This is a Miranda D 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made in 1960 by Miranda Camera K.K. Although made in Japan, around the time this model was current, most Miranda cameras were not sold in the Japanese domestic market. This camera was most likely sold in the United States by a company called Allied Impex Corp, or AIC for short. Miranda cameras had some pretty ambitious features like interchangeable viewfinders and a dual bayonet / 44mm lens mount. Early Mirandas like the model D were generally well built, but later models developed a reputation as having inconsistent build quality. The Miranda D was likely not in production for very long as Miranda was in the habit of continually evolving it’s models with new features, so this model was quickly superseded by the DR in 1961 and the F in 1963.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens Mount: Miranda Bayonet and 44mm Screw Mounts

Lenses: 50mm f/1.9 Soligor Auto Miranda + others

Focus: Removable SLR Prism

Shutter: Focal Plane Cloth

Speeds: B, 1 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: none

Battery: none

Flash Mount: PC M – X Sync

Weight: 891 grams (w/ lens), 633 grams (body only)

Manual: http://www.cameramanuals.org/miranda_pdf/miranda_d.pdf

How these ratings work |

Miranda SLRs were always meant to combine innovative professional features into a camera that was at a price point lower than the competition. In the early days of their company, their models were well built and performed well. In the later days, their quality control suffered which ended up bankrupting the company. The Miranda D is from that earlier era when quality control was higher. This is a really good looking camera that feels nice in your hands and with the front shutter release is very comfortable to shoot. While I can’t say that there is any specific reason why the Miranda D is any better than any other number of 60s mechanical SLRs, it certainly has nothing against it either. I really enjoyed shooting with this camera and it’s results are quite good. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for indescribable infatuation with this model | ||||||

| Final Score | 10.1 | ||||||

History

When most people think of a Japanese camera company, the first two that pop into most people’s minds are usually Nikon or Canon. For those that don’t instantly come up with the ‘big two’, other names like Olympus, Minolta, Konica, or Pentax ring a bell with most people. A name that probably wouldn’t come up if you asked this same question to 1000 people is Miranda.

Type the word “Miranda” into Google and you’ll get articles about a BBC Television show, Miranda Lambert, Miranda legal rights, some chick from ‘Sex and the City’, one of the moons of the planet Uranus, and even an open source instant message client. I went through the first 20 pages of search results, and didn’t find one mention of the Miranda camera company.

For photographers active in the 1960s and early 70s, or those who collect old cameras, the name Miranda is recognized as brand of quality cameras that had advanced features and sold at competitive prices compared to any other company out there.

Miranda cameras were never top of the line, and they didn’t outsell their competition, but they were never considered cheap either. In the 60s, their cameras were well regarded as they offered features like an interchangeable viewfinder and a soft return mirror that allowed them to compete directly with Nikon and their Nikon F camera. They were the first Japanese company to offer an eye-level pentaprism finder and one of the first companies to release a camera with a behind the mirror TTL CdS meter. Earlier Mirandas had a distinct front shutter release which was not common for Japanese SLRs. A front shutter release is beneficial over a top shutter release because it allowed for an externally linked automatic diaphragm system to stop down the lens to a chosen aperture the moment before firing the shutter. Front shutter releases also require slightly less force, which reduces the risk of camera shake when firing the shutter.

Another Miranda exclusive was their dual lens mount which had both a bayonet mount for Miranda’s own bayonet lenses, and a 44mm threaded mount which was designed for a series of adapters which allowed the use of many other brands and sizes of lenses. The body of all Miranda cameras was relatively narrow which allowed them to accept adapters for nearly every competing lens mount, while still retaining the ability to focus to infinity. This was done in an effort to attract customers who could use their existing lenses, rather than have to start over with an all new incompatible mount.

So, what went wrong? Other than lenses, the Miranda camera company made most of their parts in-house without outsourcing them to other companies. They preferred to keep as much of the manufacturing to themselves and did things at their own pace. Since Miranda cameras were never top sellers, it wasn’t necessary to have huge assembly lines that would churn out thousands of cameras a day.

Miranda weren’t a very diverse company. Although the company made many variants of the Miranda SLR, they didn’t make any other kind of camera until the very end of the company’s existence. In their first two decades, you only bought a Miranda if you were in the market for a 35mm SLR. They finally released a rangefinder in the early 70s, but this was near the end of the popularity of rangefinders.

Miranda stuck to their principles when most everyone else was outsourcing, or looking for bigger and faster ways to make things. This was fine in an era when SLRs were still a niche market, but by the early 1970s when the SLR became the preferred style of camera for professional and amateur photographers, they couldn’t keep up. Making matters worse, more and more cameras were offering electronic shutters, auto exposure modes, and smaller bodies, all things Miranda had little experience with. In 1975, Miranda would release the dx-7 which was their first small bodied fixed prism SLR with an electronic shutter, but it didn’t sell well, it was too little, too late. In less than 2 years after the dx-7s release, the company had gone bankrupt.

The Miranda Camera Corporation was founded in 1946 as Orion Seiki Sangyō Y.K. In English, this translates to Orion Precision Products Industries Co., Ltd. Orion didn’t start out making cameras directly, rather their first products were camera related items such as couplers which allowed Contax/Nikon lenses to be used on Leica screw mount cameras. They also released a number of other camera related products such as bellows and Mirax reflex housings.

Orion’s first attempt at making it’s own camera was the Phoenix SLR prototype from 1954. This prototype was developed over the period of several years and was only shown to the press as a promotional product designed to gain funding for future camera products.

By 1955, Orion was ready to release a production version of the Phoenix, but due to a trademark dispute they had to come up with a different name. They decided to call their new SLR camera the Orion Miranda T. The Miranda T is notable as being the first Japanese SLR with a pentaprism finder. The German company Zeiss Ikon, released the Contax S in 1949 which was the world’s first SLR with a pentaprism finder. Prior to this, all SLR cameras had a waist level viewfinder in which the photographer would flip open a lid on top of the camera and peer down into the body to compose their image.

In an effort to avoid confusion between Orion’s previous camera related products and their new Miranda T SLR, the company completely renamed itself Miranda Camera K.K. in 1957, a name which they kept throughout the remainder of the company’s existence.

In the late 1950s, the SLR camera market was still pretty small. The most common types of cameras sold were rangefinder or viewfinder cameras. Professional photographers would gravitate towards TLR cameras that were easier to use and had better optics. Miranda was the only company in the world at this time who strictly made SLR cameras. While this proved to be beneficial as they were able to put all of their focus on making quality cameras with great features, it proved to be the downfall of the company.

In the late 50s Miranda formed a very strong relationship with an American import company called Allied Impex Corporation (AIC). For a reason that I was never able to discover online, in the summer of 1959 Miranda stopped all Japanese domestic sales and all sales were export only to Europe and the United States. Miranda returned to the Japanese market in the fall of 1964 but continued to be heavily influenced by AIC, eventually being acquired by AIC by the end of the decade.

Edit: After typing the previous paragraph, I discovered an interesting letter on an archived Geocities website called “Bill’s Miranda Camera Page”. The letter is from a man named Lee Mannheimer who worked for AIC from 1969 – 1976. In the letter, Mr. Mannheimer recalls his time there and offers his version of the history which partially explains why the company failed.

The letter was likely written in the late 1990s or early 2000s, and Mr. Mannheimer acknowledges that his memory was a bit fuzzy, but he goes on to explain his version of the company’s history while he worked there.

At one point in the letter, he says:

WHEN THE COMPANY WENT PUBLIC THEY (AIC) HAD THE MONEY TO ACQUIRE THE OWNERSHIP OF THE MIRANDA CAMERA FACTORY IN JAPAN. SHORTLY THEREAFTER THE JAPANESE GOVERNMENT PASSED A LAW OUTLAWING ALL FOREIGN OWNERSHIP OF JAPANESE COMPANIES. RALPH (Ralph Lowenstein, a German Jew who was one of the founders of AIC) MOVED TO JAPAN TO MANAGE THE FACTORY. THIS WAS THE BEGINNING OF THE END FOR MIRANDA AS RALPH DID NOT UNDERSTAND THE JAPANESE CULTURE AND BROUGHT WITH HIM THE GERMAN ATTITUDE THAT HE WAS THE BOSS AND THEY WERE THE WORKERS.

Now, in Mr. Mannheimer’s letter, he doesn’t go over specific dates of when these things happened as they all seemed to occur prior to him working there in 1969. Some other websites state that AIC didn’t officially take over Miranda until later in the 1960s which would not explain why they stopped selling cameras in Japan around 1959. But his comment above about AIC buying the rights to Miranda, and that Japanese law forbade foreign ownership of Japanese companies, perhaps explains why Miranda cameras were built for export only and not sold domestically. Perhaps there was some loophole in the law that said that a foreign company could own a Japanese company, but it’s products could not be sold there.

He then goes on to say that one of AIC’s owners, Ralph Lowenstein, moved to Japan to run the company which could possibly explain how Miranda would have once again begun to sell it’s products in Japan.

Of course, this explanation could just be me reading between lines and interpreting a story that’s not even true. In either case, it is unlikely anyone will ever come up with a better explanation as the history of the entire Miranda camera is quite scarce already.

The Miranda D being reviewed in this article first went on sale in December, 1960. The letter “D” might suggest this was the fourth Miranda following models A, B, and C, and although that’s partially true, Miranda had a habit of continually revising their designs and releasing new models with different names. According to the Miranda Model Detail table at mirandacamera.com, the D was the 11th or 12th Miranda camera. I say 11th or 12th because there were Miranda D’s made with two different body shapes, an earlier design with sharp corners like the image of the Miranda T above, and a later design with rounded corners, like the model being reviewed here. There was also a variant of the D called the “DR” which had a red dot in the center of the exposure counter and a microprism focus aide on the ground glass.

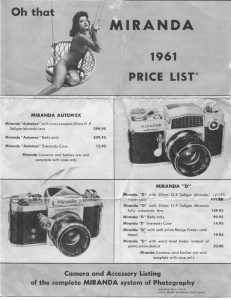

According to the 1961 Price List to the right, the Miranda D sold without a lens for $99.95. With the externally coupled Soligor f/1.9 lens, the price rose to $159.95. When adjusted for inflation, that’s $804 and $1287 respectively, today. Certainly, the Miranda D was not an inexpensive camera!

Miranda would remain profitable through most of the 1960s. Their reputation as an innovative company with features only available on more expensive cameras made them appealing to advanced amateur photographers. After 1967 however, their quality control started to suffer which caused their reputation to nose dive. The company would limp into the 1970s and would struggle to compete with their competitors who were releasing smaller, and more intelligent cameras capable of auto exposure and had other advanced features. By 1975, the company would be completely bankrupt.

After Miranda went bankrupt, the “Miranda” name was reused in the late 80s by a completely unrelated company who made a cheap line of point and shoot cameras. It’s also worth mentioning that there was also an unrelated Japanese company also called Orion Seiki who made a line of folding cameras in the 1950s that predates the Orion/Miranda company. The presence of this company could have also contributed to why the Orion Camera Company changed it’s name to Miranda but I never found any conclusive evidence during my research.

Today, Miranda cameras have a loyal following among camera collectors and people who still like to shoot vintage cameras. Since their quality control was questionable in their later years, it can be difficult to find them in perfect working condition, but with a little bit of patience, they can still be used. Like any vintage camera, they are prone to light leaks and slow shutters, but once they’re cleaned up, they are just as good of an example of a 1960s SLR as anything else out there.

Many of the features that made them popular in the 1960s such as the interchangeable prism, front shutter release button, and dual lens mount still make them appealing today because of their uniqueness. The most popular later models were the Sensorex and Sensomat, so they’re the easiest and cheapest to find. Of the early models, the Miranda D sold fairly well too, so they show up for sale on the used market semi-regularly. The oldest Mirandas, specifically the original Orion Miranda T are extremely collectible and sell for outrageous prices.

My Thoughts

“Moby Dick”, tells the story of Captain Ahab’s relentless pursuit of a white whale who he had crossed paths with on a previous voyage which destroyed his ship and crippled his legs. In the years that would follow, Ahab would become obsessed with getting his revenge on the whale, only to miss the opportunity time and time again.

Moby Dick, or ‘the white whale’ represented an obsession to triumph at any cost, over a foe which had repeatedly taunted him. For many of us, we have our own ‘white whales’ which can be anything that conjures up images of ultimate dread, of ill-fated unfinished business, and of hopeless, lost causes and predestined disasters.

My ‘white whale’ is the Miranda SLR. In fact, the last two words of the previous paragraph ‘predestined disaster’, accurately sum up my quest of making it through a full roll of film using a Miranda SLR.

How did this come to be? I have no idea.

In the early years of my re-discovery of film cameras, I picked up a Miranda Sensomat and found it to be a handsome and interesting camera. I loved the look and the feel of the camera. It was the first SLR I had ever used with a front shutter release and a removable prism.

I loaded in my first roll of film and got an entire roll of images like the one to the left. As it turns out, that first Miranda was missing the film pressure plate. Despite loading the film correctly, without a pressure plate, the film has an ever so slight curl as it passes through the focal plane meaning parts of the image will be badly out of focus. The image to the left almost looks like I was going for some type of tilt-shift effect, but I assure you I was not. Every image from that roll turned out like this. I did not realize what had gone wrong until after getting the film back.

I found a junk Miranda Sensomat and took the pressure plate from that one and put it on the first Miranda and tried again. Some images from this second roll actually came out quite nice, but then about halfway through the roll, the camera decided that it wanted to have shutter issues. More than half the roll looked like the image to the right where the whole right side of the frame was entirely black. This generally means the second curtain is traveling too fast and not separating from the first curtain during it’s travel. Normally this could happen at only certain shutter speeds, but in this Sensomat, it was unpredictable and I knew I couldn’t trust this camera. Oh, and just for the hell of it, the reflex mirror on this camera would randomly get stuck in the up position after taking an image. It wouldn’t have a negative impact on the image, but I would have to remove the lens and push it back down with my finger each time this would happen. You know, just for fun!

I began my search for a different Miranda, and this time ended up with a Sensorex. At first, the meter was dead on this camera and I figured I would use it entirely meterless, but upon a very liberal cleaning of the battery compartment with some warm water and baking soda, I actually got the meter to work. I loaded in some film and went shooting and got a whole roll like the one to the left. As it turns out, the meter was off, way off. The image to the left is actually one of the better images from that roll. Almost all of them were completely muddy and underexposed by at least 3 stops. As an added bonus, the film compartment latch decided to come undone twice while shooting with that roll, so some of the images were ‘double ruined’ by light leaks.

Okay, so the meter is off, I can just go back to my original plan of shooting with this camera and not rely on the meter. I also resolved the door latch problem by ever so slightly bending the door back to it’s original position. It turns out this camera must have had the door damaged at some point in the past which caused the door to not latch correctly. So, I shot a second roll in this camera using Sunny 16 and hey, look at that bus! More light leaks and another shutter issue! At least what you can see of the bus looks properly in focus, and properly exposed. Too bad nearly the entire roll exhibited signs like this.

Miranda number 3 (4 if you count the parts one I used to take the film pressure plate for the first Miranda) came my way and this was another Sensorex. Like the other one, the battery compartment had some corrosion, but a bit of cleaning got it to respond to light. I was happy to see the needle move, but I knew better. I wasn’t going to trust it. Okay, this one seemed to not have any issues. As best as I could tell, the shutter wasn’t capping, the film pressure plate was in place, the mirror wasn’t sticking in the up position, and I wasn’t going to trust the meter. What could go wrong?

FML. I can’t explain this one. Like the third image above, this roll was grotesquely underexposed. The blue cast in the image was likely caused by the lab trying to pull as much detail out of the image as possible. What a shame too, because this would have been a nice image.

To add insult to injury, I actually dropped this Miranda on a concrete bathroom floor putting a big ole’ dent in the prism. It’s worth mentioning that the images I shot before and after dropping it were underexposed like this, so my carelessness was not the cause of the issue.

So, here I am today. I am 0 for 5 shooting 3 different Mirandas. I don’t know why I bother. Like I said though, this is my white whale. Miranda SLRs taunt me and I must overcome. I have ill-fated unfinished business with them.

I should also mention that in my quest to get a good one, I keep accumulating nice Miranda glass. I have two 28mms, three 50mms, a 200mm, and a 2x Soligor teleconvertor.

So, as fate would have it, I wound up with this Miranda D. It is the oldest of any Miranda I’ve owned, and while normally you would think that an older model would be more likely to exhibit problems, there was a well known drop in quality control at Miranda by the late 60s. Perhaps this earlier model from 1960 was from a better era. Maybe it would be built better, and maybe it would work properly.

Maybe.

In terms of usage, the Miranda D is a very comfortable camera with excellent ergonomics and a very reasonable weight. With the Miranda 50/1.8 lens attached, the camera weighs in at 837 grams, this is heavier than a Pentax Sv with Super Takumar 55/1.8 at 803 grams, but lighter than a Nikkormat FTn with Nikkor 50/1.4, an Ihagee Exakta with Zeiss Pancolar, and a Leica M3 with Summicron 50/2 all weighing in at 1061 grams, 908 grams, and 881 grams respectively.

The front shutter release is in a logical position for your right index finger to easily locate. The Miranda D relied on an external linkage to stop down the lens prior to shooting, so if you have a lens like the one pictured to the left, the shutter release is a little farther forward from the camera to accommodate the linkage. You can optionally use this camera with later Miranda lenses but the auto stop down feature will not work, you must do it manually.

The interchangeable viewfinder allows for use as a waist level camera, but unlike other cameras like the Ihagee Exakta or KMZ Start, the focusing screen stays in the camera, so the camera can be used without any viewfinder attached like in the image to the right. Miranda did make an optional waist level finder for the camera, but it doesn’t have it’s own ground glass, it’s just a shield with a magnifying glass.

Regardless of which viewfinder you are using, the focusing screen has no other focus aides like a microprism collar or split image rangefinder. It is just a flat piece of ground glass with a circular Fresnel pattern to improve brightness. While this sounds primitive, I found that it wasn’t any harder to focus this camera than any other SLR of the era.

It is clear, more than 50 years after these cameras were designed, that the people who ran Miranda cared about design and functionality. These are very handsome and well thought out cameras. The people working for Miranda very much wanted people to consider them a top tier maker, and for a while they succeeded. I think that the massive success of other Japanese makers was too much for this small company to stay competitive, and a combination of mismanagement, and cost cutting measures were taken, which caused the reliability of later models to suffer, which ruined the company’s reputation.

So now that I’ve depressed you with the history of a failed company and my 5 unsuccessful attempts at shooting one, lets see some results from this one!

My Results

While many of you might see the Miranda D as just another mechanical 1960s SLR, my prior history with the brand caused me a bit of anxiety when I received my scans back. Would the curse live on with any other number of mechanical maladies that have previously plauged me, or would I be graced with a roll of properly exposed shots?

As you can see, I was quite elated to see these images. Yes, a few pictures were ruined because of my boneheadedness opened the camera near the end of the roll before I had rewound it, but I cannot blame the camera for that.

These images were all shot using Sunny 16 with a combination of Miranda 50/1.8 and 28/2.8 lenses. The f/1.9 lens pictured with the camera above was the one that came with it, but it has an issue with the aperture iris and it won’t stop down. So, while you could technically say the curse is somewhat alive in the fact that the included lens was frozen, and I still didn’t make it through a whole 24 exposure roll without ruining 3-4 images, I can wholeheartedly say that this is my first true success with a Miranda SLR.

There are likely those of you who see no appeal to Miranda cameras, and I honestly don’t blame you. There really isn’t any one thing that makes them better than anything else of the era. My affinity for them is illogical, but every time I hold one, I can’t help but marvel at the beauty of them. Of the 3 Mirandas still in my collection, a Sensomat, Sensorex and this Miranda D, this camera is the oldest, and in my opinion, the best looking. Look at the image to the right of 4 of my favorite 1960s mechanical SLRs. While I will always be a “Nikon” guy, their design was more purposeful, rather than beautiful.

Miranda may have had a sketchy reputation over the years, but when they work, they work well. Their lenses were great, and judging by my Sunny 16 approximation, it seems the shutter speed is accurate.

I will definitely use this camera again, but will do so with caution as “the curse” could very well come back later on down the road.

Additional Resources

http://web.archive.org/web/20091021085509/http://geocities.com/bill14210/index.html

http://web.archive.org/web/20020619015052/http://www.246.ne.jp/~honmage/MSJ_html/type.html

https://www.cameraquest.com/orion.htm

Thanks for perhaps the most scholarly Miranda information on the internet. And for the article how the ads were made. I bought a Miranda DR back in about 1962 (my age was 15) when I think the list price was $169 and Village Camera in Oak Park, IL sold it to me for $118. I used that camera for 25 years and it traveled the world with me including when in the military. I eventually succumbed to a Canon EOS-650 in 1987. Our family had a Voigtlander rangefinder where I first got hooked on 35mm. But I was enthralled by the idea of SLR’s. I bought Kowaflex (I think the first Kowa SLR and it had a non-interchangeable lens and add-on telephoto and wide angle adapters) and thought I was pretty happy. Then a friend bought and showed me a Miranda DR and that was that. Of course, a Nikon F was the dream, but hopelessly too expensive for me. And I REALLY wanted a removable viewfinder. Therefore the Miranda DR. I still think it was the best camera VALUE of the era. I added a couple of off brand lenses one with a bayonet adapter and one I would screw in (always on a teenager’s tight budget). Then an “Ultrablitz Monojet SP” flash which I also felt was amazing. I still have that camera and it still seems to work fine. When I got the Canon EOS-650 with its zoom lens included in the kit, I took comparison photos with the Miranda and its 50mm 1.9 lens. The Miranda’s lens was noticeably sharper. Believe it or not, I never saw one of those racy Miranda ads until AFTER buying the camera. It was the woman in the hammock. Pretty erotic stuff for a teenager in the 1960’s when you mainly found nudity only of African native women in every other month of National Geographic.

Charles, I am glad you were happy with the review and my short article on the Miranda ads! I definitely agree with you that Miranda offered the best value at the time and had I been an active photographer at the time, there’s a very good chance I would have wound up with one myself! Ever since handling my first Sensorex, I was hooked, and it wasn’t until I got this Miranda D from this article, that I had a perfectly working one. I also have an excellent Miranda A that works great too, but I’ve never reviewed it as it’s so similar to the D, I don’t know what else I could say about it.

Great article Mike! I developed a Miranda fixation a couple of years ago, when ordering an AF film slr on Amazon. I bought a Canon Rebel 2000, and the seller was also offering Miranda Sensorex w 50mm 1.9 lens, for $60. The camera looked unique, and clean, so I thought “why not?” I wound up returning the Rebel 2000, but kept the Miranda! It’s in perfect shape, the meter works (not sure how well), and all the shutter speeds sound accurate. Fast-forward a few years, and I have that Sensorex, two Sensorex II’s, a Sensomat, an Automex and an FV! Oh, and two VERY dead DX-3’s (those are my White Whale. Why else would I buy two?!).

It’s really funny that you talk of ‘white whales’. I’m only starting in my 35mm film journey, and so have no such proper beasts, but there’s already a few in my collection that could qualify: an interchangeable-lens Werra (I’m technically on my third dead one); a Kowa SET R (in no small part due to your wonderful review of the model, and am also in my third one); but perhaps most especially the FOCA Universel R, a camera that I have ardently desired for a year – when I could finally afford one, it was in almost immaculate condition, but unfortunately the shutter is stuck, and I very much dread opening it up for repair (the FOCA user manual starts by boasting that the camera is ‘built from 571 individual pieces’, damn!).

I really, really want to have at least one of each working by the end of this year. Your reviews are a great source of inspiration, Mike, and I appreciate them very much. Thanks.

Andreas, you certainly have not made it easy on yourself, choosing cameras like the SET-R and Werra as they’re all known for being finnicky. I actually have shot a Werra recently and plan on doing a review for it later this year, so hopefully you’ll be interested in that once it posts.

As for Miranda, my bad luck with them has continued in the time since my last Miranda review. The most notable example was that I really wanted to shoot the dx-3, which I knew had a bad reputation for reliability even by Miranda standards. I had one before that didnt work and a friend who had one that only would fire at a single shutter speed. I stumbled upon a lot of 7 Miranda dx-3s, all in their original box and all in nearly perfect cosmetic condition. I thought had hit the jackpot as out of 7, some should work right?

Nope. Not. A. Single. One.

The closest I came was one of them where the shutter would fire, the meter was a bit finnicky, but did respond to changes in light, and had a working display. I loaded film into it, only to discover that the film transport was damaged. I would wind on the camera and fire the shutter, but the same piece of film was being exposed over and over again. I tried taking the base plate off to see if there was any obvious problems I could resolve and I couldn’t figure it out. So yeah, 0 for 7 on that model.

I still like Mirandas though, and while I know my limited experience can’t possibly be the rule for all of them, I seem to have better luck with the older ones. I have both a Miranda A and D, and both work great. The D seems to show up on eBay often and seem to pre-date a time when their quality control took a nosedive.

Good luck with them and your other “white whales”! 🙂

I also have a sweet spot for Mirandas, mostly because my very first “proper” camera was my Dad’s hand-me-down F, which had the normal 50mm and an aftermarket preset 28mm lens. The only trouble it ever gave me was the leatherette tending to peel off – it was very reliable and most of my photo work went into our high school yearbook. At some point, I got rid of it and my poor memory can’t recall how. Anyway, I later got the “bug” for them and at one point had quite a collection. The later models were indeed more troublesome, but only insofar as the electronics went. Right now, I still have a pristine DR that works well along with a ton of lenses, most of which need diaphragms cleaning. I don’t shoot much 35mm these days (MF is my preference), but I would rather use any of my Mirandas over the venerable Nikon F, mostly for the same reasons you mention – they are beautiful and really enjoyable to hold. The front shutter release was always one of their best features, IMHO, as it tends to reduce camera shake.

Sounds like you and I would get along quite nicely in our own two-person Miranda fan club. In all seriousness, it seems that anyone I’ve encountered whose had a chance to use one of the older models, like your DR or my D (I also have an A I’ve never formally reviewed) think fondly of them. It seems anyone who doesn’t care for them only remmebers the later models. Whether you shoot them or keep them on a shelf though, they certainly are pretty! Thanks for the comment!