to give world-class quality (sic) to his products. “

By the early 1930s, Nagel Werke had restored August Nagel’s reputation as a world class camera maker. With over 2 decades of experience making high quality and well performing models, he was highly respected all over the world. Despite his accolades and success at making quality cameras, the German economy was still poor and political changes were on the rise, both of which held back Nagel’s ability to continue to innovate.

Conveniently, around this time Kodak was looking to improve their reputation in the camera industry by offering a lineup of German designed cameras bearing the Kodak name. In 1931, representatives from Kodak offered to merge with Nagel Werke giving them the capital and support of one of the largest photographic companies in the world, with the understanding that August Nagel would remain as Managing Director and Chief Designer of the new Kodak / Nagel AG. Nagel would retain his title and stature from his own company while having the creative freedom to continue to develop and release his own models, while working for Kodak. It was a win win for both Kodak and Nagel. In December 1931, the merger was completed for an undisclosed amount of money, and with Nagel Werke’s merger into Kodak, came most of Nagel’s earlier models like the Pupille, Vollenda, and Recomar. Most of these models would be sold under the Kodak name, but would otherwise be unchanged.

Almost immediately after joining Kodak, Nagel would begin working on new models. Although many people know Nagel as the father of the Retina (which itself borrowed design elements from the 127 film format Nagel Vollenda), and 135 format 35mm film, he also helped Kodak design new cameras for their new 620 film format. 620 film used the same film stock as 120 film, but came on narrower spools that had a smaller core, allowing the film to be installed into more compact cameras. Since Nagel already had a great deal of experience working on compact cameras, it was a perfect challenge to design a new camera using Kodak’s compact 620 film format, but would be built to high specifications and have the exemplary build quality that Nagel was known for.

Released in early 1933, a full year before the Retina would debut, Nagel’s new camera would be called the Kodak Duo Six-20 and it was his first all new design working for Kodak. Available with either a Kodak Anastigmat, Schneider Xenar, or Zeiss Tessar lens with either a maximum aperture of either f/3.5 or f/4.5, most had Compur or Compur-Rapid shutters, although a few are known to exist with Prontor or Kodak shutters. Which combination of lenses and shutters you could get depended on where in the world the camera was purchased. For example, the Zeiss lens models were only sold in Germany, whereas most models sold in the US had the Kodak Anastigmat lens. The early Duo Six-20s have an ‘art-deco’ styling that was popular at the time and had black painted bodies. In 1935, the Duo Six-20 sold in the United States for $52.50 with Kodak Anastigmat f/3.5 lens and Compur shutter. This is comparable to about $937 today.

In 1937, the Series II model would be released with a satin chrome plated body, a better viewfinder, an improved door release system, and improved folding struts. The Series II cameras came with nearly the same combinations of lenses and shutters as the earlier models and in 1938, had a list price of $57.50 with Kodak Anastigmat f/3.5 lens and Compur-Rapid shutter. This is comparable to $983 today.

Finally in 1939, came the third Duo Six-20 model, this time with a coupled rangefinder. In order to accommodate the design of the rangefinder, several significant changes needed to be made to the camera. For one, film travel was reversed, now traveling from left to right instead of right to left as in the earlier models. This necessitated moving the wind knob to the other side. Other changes were the inclusion of an automatic exposure counter so that the photographer did not need to rely on the red window on the back of the camera, and revisions to the focusing system to accommodate the coupled rangefinder.

Although the RF version of the Duo Six-20 was undoubtedly the most advanced of any Duo models, it’s debut in September 1939 coincided with the break out of war in Europe. Production only lasted for a couple of months and it is estimated that only 2000 were ever made before production was halted in early 1940. Even though Kodak AG was owned by an American company, it’s location in Germany meant that it fell under the jurisdiction of the German government and as a result, was ordered to stop camera production and work for the benefit of the German war effort.

August Nagel would die on October 30, 1943. It is unclear if this had anything to do with the war itself, or if he passed away due to natural causes. In my research for this article, I found absolutely no evidence that Nagel was ill, or had any kind of declining health, so I have to imagine that whatever caused his death, was sudden.

Upon his death, control of Kodak AG would pass onto his son, Helmut Nagel, and it was perhaps the absence of the elder Nagel that when the Kodak AG factory would re-open in 1945, the decision was made to focus solely on 35mm cameras like the Retina. As a result, all roll film Nagel models from before the war would be discontinued, never to be made again.

According to “Kodak Cameras: The First 100 Years” by Brian Coe, an estimated 81,000 Duo Six-20s were made between 1933-1940. If there were around 2000 of the coupled rangefinder models, then there were around 79,000 of the ‘Art Deco’ and Series II models, but there isn’t any more information about what the split was. I will guess that the Series II was the more popular model, but that’s only speculation on my part.

Today, the Kodak Duo Six-20 isn’t anywhere near as well known as the Retina, but being a Nagel model, they are highly collectible by people who have an interest in Kodak, Nagel, German cameras, or just any kind of cool camera. Despite their low production numbers, something that perhaps helps their availability was that they were extremely well made, and as a result, many still survive to this day. As I write this article, a quick search of eBay returned 13 Kodak Duo Six-20 cameras for sale. Sold prices for the non rangefinder models are in the $20 – $60 range, but the rangefinder models (which are far more rare) well exceed $100.

Regardless of which variant of the Duo Six-20 you might find, it is an extremely attractive and capable camera that looks just as good sitting on a shelf as it does making photos. Unlike non-German made Kodaks, the bellows on all Duo Six-20s are made of leather and as a result generally are in good condition today. If you have the opportunity to pick one up, I absolutely recommend it, as it’s a wonderful piece of history and a very capable camera.

My Thoughts

I love German cameras, I love cameras from the 1930s, and I love 6×4.5 folding cameras, so to have a German camera from the 1930s that shoots 6×4.5 images, I figured the Kodak Duo Six-20 should be a winner. I am happy to say that for the most part, it is. I don’t think August Nagel ever made a bad camera. They’re all built with the highest level of German precision, using optically excellent lenses, great shutters, and leather bellows that almost always are in good shape today.

The Duo Six-20 was the first camera designed by Nagel once he started working for Kodak, and was the predecessor to the Retina. It is likely that development of both cameras happened at the same time, and although the two cameras use completely different formats of film, they have a lot of the same great attributes, including one not so good one. Both the Retina and Duo Six-20 use a helical focus mount which pushes and pulls the lens standard forward and backward when the camera is opened. Like the Retina, the Duo Six-20 must be set to infinity focus before closing the camera. Attempting to close the camera with the lens at any position other than infinity will cause it to bind and hit the door. If done gently, it’s not a big deal, but when forced, will cause damage to the camera. Over the course of the 80+ years since these cameras were made, the chances are quite high that at least one person, one time, forced the camera shut causing permanent damage. As a result, it can be difficult to find one in perfect working order.

Sadly, this is what happened to the Duo Six-20 being reviewed here. When I received it, I had noticed that the Compur shutter was sluggish and needed some cleaning. That wasn’t a big deal as I’ve taken apart and cleaned a number of Compur shutters and the process is mostly the same regardless of camera. I explain my process for cleaning leaf shutters in my ‘Breathing New Life into Old Cameras’ article if you’d like to try it yourself.

As I dove into the Compur shutter, I noticed that the shutter release arm was bent, likely due to it being out of position when the camera was folded shut. I thought that simply straightening it back out was all it needed, but there were more problems inside the shutter. At some point in this camera’s past, the camera was closed incorrectly, bending not only the shutter release arm, but also other parts inside of the shutter that connect to this arm. In the image to the right, a yellow arrow points to the shutter release arm, and three red arrows point to dependent parts that were also either bent or misaligned. In addition to the bent parts, the pivot points where these pieces move around seemed to have been damaged in someway, causing them to have much more play than they should. This had the side effect of not allowing the shutter to consistently cock and stay cocked, and it also made releasing the shutter very difficult.

I did my best to bend things as close as possible back to their correct shapes, but after putting the camera together, I noticed that the shutter would often cock and then immediately release itself without staying cocked, and in the cases where the shutter did stay cocked, I was unable to release it using the top shutter release. I had to use my finger and directly push the shutter release on the shutter itself.

With the camera back together, I was a bit dismayed at my inability to get it into proper working order. I had a brief thought that I would include this in a future “Cameras of the Dead” article, but this camera was too good for that. I was able to get the shutter to fire at all speeds, the glass elements were very clean, the bellows still appeared to be light tight, and the body was in nice shape. This camera had to be used, despite the condition of the shutter.

I loaded in a roll of Kodachrome II 620 film that had expired in 1991. I have had good luck with expired Kodachrome II from the 80s, so I thought this roll from 1991 should be in pretty good shape. I used Sunny 16 with 2 stops overexposure for all of the shots. I tried to shoot exclusively in bright sunlight to maximize contrast and color accuracy. Depending on the results I get from this first roll, I may shoot this camera again with a roll of fresh 120 rolled onto a 620 spool.

In use, the Duo Six-20 is very much like a “medium format Retina”. Although larger than a Retina, it is compact compared to other medium format folding cameras. The build quality is superb and on par with any other Nagel designed camera from the 1930s.

The viewfinder is of the reverse Galilean type with two separate pieces of glass mounted in a folding optical frame. I personally find these type of viewfinders to be extremely easy to use because they’re large and bright, very easy to clean, and allow for subtle adjustments to the rear frame as a sort of early adjustable diopter. As a person who wears prescription glasses 100% of the time, folding optical viewfinders are far easier than the tiny integrated finders found on other cameras of the 1930s-1950s.

The controls of the focus, shutter speed, and aperture are all standard fare for a camera of this type. Everything is located around the perimeter of the shutter itself and can be a bit difficult to change with the camera up to your eye, so you’ll want to get your settings correct before composing your image. Most Compur shutters from the 30s and on were of the rim-set design where the shutter speed is changed via a large chrome ring around the circumference of the shutter. Normally, this ring should be easy to move, but if your shutter hasn’t been cleaned, this ring can be difficult to move. Dirty Compur shutters often have issues with the shutter speeds themselves, especially at the fastest speed and speeds 1/25 and below. If you are shooting with any camera with a Compur shutter that has not been cleaned, I recommend sticking only to 1/25, 1/50, or 1/100 shutter speeds.

Although I was unable to use it on mine, the Duo Six-20 has a top shutter release which activates the shutter release arm through a complicated series of linkages inside of the door. Is it this folding design that causes trouble when trying to force the camera shut. Not only must you make sure the camera is set to infinity focus before closing it, but you also have to press and hold a release bar at the front lip of the door to close the camera. Doing so unlocks a latch in the hinge and also assures the shutter release arm will be able to properly fold. If you are lucky enough to have a Duo Six-20 with a good linkage, please take care of it, because once it is bent, it is very hard to correct.

The back of the camera has two windows that are both needed for proper advancement of the film. 620 film uses the same exposure numbers as 120 film, and neither have dedicated numbers for “half frame” 6cm x 4.5cm images. You have to use the numbers 1-8 for 6cm x 9cm images and double them up. Since the film rolls from right to left, when starting a new roll of film, you must line up the number 1 in the right frame and make your exposure. Then for the second exposure, advance the film until the number 1 is in the left window and make your second exposure. For the third frame, you want number 2 in the right window and then move the number 2 to the left frame for the fourth exposure. Keep doing this, being sure not to roll a number past the second window, or else you’ll waste an exposure. The 16th exposure on the roll will be done with the number 8 in the left window, and after that, your roll is finished.

Like most Kodak cameras of the era, there is an uncoupled depth of field calculator on the right side of the top plate. This can be useful as a reminder when using this as a zone focus camera. Looking at the image to the left, you can see that with the camera focused to 12 feet and the aperture set to f/11, everything from around 8.5 feet to about 25 feet will be in focus.

Overall, the Kodak Duo Six-20 was a great camera. I am saddened that mine was crippled in the way it was, but I cannot criticize the camera for it’s shortcomings. The thing is 80 years old and the only reason it is in the state it is in, is because of misuse by someone else. This type of problem won’t happen with proper usage. Had mine been in better shape, there’s no reason this camera couldn’t still be used as an every day camera.

My Results

Of all the opportunties I could have taken to shoot the Duo, I chose an Easter egg hunt in early April. It was a particularly bright and warm day, so I figured it would be a great chance to show off what that Kodak Anastigmat lens could do.

When shooting a 620 film camera, you have two choices, respool 120 onto 620 spools, or just use an expired roll of 620 that you have laying around. Since I still have quite a supply of old Kodacolor II 620, I chose the latter. I have had really great luck with old Kodacolor II and know that a +2 over exposure usually gets usable images.

Normally I try to play it safe when shooting a camera for the first time, but I really stacked the odds against myself this time shooting a camera with a malfunctioning shutter, using 30+ year old expired film, at an event with fast moving children. Would I regret my decision?

Looking at these images, I can state that from a composition standpoint, they’re not exactly my best work, but from a technical standpoint, they confirm a thought I’ve had in my head ever since the day I acquired this Kodak Duo Six-20.

Medium. Format. Retina.

This camera might not have an official Retina name, and may have never been marketed as such, but it is clear that everything that makes the Retina series so popular, is here, just with a larger film format. Like any camera made by Nagel, the Duo is built to incredibly high standards. The lens may not have the words “Zeiss”, “Leitz”, or any other number of German names, but make no mistake, the Kodak Anastigmat f/3.5 lens is extremely capable. I could never find any conclusive evidence as to whether this is a 3 or 4 element lens, but my gut tells me this has to be a 4-element, possibly even a Tessar design.

I was extremely pleased with the sharpness and quality of the images. The expired Kodacolor II film made outstanding images with excellent color and contrast. Other than one image with a light leak on it, I detected no fogging or imperfections of any kind in any of the images. There was a subtle blue color shift in all of the images, which was easily correctable in Photoshop. For comparison sake, the image to the right is the original, unedited version of the 5th image above, straight out of the scanner. As you can see, a subtle warming adjustment was able to balance out the blue shift, and an ever so slight touch to the contrast slider is all that was needed to get lifelike colors from the expired film.

I was extremely pleased with the sharpness and quality of the images. The expired Kodacolor II film made outstanding images with excellent color and contrast. Other than one image with a light leak on it, I detected no fogging or imperfections of any kind in any of the images. There was a subtle blue color shift in all of the images, which was easily correctable in Photoshop. For comparison sake, the image to the right is the original, unedited version of the 5th image above, straight out of the scanner. As you can see, a subtle warming adjustment was able to balance out the blue shift, and an ever so slight touch to the contrast slider is all that was needed to get lifelike colors from the expired film.

I am pleased to see that despite it’s mechanical maladies, the Kodak Duo Six-20 delivered on the promise of quality images like I had hoped. I have always been a fan of the 6×4.5 format, and combined with the excellent lens, and gorgeous nickel and leather pre-war styling, the Duo Six-20 is a winner. I do not know that there is any hope that this camera could ever be fully restored without a full shutter swap, so it might end up being a display piece as I wait for another to cross my path. I don’t normally buy duplicates of cameras once I own them, but this might be that rare exception. If that day ever comes, I’ll be sure to update this review with more results from a more capable camera.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Kodak Duo Six-20 is yet another example of a quality pre-war camera developed by August Nagel while employed by Kodak. Every part of the camera from the satin chromed metal to the elegant hinges to the leather bellows to the excellent Kodak Anastigmat lens to the Compur shutter is built with high German precision. Although my camera had some faults, I was still able to get some spectacular results from it. Had mine been in perfect working order, it’s a camera I could see myself coming back to time and time again. This is an excellent camera that is fun to use, makes amazing photographs, and looks very nice sitting on a shelf. I highly recommend this camera. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | none | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.6 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Duo_Six-20

http://kodak.3106.net/index.php?p=302&cam=914

http://elekm.net/photos/duo-six-20/

Another really interesting review. I used 620 many times in my younger days. I well remember aligning the shot number in the red window of my old Kodak. Keep the reviews coming. Thanks, Jeff Oliveira in CA.

It was usual in the era for Kodak to relabel Schnieder Krueznach lenses for the US market. For instance, the Anastigmat lens on the Kodak Regent is actually an SK Xenon, the same lens evolved into the Anastigmat Special, and later the original Ektar. The lens on the Duo 620 is likely a Xenar or Xenon rebadged as a Kodak Anastigmat.

Oh, and “Anastigmat” will not refer to a triplet lens, it refers to a double-gauss or Tessar-type lens.