This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

Last year, I republished individual versions of each of those reviews in the lead up to the 9th installment of the Cameras of the Dead series in October. This review is from that 9th edition, now finally getting it’s own single article indexable version.

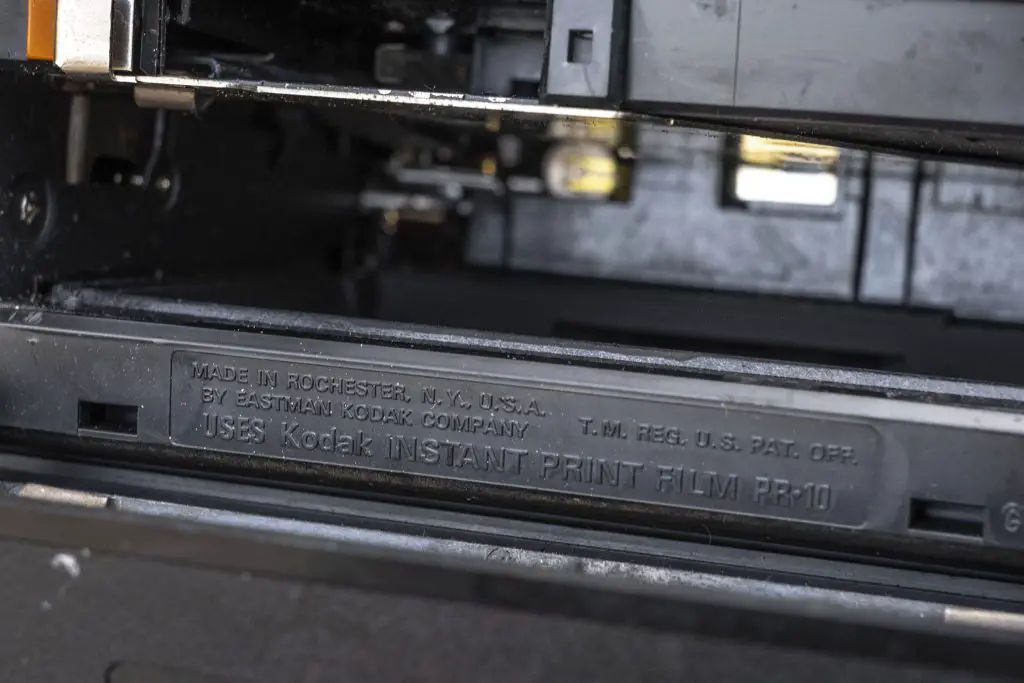

This is a Kodak Colorburst 100, an instant film camera produced by the Eastman Kodak Company between 1978 and 1980. The Colorburst 100 was also sold overseas as the EK100 and was one of the higher end models in Kodak’s new line of instant film cameras, created to compete with Polaroid’s instant film monopoly. Kodak’s instant film system was both simpler and less costly to make and was thought to be a inexpensive alternative to Polaroid’s. The Colorburst 100 had a motorized film transport, full focus capability, exposure control, and a socket up top for an optional flash module. A legal battle would occur in the early 1980s which resulted in 1986 of a federal injunction, prohibiting Kodak from producing their instant film or cameras, abruptly bringing their reign as a Polaroid alternative to an end.

Film Type: Kodak Instant Film Pack (ten exposures per pack)

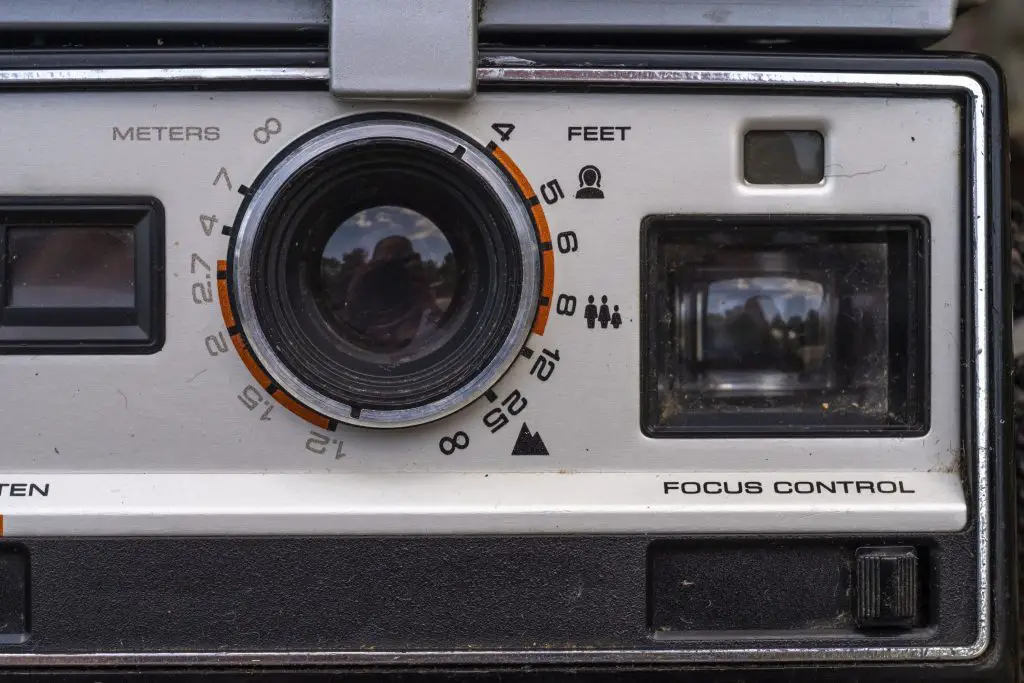

Lens: 137mm f/11 Coated 4-elements

Focus: 4 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with Projected Frame Lines

Shutter: Yes

Speeds: Single Speed, Unknown Speed

Exposure Meter: Coupled CdS Meter with Programmed AE

Battery: 6v Size J / 4LR61 Battery Pack

Flash: Auxiliary Flash Port

Weight: 818 grams, 989 grams (w/ flash)

Manual: https://mikeeckman.com/media/KodakColorburst100Manual.pdf

The Worst Ever?

If you grew up in the 1980s or 90s and someone mentioned instant photography, the name that everyone thought of was Polaroid. Much like Kleenex, Chap-Stick, Xerox, and Band-Aids, each of these brand names became synonymous with their most successful product, even if the product you’re actually using wasn’t made by that company.

When someone needs to blow their nose or make a photocopy of a document, do they actually care if they’re given a facial tissue made by Scott or are using a copy machine made by Ricoh? Polaroid was one of these companies as they were so successful at instant photography that even when there was competition in the market, people still referred to them as Polaroids.

Being the world’s leader in production of photographic film, it’s probably no surprise that the Eastman Kodak Company tried their hand at instant film photography too. With the release of their Kodak Instant film in 1976, Kodak directly competed with Polaroid’s monopoly in the segment.

What many people may not have known however, is that Kodak didn’t just simply decide to start making instant film prior to that film’s release. In fact, Kodak had worked with Polaroid, making the negative part of Polaroid’s instant film from as far back as 1963. In my research for this article, I found the same information over and over that Kodak had planned on releasing their own brand of Polaroid’s roll film to be used in Polaroid cameras but when Polaroid released the SX-70 with it’s new integrated design, they scrapped those plans and started working on something different.

It is unclear how the marriage between Polaroid and Kodak ended. Was it an amicable break up or a bitter one? My best guess is the latter as when Kodak released Kodak Instant in 1976, Polaroid took exception and quickly filed a lawsuit against their former partner, which would eventually lead to the discontinuation of all Kodak Instant film when the lawsuit concluded in 1986.

Despite what sounds like one big company ripping off the technology of another, Kodak’s Instant film was quite a bit different from Polaroid’s. Each exposed image was rectangular instead of square, which was thought to be more familiar to those used to 35mm cameras. Another major change was that Kodak Instant film did not contain a battery like Polaroid’s did. All power came from a battery within the camera, not the film, which allowed the film to be manufactured cheaper, and although it likely wasn’t a big concern back in the 1970s like it would be today, was also better for the environment.

Also, Kodak’s film is exposed directly from the back, rather than reflected via a mirror through the front like Polaroid’s system was. This allowed for more compact and flatter cameras that didn’t need a large angled mirror inside of the camera to reflect the image. Another benefit of exposing from the back is that Kodak’s images could have a matte texture which was more resistant to finger prints, reduced glare, and also allowed for sharper looking images.

Finally, with the later Trimprint feature, each Kodak Instant print could be peeled away from the negative image and development chemical pod after the image was done developing, allowing for just the print to be saved, allowing for thinner, and more easily framed images.

Feature for feature, Kodak’s Instant film was cheaper to make, allowed for less expensive cameras, and also had the benefit of sharper and more convenient prints, so why did it fail? I’m no lawyer, but it seems that despite their best intentions, Kodak got a little loose in their adherence to patent law, violating as many as twelve of Polaroid’s patents. At the conclusion of the lawsuit, Kodak was forbidden from manufacturing any more Instant film and was forced to pay Polaroid nearly a billion dollars in damages.

Like Kodak often did with other film formats, Kodak’s instant film cameras were built as “loss leaders” aimed at the low end of the market, failing to realize the middle to high ends of the market. Unlike Polaroid who produced SLR and professional instant film cameras with rangefinders and high end lenses and shutters, Kodak cameras like The Handle, Pleaser, and the entire Colorburst series were cheaply made plastic cameras with mostly plastic lenses, no faster than f/11 and with the exception of only one model, were all manual focus.

Originally, I was going to say that no other company made a camera that used Kodak Instant film, but then I discovered a model called the Continental Colorshot 2000 which used it, although it did nothing to change the low end perception of Kodak’s instant film.

In January 8, 1986, newscasts like the one below announcing the end of Kodak Instant film caused customers to panic, realizing that they would no longer be able to use their cameras again, calling local photo stores and Kodak themselves asking what they should do.

At the end of this video, it explains Kodak’s proposed three options given to users of their Kodak Instant cameras, the third of which is a single share of Kodak stock. I looked up old issues of New York Stock Exchange stock prices and on January 4th, 1986, four days before the above newscast ran, the price for a single share of Kodak stock was worth 51 1/8 ($51.13).

The fallout over Kodak Instant film was yet another strike against Eastman Kodak in the minds of photographers growing tired of the company’s continued reliance on proprietary new film formats that the company would later abandon. In the early days, formats like 828, 620, and 616 were released, mostly as Kodak specific formats, but later formats like Instamatic “type 126” film and Kodak’s short lived Disc film format both failed to stick around for very long too, adding to a growing pile of Kodak failures.

How to Use It

At the time of it’s release the Kodak Colorburst 100 was the first in the new Colorburst series featuring a full focusing glass lens, exposure compensation, and support for electronic flashes. The next two models in the series, the 200 and 300 added a protective door over the lens and controls plus a battery test button, and a built in electronic flash, respectively.

The Colorburst had a retail price of $44.95 for the camera and $7.50 for a ten exposure pack of film which when adjusted for inflation, compare to $180 and $30 today.

Using the camera was an ergonomic nightmare featuring a large triangular protrusion on the back of the camera that hits you right in the nose as you press your face up to the viewfinder.

On opposite sides of the front top of the camera are two plastic sliders, one for exposure control and the other for focus. The scale focus viewfinder has what Kodak called the “zooming circle” which the manual suggests is only for taking pictures of people. It’s designed in a way where as you change focus on the camera, the size of the circle changes. When the entirety of someone’s head is within the circle, the image is supposedly in focus. Without the ability to shoot this camera, I couldn’t test this myself, but it seems rather crude, and for the life of me, I can’t see how it would work. There is no attempt to aide in focusing when shooting photos of something other than someone’s head.

Take a look at the two images below I took through the camera’s viewfinder. In the left image, the camera is focused to infinity, and in the right, at minimum focus.

Also within the viewfinder is a projected bright line that frames your image and a small red LED that indicates that there is not enough light to properly expose the image without a flash.

With the optional ITT Magicflash seen here, a two position slide is on top that allows you to change flash ranges from 4-6 feet and 6-10 feet. The only difference between the two is that at the closer position, a tinted window slides in front of the flash to lessen it’s output.

The shutter release is in easy reach of the photographer’s right index finger and the only thing seen on the camera’s left side is strangely located 1/4″ tripod socket. The lack of any slow speeds or even the ability to rotate the camera into landscape orientation with it mounted make the inclusion of this socket strange.

The bottom of the camera is hinged to reveal both the battery and film compartment. You better hope you never have to change the Type J lithium battery while film is loaded into the camera as doing so can fog the remaining exposures. Changing film is much like Polaroid’s SX and One Step cameras in which a film pack is first removed from a light protective foil packet, and then inserted into the camera. An orange stripe would have existed along the top of a new film pack to indicate which side of the pack faces up. After closing the camera, you must press the shutter release once to eject the paper dark slide to get it ready for the first exposure.

In my youth, I knew plenty of people who had Polaroid instant cameras, but no one I ever knew had one of the Kodak Instant ones. I didn’t even know Kodak made instant film until after I started collecting cameras, so I can only assume that a large number of people reading this article probably had a similar experience as well.

After reading of Kodak’s improvements to Polaroid’s instant film, I wish I could try one. The thing is, had the lawsuit between Polaroid and Kodak never happened, I still don’t think Kodak would have been much more successful than Polaroid. After holding the Colorburst 100 and looking at the different options that existed, these were cheaply made cameras. There was no higher end model with better lenses and improved build quality.

Kodak was then and always has been, a film first company, and it’s never been more apparent than with these cameras. Kodak made these things for no other reason than to sell film. They had no interest in making a better camera, just something good enough so that people would buy their film and that’s a damn shame, as we’ve seen throughout many different parts of the 20th century, when Kodak really wanted to make a good camera, they did….they just didn’t do it very often.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Kodak_Colorburst_100

https://vintagecameralab.com/kodak-colorburst-100/

https://www.photoandvideography.com/kodak-ek100-the-rise-fall-of-the-instant-camera-158/

https://www.collection-appareils.fr/x/html/camera-141-Kodak_EK100.html

In the late 70s while in College, I worked the the photo department for a retail chain. I remember loving the Colorburst film for its size. It was fun to paly with in the store, we used to have a budget to demo cameras as we sold them!!!

I was a camera store manager at the time and I thought Kodak had hit a home run with their instant print technology. It had better colors than the Polaroid SX-70 and the cameras were built much better than what we expected from the typical Kodak cameras.

The original diffusion transfer color process was a war prize from Agfa after WW II that went to Polaroid. The real problem came from the fact that Kodak was a manufacturer for Polaroid. Polaroid rightly sued because they believed Kodak had stolen formulae and manufacturing secrets. Kodak denied it all and said that they had developed the product without Polaroid technology. Evidence turned up in court showing that Kodak had clearly stolen secrets. Kodak tried to negotiate a patent and damages payment to Polaroid but Polaroid knew they had Kodak in their noose and went for it all. Kodak was found guilty and they had to immediately remedy the situation by removing products from dealers’ shelves, refunding dealers, and offering the customers the options as you mentioned in the article.

Kodak had also introduced a cool 8×10 inch darkroom instant print system which gave reasonably good color prints without all of the dangerous chemicals and equipment. That was pulled out of the market, too. It was expensive but there was nothing else like it at the time. It was a forerunner of later diffusion transfer print systems that you typically found at convention photo booths.

I think Polaroid won the battle but lost the war. They went bankrupt before Kodak did and ended up selling most of their patents to Fuji Film.

Thanks for the awesome response Tom! I love hearing stories like this from people who experienced these cameras first hand, although I am sorry to bring back painful memories!

Hi! I was wondering, is it possible to buy film for this camera nowadays? And where would that be? I may buy a used one and wanted to know if it was worth it if I could keep buying film and using it

Unfortunately no. Film for these hasnt been made since the late 80s. If you want to shoot instant film, get a Polaroid 600 or SX70.