This is a Zeiss-Ikon Cocarette 519/2, a folding bed camera that shoots 6cm x 9cm images on 120 roll film. The Cocarette was considered a premium model in Zeiss-Ikon’s post merger catalog. Originally a Contessa-Nettel model that was first produced around 1919, the Cocarette was continued under the Zeiss-Ikon brand until around 1930. Featuring a unique self-contained film compartment that pulled out separately from the rest of the body, the Cocarette series had a lightweight one-piece aluminum body covered with fine saffron brown leather and often came with premium lenses and shutters. These were generally regarded as some of the finest roll film cameras money could buy at the time.

Film Type: 120 Roll Film (eight 6cm x 9cm exposures per roll)

Lens: 10.5 cm f/4.5 “Dominar-Anastigmat” uncoated 4-elements

Focus: 1.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Scale Focus with 35mm Projected Frame Lines or Coincident Image Coupled Rangefinder or Fixed SLR Pentaprism or Coupled Reflex Viewfinder

Shutter: Klio Leaf

Speeds: T, B, 1 – 1/100 seconds

Exposure Meter: None

Battery: None

Flash Mount: None

Weight: 603 grams

Manual: None

How these ratings work |

The Zeiss-Ikon Cocarette was a high end folding bed camera with a unique removable film compartment. These models usually came with higher end lenses and shutters, and can often still be found in working condition. Although they came in a variety of sizes, this model shoots 120 roll film which is still easily found today. The shooting experience isn’t much different from other cameras of it’s type, which is to say pretty easy, and a lot of fun. If you’re looking for a nearly century old folding camera to try out, you could do a lot worse than a Cocarette. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 40% | |

| Bonus | +1 for a unique pull out film compartment | ||||||

| Final Score | 12.2 | ||||||

History

August Nagel was one of the most recognized and successful camera designers of the 20th century, but his name is most commonly associated with his time working for Eastman Kodak, or for his short lived eponymous company, Nagel Kamerawerke from 1928 to 1931 where he came up with many of the designs that would continue to be sold while working for Kodak.

If you only think of Nagel for the Retina or other Kodak cameras, you’re missing a big part of his history as he had a long history of making cameras before George Eastman ever approached him.

August Nagel was born in June 5, 1882 in Stuttgart, Germany. (There is at least one article online which suggests Nagel was born in 1867, which I do not believe to be true.) In his younger years, he worked in various small machine factories learning business and the inner workings of mechanical objects. Despite being a skilled mechanic, Nagel’s passion was photography, and he would devote his free time to the design and construction of primitive cameras.

In 1908, at the age of 26, he founded his first company with childhood friend Carl Drexel, called Drexel & Nagel of Stuttgart. Drexel & Nagel’s first camera was a very compact camera called the Contessa No.1 which made 4.5cm x 7cm images on what I can only assume was some type of early roll film. In my research for this article, I was not able to find any images or any other information about what this first Contessa would have looked like.

Drexel & Nagel saw almost immediate success, and in 1909, renamed itself to Contessa Camerawerke Stuttgart, and by 1910 had developed as many as 23 different models, many of which were exported all over the world.

By the start of World War I, Contessa Camerawerke employed over 500 people, and during the war, would switch production to making armaments for the German war effort. After the war had ended, the German economy was in disarray and many German companies were unable to stay in business. One of these companies was Nettel Camerawerk from Sontheim am Neckar, Germany. Nettel had been in business since the early 1900s as a maker of folding medium and large format cameras.

In 1919, Contessa Camerawerke would take over the floundering Nettel Camerawerk and become Contessa-Nettel AG. An early Contessa-Nettel model was called the Cocarette which was a folding bed roll film camera that had a unique film loading design in which the film compartment would slide out of the bottom of the camera as it’s own separate piece. A new roll of film would be installed onto the spools and the entire film compartment would be slid back into the body of the camera. This guaranteed a near light proof film compartment and also had the advantage of a perfectly flat film plane, guaranteeing consistently focused images.

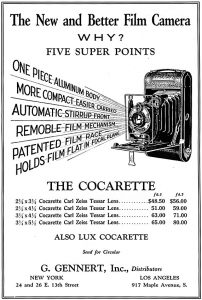

The Cocarette was sold both in Germany and exported to the United States, sold by a variety of importers as a premium German built folding camera. The ad to the right from a 1926 advertisement for G. Gennert in New York shows the Cocarette in four different sizes from 2 1⁄4 × 3 1⁄4 (120 roll film) to 3 1⁄4 × 5 1⁄2 (122 roll film), all with a Zeiss Tessar lenses for $48.50 to $80, which when adjusted for inflation, compares to $720 to $1190 today making the Cocarette quite a luxury item at the time.

Although Contessa-Nettel had success in the 1920s, the entire German economy continued to suffer after World War I, causing a lot of instability in German industry. While the largest German companies were able to continue operations on their own, there was a growing number of smaller German companies that were struggling to stay in business. Contessa-Nettel AG was not immune to the struggles of the economy, and as a result in 1926 would partner with several other German camera makers like Erneman, Goerz, ICA, and Zeiss to form Zeiss Ikon AG.

While the idea of combining forces of several smaller companies into one larger company was probably a good way to stay in business, August Nagel found himself for the first time in his career to not be in charge of his own company. Prior to his partnership with Zeiss, he had free reign to design and release new models to his heart’s content, but now, he had to answer to a board of directors, all made up of executives from these other companies who didn’t always see eye to eye with Nagel’s vision. This would leave to the eventual departure of Nagel from Zeiss-Ikon, but that’s a story for another article.

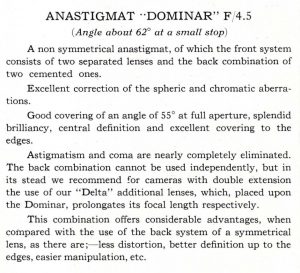

The Dominar Anastigmat was a step up from the f/6.8 Novar and Hekla Anastigmats, but below the f/4.5 Zeiss Tessar. The description to the right comes from an Ica catalog, explaining the virtues of the Dominar lens.

In my research for this article, I found some catalog references to a Cocarette Junior, which had the same unique film compartment and all metal body, but had fixed focus f/6.3 Novar lenses, and black painted trim.

Oddly, in all of the Zeiss-Ikon catalogs I searched from 1927 to 1932, I could not find a Cocarette exactly like the one I have with a f/4.5 “Dominar-Anastigmat” lens and Klio shutter. The Dominar name was commonly used by Contessa-Nettel prior to the 1926 merger, but the presence of Zeiss-Ikon plainly engraved on the Klio shutter (which itself is a Zeiss brand) suggests a post merger model.

Today, Cocarette cameras are extremely collectable, especially the higher end “Luxus” models. A combination of prewar German “nickel and leather” design that is appealing to most collectors, plus a unique and uncommon design, often cause these cameras to ascend to the top of most collector’s wish lists.

Finding an example in good condition for a reasonable price can sometimes be difficult as cheaper examples are often quickly snatched up, but if you’re patient, a model like this Dominar equipped example might cross your path.

My Thoughts

There isn’t a ton of variety in early folding bed cameras. Sure, they came in a variety of sizes, shooting films like 127, 120, 116, 122, 130 and a few others, and there were an almost unlimited number of shutter and lens combinations, but in terms of their operation, most of them are the same.

The Cocarette is an exception to that rule in that the entire film compartment separates entirely from the main body of the camera. These were premium cameras both when sold by their original company, Contessa-Nettel, and also when they were continued by Zeiss-Ikon. They all had a single piece aluminum body, covered with premium leather, and came with mid to high end shutters and lenses.

Separating the camera from it’s film compartment requires sliding the lock on the camera’s right side and pulling that entire side of the camera out. On my example, this required an uncomfortably amount of effort, something likely made worse by nearly 100 years of age. While I doubt this was ever an easy process, my guess is even when these cameras were new, there was still a bit of effort required.

With the film compartment out, we see the 6×9 metal film gate and chambers for both the take up and supply spools. Both sides have a spring loaded arm that holds the spool in place, allowing you to reinsert the loaded frame back into the camera without having to worry about the spools flopping around. The take up spool goes on the same side as the winding key, which in the image to the right, is on the left.

When loading in a new roll of film, you must pass the paper leader beneath two metal channels on the long side of the film gate. Failure to do this not only will not only make inserting it back into the camera difficult, but it would likely damage the film as well. See the image to the left with the backing paper correctly traveling beneath these channels.

As you would while loading any roll film camera, attach the paper leader to the take up spool and wind it enough times so that the film is securely attached, and then insert the entire frame back in the camera, taking care to feed the paper backing through the narrow slit on the back of the camera body. Once everything is back together, remember to lock the camera again.

With a fresh roll of film in the camera, you must use the red window on the back of the camera to advance it to each of the 8 exposures you’ll get. As with all cameras of this era, you must take extra caution not to allow excess light to hit that red window as modern films are much more sensitive to red light, and direct hit from sunlight, even for a second, could cause unwanted exposure through the film’s backing paper. This is especially true if you use a faster film. In my case, the red window was still in good shape, but while shooting I hung a piece of a red gel filter over the window to protect it.

You’ll also notice a large circle on the back of the camera which contains the back post for the wireframe sports finder, but doubles as an inspection window for the inside of the camera. If you need to check shutter speeds or clean the rear lens element, give this circle a twist using the two metal posts and it will come off. As a 21st century alternative, some crafty camera hackers have found ways to use this hole to adapt the Cocarette to a digital camera, using the entire camera as a lens.

With the camera closed, the Cocarette is quite compact, at least compared to other larger folding cameras that used 116, 122, and 130 roll film formats. To open it up, press a small release button on the side of the camera, next to the film advance key. The front door will pop open a small amount, but requires you to help it open the rest of the way. Extending the lens and bellows requires you to grip two posts opposite of the Zeiss-Ikon logo beneath the shutter and pull until the bellows are fully extended.

As with most folding bed cameras from this era, there is no obvious “top” to the camera as nearly every meaningful control is on the front. From this angle you see the brilliant reflex finder in it’s portrait orientation. You can swivel it 90 degrees to the side for landscapes, which is the more likely way to shoot the camera, but it’s important to remember to swivel it back upright before trying to close the camera up again.

As an alternative to the reflex finder, a hinged wire frame finder can also be used for fast action shots. To use it, swing out the finder so that it sticks out to the side of the camera and lift the peep hole finder on the back of the camera as far as it will go. Position your eye as close as possible behind the peep hole so that you can see the entire wire frame through the peep hole. Anything you see within the wire frame is what will be captured by the lens. Many folding cameras of this era have these sort of wire frame finders, but I find them impossible to use with prescription glasses.

Up front, the Klio shutter is what’s called a dial set design with a dial at the 12 o’clock position for changing the shutter speeds from 1 to 1/100 seconds, plus T and B modes. This shutter is self-cocking, which means that a single motion of the shutter release both cocks and releases the shutter. This is both good and bad, in that it simplifies making an exposure, but it also increases the chances of an accidental exposure. In the image to the left, you can see a small shutter release cable is threaded into the shutter, and folded up around the back of it. Although any kind of modern shutter release cable can be used on this camera, these old braided cloth designs are fragile and is only here for decoration. If I actually wanted to use it, I would remove this one and attach a different one. Finally, f/stops from f/4.5 to f/32 are selected using the sliding lever near the bottom of the shutter.

Focusing the camera is done using the curved slider on the bed of the camera. An ivory colored plate has distance markings from 1.5 meters to infinity. With the lever at infinity, there is a lock that must be overcome by pressing down on the slider while moving it.

As was the case with any product with the Zeiss-Ikon name on it, the Cocarette is a quality build instrument. This particular example might have been a lower end variant, but the build quality is stunning. The leather covered aluminum body is well constructed and rigid, without any flex of any hint of cost cutting. The camera’s various controls are all nicely appointed and functional. The shutter still worked at all speeds, down to 1 second without any need for flushing or any kind of service. The leather bellows are still in good condition and passed the flashlight test without any noticeable light leaks.

The Cocarette wasn’t an inexpensive camera when it was new, and although this camera’s original owner could have never known that nearly 100 years later, some guy on something called the Internet would be writing about it, this particular example has stood the test of time extremely well as I suspect many other Cocarettes have as well.

My Results

With a top shutter speed of 1/100 and the only one that appeared to consistently fire at the same speed, I chose a film that would pair well with that speed, without being too slow, and for that, I picked my first ever roll of CatLABS X Film 80, a new black and white fine grain film that claims to “follow in the footsteps” of Kodak’s Panatomic-X, a claim that I was very much interested in checking out. Despite the film speed rating of 80, the manufacturer plainly states that rating this film as a 100 speed film is fine, so it seemed to be a perfect match for the Cocarette’s first roll, in probably more than half a century.

Cocarettes came with a variety of lens and shutter combinations and as best as I can tell, the Dominar-Anastigmat and Klio shutter on this model makes it one of the lower end models, yet, looking at these pictures, there’s a level of vintage awesomeness that I am not sure a better lens would have captured.

My selection of CatLABS 80 seemed to have been a great choice, even though I under exposed a few of the shots. Center sharpness and overall contrast are both very good, but what really makes these images stand out is the rendering that could only be captured by a nearly 100 year old uncoated double anastigmat lens. I am not sure I agree with their claim that the film is comparable to Panatomic-X, but that’s a discussion for a different article.

The lens on this camera is in excellent condition with no noticeable haze or fungus in it, yet the images all exhibit a “glow” and soft vignetting around the edges that likely wouldn’t have been there with a better lens. The Klio shutter seems to be accurate as my hand held shots in the canyons at Turkey Run State park only show the slightest hint of motion blur. In hindsight, a tripod would have been a good idea while shooting on those trails, but the fact that I was able to get these all hand held is impressive.

As is the case of all folding bed cameras like this, framing the image was a little tricky as I was off by a bit on some of them. It’s most obvious in the shot of the front of the Wilkins Mill Covered Bridge where I didn’t get it quite centered. The reflex viewfinder was pretty cloudy and had lost some of it’s silver reflecting layer, making it hard to use. As a wearer of prescription glasses, getting my eye close enough to the rear peep hole to be able to use the wire frame finder was also a challenge, so for most of these images, I just guesstimated my composition, and clearly I didn’t nail it.

My inexperience aside, shooting the Cocarette was pretty easy as there’s not much to go wrong. Even though this was sold as a premium model, it was still designed for novices to use. Remember that at the time, professional photographers still largely used studio cameras, or medium format SLRs like those made by Graflex.

By far, the biggest challenge of using a folding bed camera today is in it’s fragility. I chose to take it hiking at a state park, which in hindsight probably isn’t the best place to shoot a nearly 100 year old bellows camera as I needed to keep folding it shut and inserting it back into the protective casing inside of my camera bag. A single drop or a finger into the fragile bellows is all that it would have took to permanently render the camera inoperable. If I were to give advice to someone new to shooting a camera like this, it would be to mount it to a tripod and leave it open while you move the entire assembly from shot to shot to minimize the chances of some kind of damage.

I really liked shooting the Cocarette and love the images I got from it even more, but despite all the good things I have to say about it, it’s probably not a camera I’ll come back to often. Using it requires a greater level of concentration and care, and even though the images I got from it were very distinct looking, I can recreate the look with many other, more rugged or dependable cameras in my collection. Nevertheless, I am absolutely happy that I took the time to shoot this camera and would recommend it to anyone else, if given the opportunity!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/Cocarette

http://photo-analogue.blogspot.com/2016/11/zeiss-ikon-cocarette-51915.html

https://www.photo.net/discuss/threads/contessa-nettel-cocarette.262500/

https://connealy.blogspot.com/2012/08/contessa-nettel-cocarette.html

https://mikeeckman.com/photovintage/vintagecameras/cocarette/index.html

I once had an Ernemann Heag model 16, made about 1914. It offered a fully removable rollfilm back that interchanged with a cut film holder with ground glass. The rollfilm back had a dark slide. Both backs held the film in the exact same plane of focus. Those guys in Dresden were pretty darn creative!

Great review. I have been shooting a pretty good number of German folders over the last few years. One thing I have noticed is that the leather bellows used by Zeiss are, generally, very resilient; much more so than Kodak bellows or others.

I have what looks to be a Zeiss Ikon Cocarette with Zeiss Ikon (Z D M) shutter and a f/4.5 Dominar 10.5c lens – remarkably the shutter seems to function perfectly – speeds untested. I believe this is a 120 film model based on lens type/focal lenght and web research. Questions I have, since I’m not sure I will be able to see the paper backing numbers through the red window – is there a guideline for how much to advance the the winder between each of the 8 frames? My camera doesn’t have the small button next to the film advance winder. Also, how do I know if the bellows are fully extended? Is it just that it stops? Mine goes out maybe 1mm beyond the rails – but I don’t know if there is a mechanical stop. Do you recommend a method for achieving focus – the viewfinder is nice but very tiny – maybe use a loupe over it – or do you just guestimate with the meters-inifinity focus? Infinity focus would have to be accurate, thus my question about knowing if the bellows is at full extension. My camera has a post (mounted on the back metal lens board the shutter is on) with a small hole in it that looks to maybe have had a wire going through – up to near the shutter speed dial – maybe this was somehow used to indicate a fully extended bellows? My sample doesn’t close completely there may be an issue with the silver pull tab – the rails seem to hit the shutter speed dial (among possible other parts) when trying close completely. It smells really old timey and wonderfully leathery.

I was able to answer some of these questions by reading your article more carefully! The posts on my shutter board are probably for a hinged wire finder. I realize now the Brilliant finder is only for composing. I put some paper with markings through the back to test the red window, and it looks like I will be able to see through it. I’m hoping my film’s backing paper will be appropriately marked for 6×9 shots. I did notice a small seam of light coming through a point on the circle back cover near the sports finder when I was inspecting the insides. I’m hoping this will not be an issue due to the way the film paper will cover this area. I see my camera does indeed have a single stop on the rail floor that stops the bellows from extending, I will assume this is infinity focus. I wasn’t able to verify this by looking through the lens with the back cover removed. I will have to do some experimenting. Did you just shoot at infinity, did you use the meter focus? Did you find one to be better? I do still wonder if the 1mm or so that my bellows extends beyond the rail and hitting the infinity stop is infinity or if it will make a difference. I’m still not 100% sure why mine doesn’t close completely. I think the silver pull tab on the front may be bent in an odd way or the bellows isn’t getting compressed completely. I’m going to try some HP5+ first but am also interested in Panatomic-X. I had the pleasure to shoot a few expired 120 rolls of it in the past as well as Polaroid Type 55) – the Cat Labs film you mentioned is also out of production, so I may also try some Pan F. Thanks!

HI, I Have a Cocarette with Contessa-Nettel written on the lens. I didn’t see any other markings as to determine a model. The camera is in amazing shape except that the shutter doesn’t function. Is there a site that you know of, or you may know, how to disassemble the lens assembly to repair the shutter component? BTW, Most excellent article! Thanks!!!

Kevin, search YouTube for a repair video of any small folder with the same shutter. There are many well-produced repair videos out there … I’ve improved my repair skills by watching them.

Thanks Roger, I’ll check it out

Update: I managed to get the front lens assembly off using some large pliers (it was on super tight) after the lens was removed, I used a micron needle to push back on the shutter fin about .05mm and the shutter snapped fully open. I then continued to exercise the shutter assembly and it started working fine even at various shutter speeds. Guess it was hung up from not being used for years. In any event, I now have a fully functioning camera ! Can’t wait to take some pictures.

Update: I managed to get the front lens assembly off using some large pliers (it was on super tight) after the lens was removed, I used a micron needle to push back on the shutter fin about .05mm and the shutter snapped fully open. I then continued to exercise the shutter assembly and it started working fine even at various shutter speeds. Guess it was hung up from not being used for years. In any event, I now have a fully functioning camera ! Can’t wait to take some pictures.