This the Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127 camera made in the United States around 1958. As the name implies, it uses 127 roll film and takes twelve 4cm x 4cm exposures. Although a simple box camera with a fixed focus, a single speed shutter, and very little manual control, it was one of the first cameras in the world to have full automatic exposure. Simply set the camera to ‘EE’ mode and the selenium cell controls the aperture automatically according to the available light. A red flag would appear in the huge viewfinder to notify the photographer that there is not enough available light, but when the red flag goes away, the camera is ready to go. As simple as this sounds, it worked incredibly well and allowed the camera to work in a variety of outdoor and well lit indoor lighting conditions. The shutter is flash synchronized and when paired with an accessory flash, the camera can be used indoors as well. Unlike most other simple box cameras of the day, the attractive body was all metal rather than plastic. The camera is very sturdy and does not give the appearance of a cheap camera.

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (twelve 4cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Film Type: 127 Roll Film (twelve 4cm x 4cm exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown focal length (probably around ~60mm), aperture range f/8 – f/45, 2 elements, coated

Focus: Fixed Focus (~7 feet to Infinity)

Type: Brilliant Viewfinder

Shutter: Single Speed Metal Blade

Speeds: Approximately 1/50th sec

Exposure Meter: Selenium cell automatic exposure with manual override

Battery: None

Weight: 613 grams

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/BellHowellEE127Manual.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Bell & Howell is the rare exception of a box camera that’s unlike any other. It has a beautiful, all metal body, a large and gloriously bright viewfinder, and it even has auto exposure. Sure, it takes hard to find 127 film, but if you are willing to go through whatever it takes to get some film this camera is absolutely worth it. Shooting with it is fun. While at first it might seem like a limited camera, if you are able to work within it’s limits, you’ll find that it is also a very capable camera. I don’t know that there’s many box cameras I would ever use more than once, or even look forward to using again, but this is one. These things are plentiful on eBay for dirt cheap, and if you are reading this, I wholeheartedly encourage you to give one a chance! | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 30% | |

| Bonus | +1 for an indescribable fun factor while shooting with it. | ||||||

| Final Score | 8.8 | ||||||

History

The Bell & Howell Company was incorporated on February 17, 1907 by Donald J. Bell, a projectionist, and Albert S. Howell as a maker of cinematic film projectors and cameras. They were originally based out of Wheeling, Illinois which is a far northwest suburb of Chicago.

In their early years, their primary products were 35mm cinema projectors for the film industry. Their earliest products sold very well and were popular in the early 20th century in Hollywood. As wartime came and went, they would produce a variety of 16mm film products for the US military. In 1934, they released the first amateur 8mm film camera which allowed daylight film loading. Throughout the years, Bell & Howell has made a variety of their own film related products along with products from the computer and audio industries.

Although Bell & Howell was not known for many still film cameras, their most ambitious was the Foton from 1948. A very elegant camera, the Foton was a high spec 35mm focal plane rangefinder with an interchangeable lens mount. The shutter was a unique all metal design that traveled vertically, similar to that of the original Contax camera. It had a unique focus helical that was part of the body of the camera, rather than the lens, meaning that the lenses were very compact. It’s most advanced feature was a spring loaded film advance that could continuously shoot up to 6 frames per second. This was an unheard of feature at the time, and as reference, 6 frames per second would still be considered good for modern digital SLRs today. Initially sold for $700 which was extraordinarily expensive for the late 40s, the camera only sold in small numbers. Today, the Bell & Howell Foton is extremely rare, and one of the more desirable cameras for collectors. When one does come up for sale, they often go for extremely high prices.

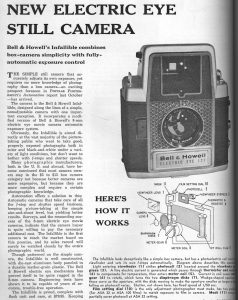

The Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127 was possibly the last still film camera that the company ever made. It had a list price of $79.95 and included an accessory flashgun and leatherette case. Although a pretty basic camera, it was solidly built with a revolutionary auto exposure system that was billed as having an “Infallible Electric Eye”. While the word infallible might be a bit of a stretch, it managed to accurately expose images without the use of batteries or any electricity whatsoever. An amazing feat considering the era.

From 1961 through 1976, Bell & Howell had a distribution agreement with Canon and would sell rebadged versions of popular Canon SLR and rangefinder models. In 1979, the company sold a modified version of the Apple II computer specifically for educational use.

Over the years, Bell & Howell dabbled in a variety of industries, but by the early 2000s, they decided to focus solely on their Information Technology business and all of their imaging related assets were sold to Kodak. The company still exists today making products for the postal and information sorting industry.

My Thoughts

While I generally have no one to blame but myself for the cameras in my collection, I can truly say that the reason I picked up this Bell & Howell EE 127 was entirely based on my friend Adam Paul’s suggestion. His website, Quirky Guy with a Camera has reviews of old cameras like mine, and while each of us often take the road less traveled, Adam takes that road and travels it using cameras that require film that hasn’t been made in decades. He cuts down his own film from larger stock and makes all new film using types that were never available when those cameras were current. Want to shoot a Kodak Bantam with 828 Kodak Ektar 100? He’s done it!

He had been talking about 127 cameras and I mentioned to him that I had a Detrola Type E that I had been meaning try out, so without hesitation, he mailed me two rolls of 127, one fresh, and one that he had cut himself. Before I had a chance to ever try out the Detrola, he started talking about this other 127 box camera and after seeing some pictures of it, I knew I had to add one to my collection.

So the search began for a comparable EE 127. The search didn’t take long as they are plentiful on eBay. I picked up a very nice one in it’s original case with shipping for under $20. I was delighted that when the camera arrived, it was in near mint condition and everything seemed to work, even the meter. Selenium meters are very unpredictable. I have many that are completely dead or so inaccurate that you can’t use them. Since this camera’s entire exposure system requires the meter to work, I was nervous that it might be a dud, but thankfully it wasn’t.

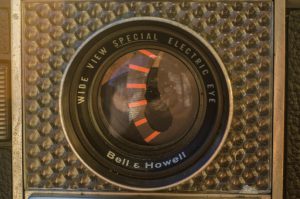

One thing I should point out that fooled both Adam and I is that the large “honeycomb” plastic grille that completely surrounds the taking lens is not actually the meter. The photocell for the meter is located inside of the huge viewfinder. If you shine a flashlight into this honeycomb area, the meter doesn’t respond. Move your flashlight into the viewfinder and it does. I mention this in case this tricks someone else into thinking that perhaps their EE has a dead meter. Try shining a light into the viewfinder, or just take the entire camera out into direct sunlight and you should see it move.

Perhaps the most interesting design element of this camera is in how the auto exposure works. On most cameras with a selenium meter, the meter moves a needle that points to a corresponding light value on a chart. Bell & Howell took this concept and rather than giving it a moving needle, they connected the meter to the actual lens itself. Inside of the lens, instead of a needle, there is a metal plate with a slit running through the middle of it that starts off small and gets wider towards the end. This moving plate has painted red lines on it that are visible in the image to the left. When the selenium cell detects light, it moves this metal plate into a position that lines up the lens with a spot on the metal plate with a corresponding opening. The more light the meter detects, the narrower the opening. As light decreases, the metal plate moves in the opposite direction allowing more light to enter the lens.

They didn’t stop there. This metal plate also connects to a red flag inside of the viewfinder that will be visible when there is not enough light for the camera to exposure the film properly. Once enough light is detected, this red flag disappears, showing a clear green tab which indicates that it is OK to take the image. It is worth noting that this red flag can only indicate underexposure. There is no way for the camera to let you know that you will overexpose the image.

The camera does have double exposure prevention which locks the shutter release after making an exposure. Advancing the film is done by a knob on the bottom of the camera and once you advance the film, you hear a click which is the double exposure prevention being disengaged.

Before you can use the camera, you need to load film into it and this is one aspect in which the EE 127 shows it’s box camera roots. Like many box cameras, the film compartment is it’s own separate compartment that must be entirely removed from the camera before loading. When releasing the lock on the bottom of the camera, the entire bottom plate and film compartment comes out of the camera in one piece. This makes film loading incredibly easy, but also does a really good job of keeping the film compartment light tight. There are no foam or yarn light seals that you need to worry about on this camera. Aside from physical damage to the body, there is little way in which this camera can have a light leak.

Once you have film loaded into the camera, it is time to use it. The EE 127 is a very basic camera that was designed for novices who didn’t want to be concerned with things like shutter speed or aperture. The whole process is pretty simple, but even the simplest cameras usually have one or two simple settings, and the EE 127 is no exception.

There are only two things you can change on this camera, the first of which is a black dial on the right side of the viewfinder. This dial has two marks on it, a red triangle and a white circle.

There are only two things you can change on this camera, the first of which is a black dial on the right side of the viewfinder. This dial has two marks on it, a red triangle and a white circle.

The Red Triangle moves an additional filter in front of the light meter inside of the viewfinder and was designed for color films like Kodacolor or Ektachrome. This setting corresponds to roughly a film speed of ASA 25- 32.

The White Circle removes the filter in front of the light meter and is for faster Black & White films like Verichrome Pan, and other Black & White Panchromatic film. This setting corresponds to roughly a film speed of ASA 80 – 100.

These two settings correspond to roughly a 2 stop difference in film speeds. Of course you don’t need to actually use any of these older films, as any 100 speed film would line up with the White Circle when shooting Sunny 16, and use the red triangle for expired film.

The only other manual setting on the camera is hidden beneath the metal “Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127” plate on the bottom front of the camera. Flip up this plate and you’ll see a slider that overrides the “Electric Eye” feature of the camera and allows you to manually adjust the aperture plate inside of the lens. Since the electric eye feature is deactivated when you manually adjust this slider, Bell & Howell designed it in a manner in which you cannot close this door if the slider is in any position other than the E/E position. This was a wise move on Bell & Howell’s part since this camera is obviously aimed at novices and it is entirely plausible that the camera could accidentally be left in manual mode.

The original purpose of this slider is for manual adjustment for flash photography, but it doubles as a manual aperture override. Since we don’t know what the actual f-values are of this camera, one could only guess at what these settings really mean, but it is safe to assume that on the far left, the aperture is at it’s smallest setting (possibly f/22 or f/16), and as you move it towards the right, it moves to it’s largest settings (probably somewhere around f/8).

For normal operation of the Electric Eye, you leave this slider in the far right position so that the yellow E|E mark lines up with the yellow arrows. For my inaugural roll of ReraPan 100, I had intended to shoot a variety of shoots in both E|E mode and by choosing one of the sliders. Sadly, I wasn’t able to stick to this plan and the entire roll was shot in E|E mode.

I have to imagine that people were pretty impressed with this camera when it was first introduced in 1958. Back then, there weren’t many options for those who didn’t know much about photography. It must have been pretty exciting at the prospect of having a camera like this that could do most of the work for them. I say “most” because as an early auto exposure camera, it can’t handle everything. In order for any camera to be “focus free” it must have a rather small aperture. Small apertures drastically reduce a camera’s ability to shoot in low light situations such as interior shots.

When purchased new, the Electric Eye 127 came with an accessory flash gun, however the electric eye is not able to measure flash exposure, so once you try to use the flash, you must take exposure measurement into your own hands, greatly reducing the simplicity of this camera. I do not know how many people who would have bought this camera for it’s electric eye feature would have also tried to use it with the flash.

Another shortcoming of the meter is that it is only capable of taking an average reading in the viewfinder, meaning that greatly backlit or frontlit scenes would be over or under exposed. This camera has no ability for +/- exposure settings and certainly couldn’t do spot metering. Still, when used under ideal conditions, the meter is surprisingly accurate. In a review in the January 1959 issue of Popular Photography, writer Gene Gaines says “…the simple automatic exposure camera does provide the considerable advantage of foolproof, easy operation for the casual amateur.”

The Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127 is a strange looking camera, but when you hold it, it’s strangely comfortable and fun to use. The textured metal body looks good and feels solidly built in your hands. Looking through the large and bright viewfinder tricks your eye because most other cameras, even modern DSLRs don’t have viewfinders this large or bright. You’re so used to seeing smaller and darker images that the EE’s viewfinder almost seems brighter than reality. The whole process of using this camera is unique and gives an indescribable level of enjoyment. This is a fun camera. It attracts attention from people on the street because it doesn’t look like anything else out there. While certainly not a high spec camera, it doesn’t need to be. It’s a shame that 127 film isn’t common anymore as I think that cameras like this would still be relevant today with the resurgence of interest in plastic Holga, Diana, and Polaroid cameras.

My Results

While shooting with old film cameras has a variety of rewarding moments, one of my favorites is when you get a camera that you knew little about beforehand, and had very little expectations for, but find yourself enjoying it more as you use it.

The Bell & Howell Electric Eye 127 was a camera that I thoroughly enjoyed while using it. Before finishing the roll, I felt like this would be a camera that I would want to come back to more than once. Even if the results weren’t the best, I thought of all the 127 cameras in my collection, this one would stand out.

Sadly, my results from my first roll weren’t the best. One of the primary factors I think was the ReraPan 100 film. This stuff is hand rolled 127 format film and is sold by B&H Photo for about $12 a roll. The product description of the film says:

…medium speed film for producing prints using a traditional black and white printing process. It exhibits a nominal sensitivity of ISO 100/21° and standard development in black and white chemistry yields a fine grain texture with even tonality.

Later in the description it warns that this film is very light sensitive and should be loaded in subdued light. I know that I loaded this film the night before shooting in a mostly dark living room, plus the EE 127 has a pretty light tight film compartment, so I don’t think that I accidentally exposed the film in any way. The description says it has a fine grain with even tonality which I don’t know if I agree with. To my eyes, the images are very grainy and harsh, plus most of the shots showed edge vignetting where the edges were considerably darker than the rest of the image. Could this be a fault in the film or how it was rolled? If this had been cut down from 120, I might believe that, but I was under the impression that ReraPan was a new film made specifically for 127 cameras so I am not sure why the edges are so much darker.

I can’t entirely blame the film though, because the camera overexposed the entire roll. Since the EE 127 has a single speed shutter, I didn’t have much in the way of control over shutter speed, so I trusted the aperture to the Electric Eye. It’s plausible that this EE 127 just isn’t up to the task of taking photos like it used to. Shutters have a tendency to slow down over time which can over expose a shot. It’s also plausible that something in the circuit for the meter is causing it to stay at a wider open setting than it should. Maybe I would have had different results with a different EE 127.

The good news is that the over exposure seemed to be consistent in every shot, so if the ReraPan is a 100 speed film, perhaps finding something around ASA 50 or even 25 might be perfectly exposed with this camera. I can also say that every single one of these shots was done on a bright sunny day. Perhaps shooting in more subdued light would have helped too.

Finally, it’s also possible that the lab had issues developing this film. I don’t mean to speak ill of Dwayne’s Photo as I usually am very pleased with the results, but this is now the second black and white roll that I’ve gotten back from them with very questionable results. The first was a roll of Ilford HP4 that I shot in my Kuribayashi Karoron. The entire roll came out harsh and muddy. The odd thing is that camera had a complete CLA, so there was no reason for it to be that bad. I took another chance with that camera with some fresh color film, and upon reviewing the results from that roll, the camera showed that it was capable of great shots.

All is not lost though, I can say that the lens shows some reasonable detail for a dual element lens. The images seem sharp and well defined, especially the one of my house. I tweaked every single one of these shots in Photoshop to curb the highlights which improved the images somewhat.

I am optimistic about what another roll of color 127 might produce in this camera. The problem of course with 127 is that it is hard to come by, plus when you do, it can be pretty expensive. It’s such a shame that I cannot quickly redeem this camera with another roll. I will definitely come back to it someday, but my backlog of other cameras to shoot is quite large and it’s going to be some time before I have another chance to shoot with this camera again.

Additional Resources

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Bell_%26_Howell_Electric_Eye_127

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Bell_%26_Howell_Electric_Eye_127