Throughout my life taking pictures, and later collecting cameras, one thing I took for granted was the fact that instant film exists. As a kid growing up in the 80s, everyone had a Polaroid camera. I didn’t know how it worked. All I knew was that you could go to the store, buy some film, stick it in the camera, press a button, and 10 seconds later, you’d have an image.

When the image popped out, I shook the image back and forth for a few seconds because that’s what everyone else did, and everyone else couldn’t be wrong right? Did I ever stop to ask myself, “why am I shaking this picture?”, or did I even bother to wonder how it worked?

No. I made my squared rectangle Polaroid images and moved on with my day.

Now that I have a fairly decent understanding of how photography works and the science of developing a print, when I think back to Polaroid cameras, I am amazed that it ever worked at all. I don’t think I will cause any controversy when I say I am often disappointed at the results of modern Polaroid Originals film as it doesn’t look like the original. We can do some pretty amazing things with technology today, so why can’t we make an instant film that works like the old stuff.

As I learn more about Edwin Land and a process he harnessed called diffusion-transfer reversal to make the first instant prints, I have to imagine that when people saw the first Polaroid Model 95 back in 1947, they likely lost their minds.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault looks back to two articles, the first is a 10 page special report from the May 1955 issue of Modern Photography that is sort of like several mini articles in one, starting with a bit of history and how the camera works, then a review of the quality of Polaroid images, including how enlargements are made, and then finally some tips on how to get better at photography with an instant film camera. The second is from May 1961 and further explores how to obtain a proper negative image from any regular Polaroid instant print.

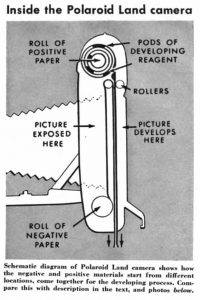

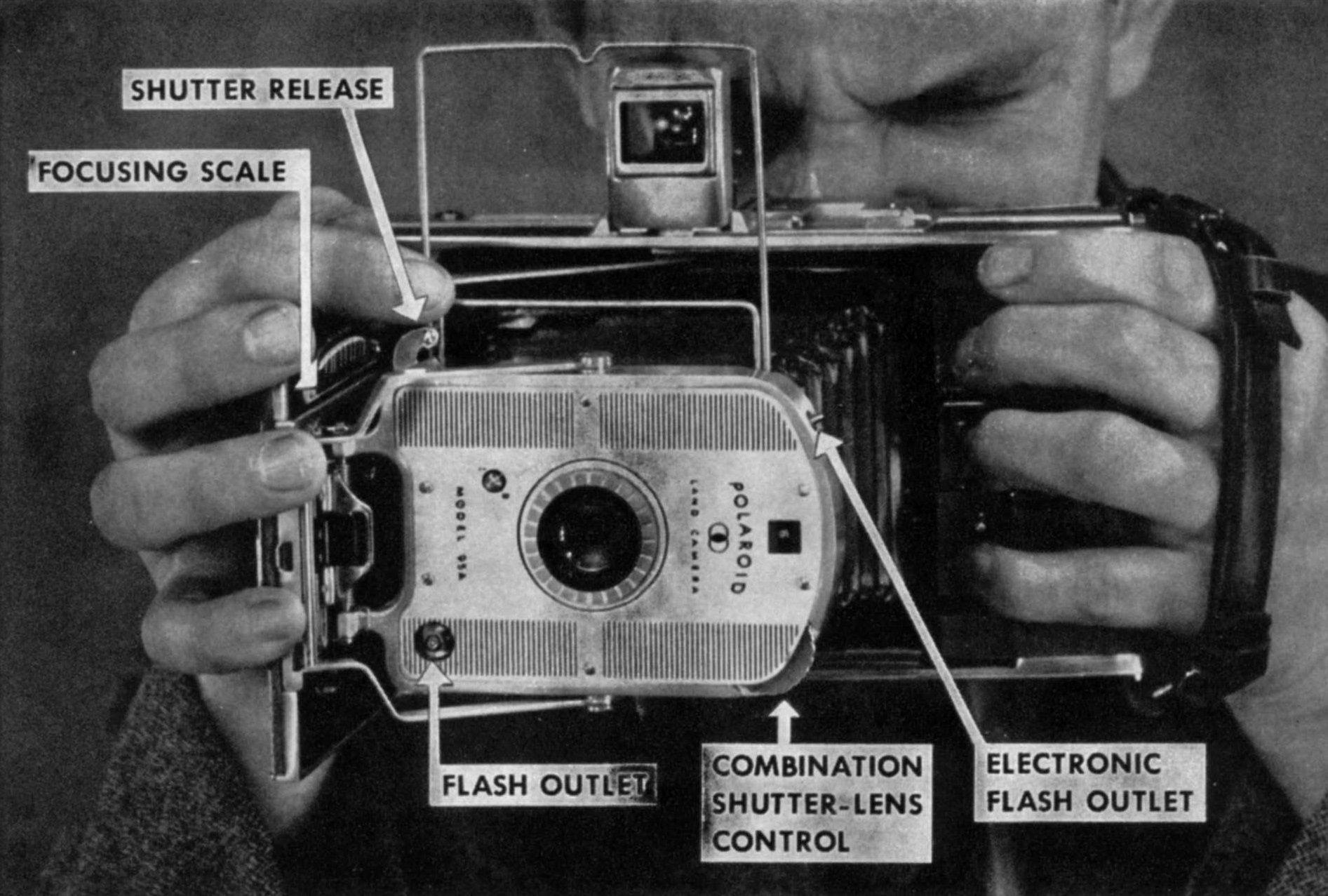

For anyone my age or younger whose only experience with Polaroid cameras was with pack film in which single sheets of film are contained within a magazine, you might be surprised to learn that the original Polaroid cameras were large folding cameras that used a special type of instant roll film in which the photographic negative and development chemicals were rolled through the camera separately. At the moment of exposure, the camera would expose light sensitive photographic film exactly like any other camera, but upon pulling the paper backed film from the camera, it would pass through two metal rollers at which point it would be pressed against a separate sheet containing the developing chemicals, which would begin the development of the image.

Earlier Polaroid film took up to a minute or more to develop an image, so the images weren’t quite “instant” but compared to the speed at which a regular camera’s film would need to be sent to a lab or home developed hours, or even days later, it was still pretty fast.

When the Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 was first introduced in 1947, it was a marvel of technology and engineering. The ability to see a print within a minute of capturing the image was momentous, something that digital camera shooters of today likely will never understand, but for all of the wizardry of the camera and it’s film, the images it made weren’t that good.

The earliest Polaroid film was orthochromatic, which means it’s not sensitive to red light. This is great for developing in a dark room, but not so good for skin tones or capturing anything with warm colors in it. Another disadvantage to early Polaroid film was that there wasn’t a good way to make enlargements, and early attempts often resulted in images with lackluster definition.

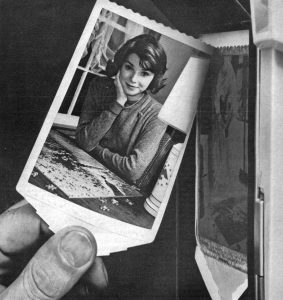

It would take a few years, but with new and faster panchromatic Polaroid film, serious photographers were now considering the camera and it’s film as skin tones were more realistic, images were sharper, and with instructions explained in the article, the original photographic negative could be more easily separated from the print and a proper enlargement made.

Getting a negative from a Polaroid image was not something that was ever officially endorsed by Polaroid as it required the use of a dark room which would allow for the camera to be opened midway through a roll of film and the image extracted and split, but once the process was mastered, it was possible. While this would qualify as a “life hack” if mentioned today, I have to imagine professional photographers that were already used to darkroom alchemy likely didn’t see this as much of an obstacle.

The last part of the article talks about a benefit that we all know very well today, which is instant gratification. Digital photographers have the advantage of seeing their results as soon as the image is made, so that corrections can be made with subsequent images. Did you cut off someone’s head or did you miss focus or exposure? Just look at your camera’s LCD to find out and retake if necessary. For the first time ever, film photographers could do the same thing.

In the mid 20th century, such conveniences were science fiction, so for Polaroid to offer results within an instant, the beginning photographer could more quickly get feedback in their images and adjust as necessary. While a majority of people saw the Polaroid camera as an incredible convenience, there were those too that saw it as an excellent teaching tool.

In reviewing this 10 page article, I can’t help but wonder how amazed people must have been when they first read about the Polaroid camera, or seen their first prints. This article is from 1955, nearly seven years after the first Polaroid camera made it’s debut, and in my research for this article, I attempted to find an earlier review of the camera or it’s film, but was unable to. I would have loved to be a fly on the wall and witness the first impressions of both the photographic press and the amateur photographer the first time they saw an instant Polaroid. If I ever do find such an article, you can be sure I’ll be here to write about it!

Although mentioned in the first article, this second from May 1961 goes into greater detail the process of extracting a negative image from Polaroid film. The earlier article mentions the original type 40 series roll film used in the earliest Polaroid cameras. This second one uses Polaroid Type 55 peel apart film, which would have been used in specialized 4×5 backs for sheet film cameras like the Graflex Crown Graphic or Bush Pressman cameras. It would have been a early version of Fuji’s popular FP-110 series of peel apart film.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2021.

I always love Polaroid, starting with my ColorPack II in 1971!!! I truly miss peel-apart film and was a big type 55 user!!!

My paternal grandfather was a successful research chemist and pharmacist, with an early-adopter approach to technology. He had the first color TV, the first portable b&w TV, and the first portable (vacuum-tube) radio in our family. And also a Model 95. Well I do remember using the fixative squeegee thingy on the prints it produced. It was truly a massive camera, especially to a kid under ten years of age – but it was a marvel. I have some original prints from that 95; stored in dark and dry conditions, they seem to last as long as any silver nitrate prints do.

I happen to have one of those monsters along with a 250, 600, and SX-70 all donated to my office. Pretty much useless to me but I have this complete inability to throw them away, like books, unless completely mangled beyond use if there was. So they sit on a shelf, the 95 complete in the box it was bought in with all it’s paper work, in my office because it is a crime for me to even think of tossing them.