This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

This review is part of the Cameras of the Dead series which I have been publishing every year on Halloween and “Halfway to” Halloween, featuring three cameras that I’ve wanted to review that either didn’t work, or was otherwise unable to shoot.

Last year, I republished individual versions of each of those reviews in the lead up to the 9th installment of the Cameras of the Dead series in October. This review is from that 9th edition, now finally getting it’s own single article indexable version.

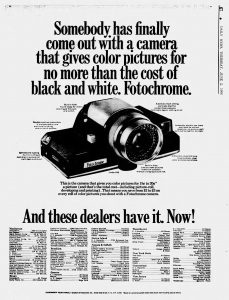

This is the Harrison Fotochrome, a solid bodied medium format camera, manufactured in 1965 by Petri of Japan for the Harrison Fotochrome company of Orlando, Florida. The Fotochrome is a strange looking camera that used a proprietary direct positive color film reportedly made by ANSCO that produced ten 2×3 images per roll. After shooting a roll, the film could not be developed by regular labs and needed to be sent back to Harrison for development. Once you had your pictures, there were no negatives, so no copies or enlargements could later be made without first ordering them from Harrison. The camera itself had an all glass Petri lens and a selenium exposure meter. The camera was point and shoot, with no manual exposure settings of any kind. The only shooting option you had, was whether to use the flash or not.

Film Type: Fotochrome Film Packs, (ten 2 inch x 3 inch exposures per roll)

Lens: Unknown focal length f/4.5, coated unknown elements

Focus: 5 feet to Infinity

Viewfinder: Optical Scale Focus

Shutter: Yes

Speeds: Single Speed, Unknown Speed

Exposure Meter: Coupled Selenium Cell

Battery: 2x AA Alkaline for Flash Only

Flash Mount: Built in Flash Reflector for M3 Flashbulbs

Weight: 740 grams

Manual: https://www.cameramanuals.org/pdf_files/fotochrome_color.pdf

The Worst Ever?

It’s easy to look at a camera like the Traid Fotron and point out all of it’s failures, but at the very least, it did have a specific target customer and although they were poorly executed, some of the camera’s features like the in body electronic flash and the ability to recharge it were pretty cool.

One camera that I can’t think of a single good thing to say about, is the Harrison Fotochrome, an ill-conceived and goofy looking medium format camera produced by a Florida based photofinishing company using proprietary film that can only be developed by sending it back to Harrison, the Fotochrome was such a spectacular failure at every step of the way, that unused cameras, still in their original packaging can easily be found today.

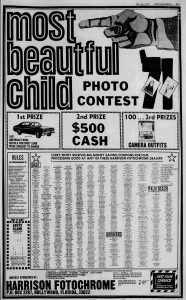

Not much exists online about the Harrison Fotochrome company, but as best as I could tell, they ran a network of photo finishing dealers from the early 1960s to the early 1970s, mostly in pharmacies and department stores, but possibly had some retail stores as well. The ad to the right announcing a “Most Beautiful Child” contest has a list of over a hundred Harrison Fotochrome dealers in the Florida area. Public records on a Florida Commerce website suggest that the company was founded on April 1st (no joke), 1961.

At some point in the early 1960s, someone at the company thought it wasn’t enough to simply develop film made by Kodak and other companies, they thought that perhaps they could expand their reach by coming up with their own camera that used a unique type of film that only they could develop.

Harrison would come up with the design of their eponymous camera, but it would be built in Japan by Petri. The camera would use a proprietary direct positive film made by ANSCO with an ASA rating of 10. The film had an opaque plastic backing, so it could only be exposed through the front, similar to Polaroid’s SX-70 instant film, via a large mirror that reflected the lens image onto it as the shutter opened.

Each roll of film was good for ten 2 inch by 3 inch exposures. It was loaded through the bottom of the camera in a spool to spool fashion and then transported through the camera manually after each exposure was made.

The lens was said to be a Petri f/4.5 lens of unknown focal length and construction. Considering this camera was meant to be inexpensive, and 2×3 prints would are marginally smaller than 6cm x 9cm prints, my best guess is it’s a ~85mm triplet.

Exposure control was completely automatic, via a coupled selenium meter around the lens that controlled the aperture based on available light. I never found any info about the camera’s shutter, but my guess is it’s a single speed design, probably fixed at something like 1/25 or 1/30 of a second to make the most out of the slow ASA 10 film speed.

The ad to the right suggests a price for the camera of under $50, and a per exposure cost including developing of between 15 to 20 cents. Assuming a $2 roll of film (20 cents times 10 exposures) and a $50 camera, when adjusted for inflation, those prices compare to $410 and $16.50 today.

The Fotochrome was designed to be easy to use, so there’s very little in the way of controls for it. Looking down upon the top of the camera, a curved metal reflector for the flash dominates the center. Pressing a small white button to the right pops it open. Forward of the flash release button is the larger, white rectangular shutter release button.

The Fotochrome has double image prevention, so you cannot press the shutter release until after advancing the film, which is done by the large metal wheel on the back of the camera.

The exposure counter is subtractive, showing how many of the ten exposures remain on a roll of film. To the left of the exposure counter is a thin knurled wheel which is how you reset the exposure counter back to ten after loading in a new roll of film. On the far left side of the back is the opening for the viewfinder. Finally, in the center of the back, immediately behind the flash “hump” is the battery compartment where two AA batteries are installed. Having never used this camera, I believe the batteries are only needed for the flash, and not the shutter itself as I think it’s all mechanical.

The bottom of the camera is a large metal film compartment door with 4 small feet to protect it when setting on a flat surface. Opening the door requires sliding a latch on the side of the camera nearest the film advance knob. The door is hinged on the side opposite of the release latch. The first thing you’re likely to see when looking into the film compartment is the large angled mirror that reflects light from the lens to the film plane. The mirror looks like that from a reflex camera, but instead of directing light into the viewfinder, it directs it towards the front of the unexposed film. At a quick glance the film compartment looks like that from a normal 120 roll film camera. Upon closer look, each chamber is larger to accommodate the plastic cassettes that each spool comes in.

Reading the camera’s user manual, it appears that new Fotochrome film came with both a supply and take up cassette already connected by the film’s backing paper. Installing the film looked to be very easy. Simply separate the two cassettes about 2 inches and then press the both into their respective chambers and close the door. At the end of the roll of film, you wind the film into the take up cassette and then send it in for developing.

The viewfinder is just a straight through window, showing an approximation of the exposed image. There are no frame lines or any types of focus aides to estimate focusing distances. To the right of the viewfinder is a small circle that should normally be clear when there is sufficient light for an exposure, with a red flag that will appear where light is too low. Amazingly, the meter still seems to work on this example as I saw the red flag move in and out depending on how much light was hitting the selenium cell.

The only other control on the camera is the focus knob around the lens which supports distances from 5 feet to infinity (indicated by an icon of mountains). Although there was no wobble in the focus ring, it feels cheaply made with no dampening, like as if it’s just a metal ring wrapped around the metal lens tube.

The cheapness of the focus ring is prevalent throughout the entire camera. Despite weighing what seems to be a sturdy 740 grams, the entire camera feels lightweight and cheap. The body is mostly some type of die cast plastic, with most metal surfaces being stamped metal. The focus knob has a nice feel to it but otherwise there is nothing luxurious about the camera. With a retail price of under $50, the build quality seems on par for the price, so had the camera used a non-proprietary film, there’s a chance this thing might have been more successful.

Of course, we know now that the Fotochrome wasn’t successful. In a December 2007 post on photo.net, a user named Adolphious St. Clair who claimed to be an employee of Harrison Fotochrome when this camera was sold, says that within 6 weeks of the camera’s introduction, returns of the camera started pouring in as a great deal of them didn’t work properly. Problems with film advance, the flash, and even shutter parts being installed upside down were common problems suggesting an almost non-existent level of quality control.

Word must have quickly spread of the Fotochrome’s reputation as it was only in production for a short time. A huge number of models were never sold and some still remain in their original packaging to this very day. The example I used for this review is one such camera that I picked up on a whim for around $20 in unopened condition.

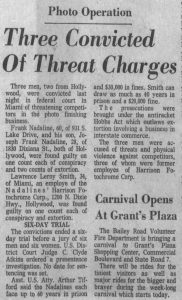

It would seem that Harrison Fotochrome’s business was not affected by the failure of the Fotochrome camera, at least not at first. In my research for this article, I found many advertisements for Harrison’s photo finishing services through the early 1970s, but then in 1971, the company would find itself in the midst of an extortion and racketeering scandal involving company chairman and business operations manager Frank Nadaline and his son, Joseph, who with another employee were charged and later found guilty of trying threatening the life of former Harrison Fotochrome employees who had gone on to work for a competitor.

It would seem that Harrison Fotochrome’s business was not affected by the failure of the Fotochrome camera, at least not at first. In my research for this article, I found many advertisements for Harrison’s photo finishing services through the early 1970s, but then in 1971, the company would find itself in the midst of an extortion and racketeering scandal involving company chairman and business operations manager Frank Nadaline and his son, Joseph, who with another employee were charged and later found guilty of trying threatening the life of former Harrison Fotochrome employees who had gone on to work for a competitor.

During the trial, it was revealed that multiple ex employees were threatened with bricks thrown through windows and in one case, a vehicle was set fire with various other threats made.

In each of these two news clippings, both from Florida newspapers in 1971, the fate of the company was never mentioned, but it can be assumed that after such a scandal, things did not continue to go well for the Harrison Fotochrome company. In a legal notice that appeared in the November 13, 1980 edition of the Miami Herald, it was revealed that the company had filed for bankruptcy protection on February 2, 1976 in the Broward County, Florida circuit court, confirming the company did not survive the 1970s.

Shooting the Fotochrome

Unlike the Fotron, the Fotochrome is the only that appears to work correctly. The film advance works as it should, the shutter fires, and even the exposure meter detects light. The requirement of proprietary film however, is the deal breaker making this camera impossible to shoot without modding it to use 120 roll film.

When I first acquired this camera back in 2018, I had thought of attempting to shoot the camera using one of the mods online, but here we are more than two years later and that hasn’t happened. There’s two articles online, one on Instructables, and another by Stephen Connolly on his blog. Both methods require a little more than the typical extinct film mod due to the way the camera works and even after successfully getting regular 120 film to transport in the camera, you still have to deal with the Fotochrome’s slow shutter which was designed for the original film’s ASA 10 speed rating. The simplest way to do this is to simply tape some type of neutral density filter over the lens to reduce the amount of light entering the camera. It’s a rather convoluted process for a cheaply built that camera that frankly, in two years, I could never build up enough excitement to want to try.

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Fotochrome

https://www.instructables.com/Mama-Dont-Take-My-Fotochrome-Awayyyy/

https://www.refracted.net/fotochrome.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/the-amazing-fotochrome-camera.223545/