This is a Vivitar 35ES 35mm rangefinder camera made by Cosina of Japan around 1978. The Vivitar 35ES was one of many variants of this model all made by Cosina. There were versions sold by Minolta, Revue, Prinz, and possibly others, all made by Cosina. Unlike most rebadges, there were subtle variations between all of the different variants, some with or without external flash ports or slightly redesigned top plates. One thing that remained constant between all models is the excellent 6-element 40mm f/1.7 lens which was very highly regarded and capable of excellent photographs. The Vivitar 35ES and its cousins represented the last generation of compact rangefinders with fast f/1.7 lenses, manual focus, and auto exposure control. The industry largely moved away from this style of camera in the years that followed, favoring fully automatic point and shoot cameras with less spectacular lenses.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 40mm f/1.7 Cosina coated 6 elements

Focus: 3′ to Infinity

Type: Coupled Rangefinder

Shutter: Metal Leaf

Speeds: B, 1/8 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: CdS located within filter ring

Battery: PX675 1.35v Mercury

Flash Mount: Hotshoe

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/vivitar_35es.pdf

History

Vivitar was a common name in the photography industry in the 1970s and 80s as a brand of inexpensive point and shoot cameras, and some pretty decent SLR cameras and lenses. The company’s highlight line were the Vivitar Series 1 lenses which came in pretty much every mount imaginable.

Although their product lineup consisted of a huge variety of other photographic products, they weren’t exactly known for their cameras.

Originally founded in Santa Monica, CA as Ponder & Best in 1938 by Max Ponder and John C. Best, the company was a distributor of photographic products made by a variety of German and Japanese companies. At their peak popularity in the 1940s and 50s, Ponder & Best had American distribution agreements with Voigtlander, Franke & Heidecke, Olympus, Mamiya, Petri, and several others.

In 1964, Ponder & Best would lose two of it’s most lucrative distribution agreements with Franke & Heidecke and Olympus which caused the company’s focus to change to rebranding the products they sold in an attempt to build their own brand identity.

The product name chosen as their new “brand” was Vivitar. Early Ponder & Best lenses were labeled P&B Vivitar, but later, all products solely carried the Vivitar badge.

While Vivitar rebranded more than just lenses, it was their SLR lenses that brought the company the most success. Their business model was to sell quality lenses for prices cheaper than the OEM names in an effort to piggy back on the success of top tier companies like Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, and Minolta.

In 1975, Vivitar would begin a relationship with the Japanese company Cosina, and release a wide number of Cosina made cameras for sale in the United States under the Vivitar name. The earliest models were SLR cameras using the M42 screw mount. These early M42 SLRs were basic models meant to be sold at discount prices for entry level photographers who might be interested in Vivitar branded lenses.

Starting in the late 70s and lasting into the early 90s, Vivitar would sell Cosina made SLRs using the Pentax K-mount. As with their M42 offerings, these were all entry level cameras aimed at the bargain end of the market.

While SLR models dominated the Vivitar camera portfolio, the company did release other types of cameras as well, including a few 35mm rangefinders. Although most of these Cosina made rangefinders were of the mid to low end variety, there was one notable exception, the Vivitar 35ES from 1978. The 35ES was built alongside several other capable cameras like the Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII and Revue 400SE. Sharing the same lens, body, and internal electronics, all of these cameras were examples of a common practice called brand engineering.

Edit 4/17/18: In an earlier version of this article, I included the Konica Auto S3 as another Cosina made sibling to the Vivitar 35ES. I have found numerous posts online suggesting that the Konica Auto S3 was made by Cosina for Konica and then later released by Minolta, Vivitar, and other companies. Looking at the two side by side, it is very easy to see why they might be the same camera.

Since this review was posted in December 2016, I received responses both from Fred Baker and Kevin Rosinbum who disagreed with this assessment saying that the Konica Auto S3 was in fact made by Konica and not Cosina. After lengthy emails back and forth (which I kept out of the comments section), we came to the conclusion that the two cameras share many similarities, including some internal ones like the metering system, trap needle, exposure counter, and some others.

Despite these similarities, there is simply no evidence to support that Cosina made the Konica Auto S3 a full 5 years before these other cameras were made. I still believe that there’s more to this story, but unless someone with first hand knowledge from back then comes along to clarify what really happened, I decided to remove most references to the Konica Auto S3 from this article, in the interest of not spreading incorrect rumors.

The Vivitar 35ES was a handsome and compact rangefinder that was only available in black. It came with an excellent 40mm f/1.7 lens with 6-elements in 4 groups that had a reputation of delivering exceptionally sharp images. In fact, the Vivitar’s more well known Minolta sibling have become two of the most desirable compact 35mm rangefinders, with working examples fetching prices over $100 today.

I can’t honestly say whether or not the 35ES was a success or not. My guess is it sold in modest numbers but likely was never a top seller. For one, they don’t come up for sale as often as the other variants, and two, Vivitar didn’t continue releasing quality rangefinders after this model, so it’s likely there wasn’t enough of a demand for them to be compelled to continue the line.

Still, for those lucky enough to have shot with one, they are extremely capable cameras. Their good looks, compact size, and excellent 6-element lens make for a very capable shooter.

Today, these cameras can have some value for those who know what they are. One thing working in favor for a bargain hunter like myself is that many people dismiss this camera as just another cheap Vivitar. Helping that misconception is that Vivitar made several other low spec cameras like the 35EE, and 35EF that look very similar to the 35ES. At a quick glance, you might not even notice the large f/1.7 lens. Still, its a worthy camera to add to any collection.

Repairs

Ever since I picked up a Minolta Hi-Matic 7s, I had been curious to try out the 7sII due to it’s more compact size, equally impressive lens, and automatic exposure. To date, I still have yet to try one as they rarely go for sale for anywhere near a price range that I am comfortable spending. After learning more about the variants of the Minolta, I widened my search to the other variants. This 35SE was the first to cross my path in my price range and thinking I had a nice example, I bought it.

Upon receiving it however, I was saddened to discover what I would later learn is a very common problem on all of these Cosina variants which was that no matter how much light was detected, the aperture would always stop down all the way to the smallest setting of f/16 any time you pressed the shutter release. I confirmed the meter was working correctly with a fresh battery and that I wasn’t just missing some setting on the camera that needed to be turned on or off to make it work correctly. There was definitely a defect in the camera that needed to be repaired. Making matters worse, the Vivitar 35ES does not offer any direct control over the aperture. The only manual settings were shutter speed and a limited flash guide setting.

I scoured the internet trying to find some information about what could be causing my problem, but since the Vivitar 35ES isn’t exactly a common model, I struggled to find any useful information until I expanded my search to it’s variants. It was then when I found this Flickr page by Brian Legge which details a repair on the Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII in which a pin has broken off inside of the camera, causing the aperture to always stop down to f/16.

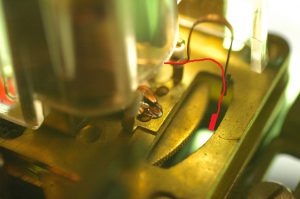

If you read the descriptions of the images from Brian Legge’s page, he explains that the camera is designed to always close the iris all the way every time the shutter release is pressed. Whenever an aperture setting wider than f/16 is needed, there is a curved metal pin that is supposed to protrude down into an area of the camera which “traps” a gear which is directly linked to the aperture iris preventing it from going all the way down to f/16. So, for example, if the camera detects that f/8 is needed instead of f/16, this pin moves into a spot where when the aperture begins to close, it gets trapped by this pin at the exact point where the aperture is at f/8.

The problem is that a piece of this pin can break off causing it to not be long enough to trap the gear. Since the pin isn’t trapping the gear, the iris always closes down to f/16 no matter what is needed. The only way to repair this, is to find a way to solder some kind of extension onto the end of this pin so that it’s long enough to reach into the part of the camera where it can trap this gear.

If this all sounds confusing, just look at the image to the right. This image is from Brian’s Flickr page and was not taken by me. That curved piece of metal is the pin that is supposed to be protruding down into that curved hole. The curved piece of metal with the small teeth around it’s perimeter is the gear that is supposed to become trapped. In the image to the right, this shows the camera in it’s not working state. This is exactly how my 35ES looked when I took it apart.

Removing the top plate of the Vivitar 35ES is quite easy. All you need is a lens spanner and a set of precision screwdrivers. Remove everything in the order of the numbers in the image to the left. There are 2 screws under the rewind crank and a third screw on the side of the top plate, above the door hinge. If you’ve ever removed a top plate from a rangefinder camera before, you’ll find that the process is very simple.

Once you are able to pull the top plate off, there will be a flash sync wire that you can either de-solder, or if you’re careful enough, you can leave it connected to the top plate and just set it aside.

It is very difficult to explain in words where the image above of the curved pin actually is in the camera, but the “bottom” of the pin in the image is actually facing toward the front of the camera. This pin is located in the proximity of the shutter release button. In the image to the left, the pin is inside of that curved hole, right above the 35ES logo.

The area in which this pin is located is very small, and there is not very good access to it. It would be impossible to solder any type of extension to the pin without fully disassembling the camera, which was something I didn’t want to attempt.

Knowing that all I needed to do was “extend” the pin so that it reached farther down into that curved hole, I made the executive decision to attempt to bend it in manner which would pull it farther into that hole. Using a pair of needle nose pliers, I was able to just grab hold of the tip of that pin and bend it in a way to where it looks like my excellent drawing to the left. You want to get the tip of that pin to just barely line up with that curved gear. Once it is in position, you can test fire the shutter to see if it successfully traps the gear. It is a lot more obvious to see it in person.

It took me a bit of trial and error to get it right, but after I got it, that curved pin will never look like it originally did, but it worked. I could see that when I would fire the shutter, the aperture would only stop down to an appropriate setting for what the meter would allow for.

Thankfully, the 35ES required no other repairs, so I put everything back together, loaded in some film and went shooting.

My Thoughts

I already covered how the Vivitar 35ES is heavily based off other Cosina made rangefinders released under a variety of names, and while there are slight cosmetic, and in some cases physical differences (the Vivitar lacks a PC flash port that is available on other models), all of these cameras are basically the same and have the same pros and cons so I can safely say that my thoughts should reasonably translate to any of the other models. I likely won’t ever pay the asking prices for the other models, so this is probably the closest to a review of those models I’ll ever give.

With that in mind, I’ll start with the 35ES’s signature feature, which is it’s size. While the rangefinder camera had been steadily falling out of favor all throughout the 1960s, there was still a limited appeal in the 70s for compact rangefinders with fixed and fast (sub f/2) lenses. Cameraquest has a great article summarizing all of the different compact 35mm rangefinders of the 70s, so I won’t repeat them here, but in a nutshell, here was the competition in this market (excluding the three variants of the 35ES).

- Olympus RD

- Canonet G-III QL17

- Yashica Electro 35 CC and GX

I have no evidence of this, but based on the sheer availability of them on eBay, I’d predict that the Canonet was the most popular. I previously reviewed the Canonet G-III QL17 here so a lot of what I say will be in comparison to that camera.

Moving past the size, the second most widely talked about advantage of this camera is the 6-element lens. I am pretty sure that the lens is identical in all variants of this camera as I doubt Cosina changed the optical formula for each respective model. This is a good thing though because the lens on the 35ES is spectacular. Vivitar was never known as a brand with high spec cameras, so I’ll declare that the 35ES represents a rare high point for a Vivitar branded model. It is unlikely you’d ever see a difference in image quality, sharpness, or rendering between the 35ES and any of it’s variants.

Neither a pro or a con is the shutter. With a top speed of 1/500, the Vivitar 35ES is comparable to pretty much every other model in this series. Furthermore, all models in this class are flash synced at all speeds, which is something unique to leaf shutter cameras. Try doing that on your focal plane shutter SLR! The Canonet has a slowest speed of 1/4 second, compared to 1/8 in the Vivitar, but that is not meaningful enough to list it as a con.

All cameras in this class have shutter priority auto exposure which is more than useful for the target market these cameras were aimed at. I generally prefer aperture priority auto exposure, but shutter priority probably made more sense from a marketing standpoint as it is easier to explain to a novice how shutter speeds work, compared to aperture sizes and f-stops. The Canonet, Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII and Konica Auto S3 however, allowed for full manual override if so desired. This feature alone seems to be the sticking point for most people who make a “Best Compact 70s 35mm Rangefinder” article and whether or not it’s something you would use any of these cameras for, it’s definitely worth mentioning.

From a feature standpoint, the Vivitar has only minor nitpicks. It’s lack of a PC sync port probably wasn’t a big deal breaker for someone in the 70s looking for an inexpensive rangefinder with a good lens. It has a hot shoe and is flash synced at all speeds which was already the standard by 1978 when this camera debuted. I doubt many PC ports on other cameras of the era were ever used. All of these cameras still used mercury batteries, but at least the 35ES uses the PX675 which is easy to substitute today. I do not know if the camera has a voltage stepping circuit inside, or if it’s just really flexible with voltage, but using a 1.5v silver oxide battery in mine didn’t seem to produce any ill side effects.

Other features are a flash guide system which I don’t even fully understand myself, so I wont comment any further on it, a viewfinder with a visible aperture scale, and parallax correction marks. The Canonet gets an extra point for having active parallax correction, but the Vivitar gets by with some notches in the brightlines.

My one true complaint about the Vivitar 35ES which is sadly common on many rangefinders from the 1960s and 70s is an incredibly short focus throw. This was likely necessary to maintain the compact size of the body, but the difference between focusing at 3 feet compared to infinity is roughly 1/10th of the entire circumference of the lens. Look at the image to the left. The red mark is at 3 feet. The infinity symbol is less than an inch away to the right. A twist of less than 36 degrees gets you to infinity. This can make precise focus adjustments in the viewfinder difficult. I guess it’s nice that the scale shows both feet and meters though.

The Vivitar 35ES often flies under the radar in discussions of “best compact rangefinder” but it’s definitely not any less deserving of high praise models like the Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII. In a head to head comparison, I think the Canonet G-III QL17 tops them all. If you are someone who is eager to shoot with a camera like this, they’re all great choices, so my best recommendation would be pick which ever model you can find the easiest and for the least cost. If however, things like full manual control, a 1/4th second shutter speed, or parallax correction are important to you, then the Canonet is your best choice. If you are specifically looking for an alternative to the Canonet, its worth checking eBay for this model as not as many people are aware of how good it is.

As with every camera I review, we can talk about their pros and cons til we’re blue in the faces, but how about those results?! I loaded up a roll of trust Fuji 200 and went shooting

My Results

Whenever I test out a new camera, I always try to use it in optimal lighting conditions. Bright spring and summer days are ideal as I have a lot of places I can take a camera to in an effort to use it to it’s strengths. By the time I had a chance to shoot with the 35ES, autumn was in full swing, so I took it with me on a family trip to Dollinger Farms, near Joliet, IL right before Halloween. The weather was heavily cloudy and on the verge of raining the entire time, so my lighting choices were not optimal. Below represent some of the highlights of that first roll.

As advertised, the images are incredibly sharp and show no signs of vignetting, chromatic aberrations or any other sort of defect characteristic of a low spec lens. Simply, the 6-element Cosina lens is as good as any of the era, and a higher spec camera would not offer anything in the way of a “better image”. Any imperfections in the images above are entirely the fault of the person behind the lens and mother nature herself.

The last three images in the gallery above were shot in very low light with the lens wide open. The two of the boy playing in corn was inside of a corn silo with the only light being an open window 20+ feet in the air. Not only was the camera at f/1.7, but I was shooting at something like a 1/10 second shutter speed so motion blur is definitely visible, yet I think the images came out great. I doubt any modern smartphone or compact point and shoot digital camera would have done as good of a job with these same shots.

While shooting with the camera, I generally liked the experience. Sure, the focus throw was very small, but that’s something I had expected due to how common this was on other cameras of the era. I had no complaints with the viewfinder. It’s bright and large enough to use with prescription classes, and while the aperture scale is a nice feature, its not something I paid much attention to. I often wonder what novices thought of these numbers when they used these cameras back then. “Those must be photography numbers!”

If you’re expecting me to lead up to some big reveal about a super awesome or horribly negative declaration I can make about this camera, I hate to disappoint you as that’s really all I can say about the Vivitar 35ES. I can’t help but have a feeling of “ho-hum” about it. It’s certainly not a cheap camera by any means, but it lacks the weight and perceived toughness of the all metal rangefinders that preceded it. Sure, its small, and that does count for something, but unless I’m going to slip it into a front jean pocket, I don’t mind using slightly larger or heavier cameras. In fact, I enjoy it. There’s something about the tactile feel of cold metal in your hands. A camera with thick ridged focus rings, a stout frame advance, and the knowledge that if you were to drop it, the camera likely would continue to forge ahead, unphased by it’s gravitational misfortune.

Simply, the Vivitar 35ES is a satisfactory camera with a great lens, easy to use controls, and a compact size that doesn’t get in the way of anything. Yet, in it’s efforts to not draw attention to itself, you end up with a mostly forgettable experience. In 1978, an “unforgettable” camera was probably a good thing as this likely would have been the only camera owned by a family whose sole purpose was to capture precious moments, but as a collector and enthusiast of old film cameras, this thing is “too” forgettable. I have so many other models to choose from when I want a 35mm rangefinder, that I doubt this one will come to the top of the queue often, if ever.

So, while it probably seems like I am left with a sour taste in my mouth, I’m not. The Vivitar is a good camera that makes great images and is easy to use. If that’s all you’re looking for, then by all means, add one to your collection, but I would challenge anyone to come up with a passionate defense of why you think this camera is anything better than “forgettable”.

My Final WordHow these ratings work |

The Vivitar 35ES is the little known cousin to the much more popular Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII. It was an example of late 70s brand engineering and has all of the great attributes of those other cameras, but without the notoriety. It’s 6-element lens is as good as they come and the camera does nothing to impede your ability to get great shots. While this praise is often reserved for the best cameras, the Vivitar 35ES has a ho-hum design, and offers an underwhelming user experience. I have nothing bad to say about it, but there’s also little to differentiate it between it and many other equally capable cameras in my collection. If all you need is an easy to use and compact 35mm rangefinder with an excellent lens, this is your camera, just don’t expect to be excited while using it. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 because this camera deserves better than a 5.0 rating, so I’ll give it a 6.0. | ||||||

| Final Score | 6.0 | ||||||

Additional Resources

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Vivitar_35ES

http://mattsclassiccameras.com/rangefinders-compacts/vivitar-35es/

http://www.35mmc.com/21/05/2016/vivitar-35es-review/

http://photo.net/classic-cameras-forum/00RmYh

http://35mm-compact.com/compact/vivitar35es.htm (French language)

http://feuerbacher.de/Mick/photo/repair/KonicaAutoS3/KonicaAutoS3.html

It’s unfortunate that you discredit your review by passing off the oft-repeated street lore as factual that Cosina origins provided the common basis for the Auto S3, Minolta Hi-Matic 7SII, Vivitar 35ES, Revue 400 SE and Prinz 35 ER cameras. Here are some objective facts: Konica and Minolta are the only two camera MANUFACTURERS in this group. Vivitar, Revue and Prinz were camera retailers that used Cosina as ODM supplier. Konica originally introduced the Auto S3’s 38mm f1.8 lens in 1966 in the Auto SE model. The Auto S3 is physically smaller and lighter than these other cameras. The Auto S3 was already out of production (1973-1977) before these other cameras were even introduced to market. The Auto S3 offered unique features such it’s innovative daylight Synchro/Flash system, anodized aluminum chassis, and larger viewfinder image using separate front pair front lens group compared with these other cameras. Are you proposing that Cosina took the camera they allegedly made for Konica in 1973, designed and tooled a larger and heavier chassis and stripped out the unique features to sell to these other companies six years later? Does that make sense? What objective evidence do you have to support your contention other than repeating the same old saw that folks continue to propagate? This is a great example of how baseless rumors are spread. Show us your evidence please.

I bought a Revue 400SE on a whim and its turned out to be one of my favorite cameras, light, compact and takes great images. It took me a couple rolls to realize that the meter was off by a few stops so I have to compensate by setting the ISO accordingly (and always keeping in mind the sunny 16 guide). But other than that it works great.

I was about to write a bit of a comment but see that Mr. Fred Baker already set the record straight a year ago. Mr. Ekman… please update this piece. The internet is full of misinformation enough already. Everything Fred Baker has stated is correct. The cameras you mention are indeed related, all but the Auto S3 which is in no way related and in fact is an inspiration to the other cameras designs, having come a good number of years earlier. I challenge you to find one, tear into it and confirm this. Similar looking and functioning is as far as it goes I’m afraid in regard to the Auto S3.

Kevin Rosinbum: At this point Mr. Ekman doesn’t seem to be interested in getting the story straight. Unfortunately repeating unsupported rumors seems infinitely more compelling than getting it right. Many of the inaccuracies seem like they ought to be easy enough to correct as data simply don’t support the warmed over misinformation.

In 1968 Konica launched the trendsetting C35 series of rangefinders that swept the market in the early ‘70’s and spawned a seemingly endless number of knockoffs including several very similar cameras that Cosina made for itself (1971 Cosina Compact 35E) and camera retailers Revue, Vivitar, Porst, Argus and Prinz. Five years later in 1973, the same basic Konica C35 chassis received an upgraded shutter/lens assembly to move up market as the Auto S3 in export markets, and silver chassis C35 FD in Japanese domestic market. The ‘FD’ (Flashmatic/Deluxe) moniker acknowledged inclusion of Konica’s advanced daylight Synchro/Flash system and upgraded 38mm lens from the 1966 Auto SE. Konica retired the Auto S3 in 1977.

In 1978 Cosina launched its Auto S3 clones that it again sold to camera retailers Revue, Vivitar and Prinz. The Cosina clones stripped out some of the features of the Konica such as the advanced daylight Synchro/Flash system with dual needle meter, anodized aluminum caps, PC connection, Konica’s larger viewfinder with separate pair front lens group and waisted film roller on the back cover and packaged their clones in a slightly larger chassis that gained 55 grams of weight. Cosina also positioned the aperture blades in front of the shutter opposed to the Konica’s aperture blades behind the shutter.

Mr. Eckman would have us believe that Cosina built the Auto S3 for Konica in 1973 and after Konica retired the camera in 1977, re-tooled the chassis and reconfigured components to make a larger, heavier camera with a lot less features to sell it to camera retailers Vivitar, Revue and Prinz in 1978. (The Vivitar, Revue and Prinz cameras were clearly the same camera built by Cosina who served as their ODM camera manufacturer.)

The facts and the timeline simply don’t support Mr. Eckman’s narrative.

I enjoy reading comments relating to lenses and cameras. I am a senior, 85 in August 2021, and have a small collection of 35mm cameras. Due to being on virus lockdown here in NSW, Australia, with little to do, I searched and found a few forgotten cameras and one lens. The lens was a Vivitar. I have no memory of buying or using this lens with the rear fitting suitable for my Nikon 90X camera body. Called a 70-210mm 1:4.5 Auto Focus Zoom. It is in beautiful condition, little or no scratches on link to camera. I checked the long list of Vivitar lenses on line. Nothing showed to help. I contacted the Vivitar company last week and received a reply. The new owners do not work in cameras. They referred me (I have done this today) to Polaroid, who they say made Vivitar lens and keep a section called ‘old Polaroid’. Nothing I have read in the history of Vivitar mention Polaroid. I await a reply from old Polaroid. Maybe someone who reads your posts might know something of my mystery lens? I have not used it with my Nikon yet. But have a roll of negs waiting in the fridge for Spring or Summer. Thank you for reading my email. Vince Morrison Ps Can I be notified of any contacts relating to my Lens? If not I will try and keep up with your posts.

Vincent, there were a huge number of Vivitar branded 70-210mm zoom lenses made from the 70s through the 90s in a variety of mounts. Their Series One zooms were considered then (and still today) to be one of the first truly excellent third party zooms made. The lens went through a huge number of variations, with production outsourced by a number of companies. Your auto focus model is obviously a later version as all the first ones were manual focus only. I doubt there is anything truly special or rare about your lens, but most likely it is like all the others in the series and will deliver good to excellent results.