When Edwin Land released his first Polaroid Land Camera Model 95 in 1948, the world forever changed with the possibility of instant photography without the need to wait for a lab to process your film. Now with a Polaroid Land Camera, you could see the results of your image in as little as a minute or two later.

If you grew up in the 1980s like I did, your exposure to Polaroid film was that of the type 600 and SX-70 integrated film that came on single sheets with a white border. Back then, most Polaroid film was color (at least the ones my family had). But this wasn’t always so.

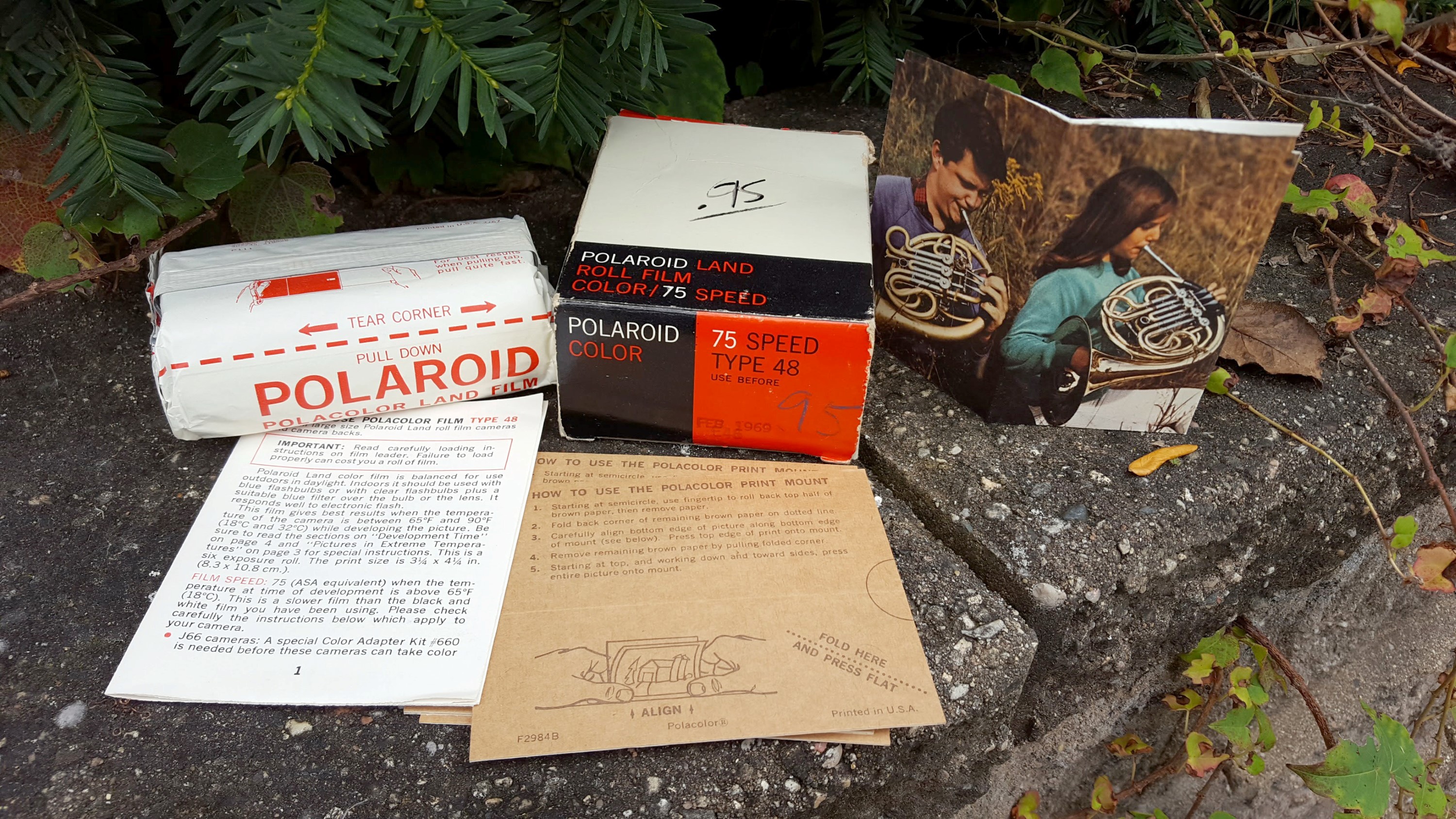

For the first decade and a half of Polaroid’s existence, instant photos were black and white and came in a roll film format in which the photographic negative and development chemicals came on separate rolls and were pressed together with metal rollers to begin the development process. The most common types of Polaroid film were in the Type 40 and 30 series of films. Type 40 film was larger and what was used in the original Model 95. Each roll produced eight 72mm x 95mm prints. Type 30 was introduced in 1954 and made eight 54mm x 72mm prints per roll.

Throughout both the 40 and 30-series, the film continually evolved, improving the quality and speed of the film, while maintaining backwards compatibility with the cameras that used it.

That all changed in 1963 when Polaroid announced that they had developed their first instant color film. The new film was marketed under the same Polacolor name that Polaroid had previously used for a type of 35mm cinema film that used a three color dye to compete with Technicolor.

This week’s Keppler’s Vault brings you an article from the March 1963 issue of Modern Photography where author John Wolbarst both covers the practical and highly technical nature of the film. After reading the article in which Wolbarst explains how Polacolor film uses 8 separate layers of various chemicals to make the whole thing work, I’m more confused about it than before I started. While fascinating, I’ll just tell you this stuff was straight up black magic.

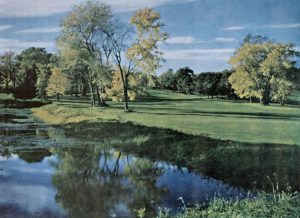

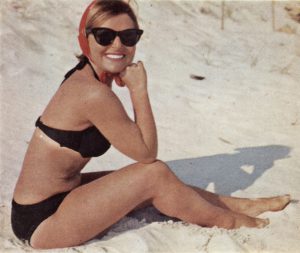

Despite reviewing what was pre-production film, Polacolor film had wonderful skin tones that compared favorably to Kodacolor. Greens and blues were good too, but reds were the film’s weakness. Improvements to accurate reds were something that Polaroid was aware of and improving up to and after the film’s debut. Shadow detail was said to be excellent and resisted turning blue like other color films of the day. Sharpness and detail was very high, suggesting that prints could be blown up to much larger sizes while retaining a good amount of detail.

The film had a variable speed that changed with temperature. A practical measurement of the film speed was that it roughly matched the outside temperature in degrees Fahrenheit. At room temperature, the film behaved like a 70-75 speed film. In the cold it slowed down to 50, and in hot temps it sped up to around 100. I am unsure if later Polaroid film behaved this same way, but if it did, that would explain the frequent warnings to keep Polaroid film away from excessive heat and cold.

At speeds approaching ASA 100, Polacolor was considered pretty fast for a color negative film, as Kodak’s original Kodacolor from the 1950s was rated at 25, and later Kodacolor-X was rated at 64. Kodak would not have a 100 speed color negative film until 1972 with Kodacolor-II.

Another advancement of Polacolor compared to Polaroid’s earlier films, is that the film did not require a separate coating process to protect the film after it was developed. With both 40 and 30 series black and white film, each time you’d buy a new roll, you would get a roller with a special film coating that you had to roll over the developed print to preserve it. With Polacolor, a hardened layer would develop automatically within a few minutes after the exposure appeared.

John Wolbarst was clearly impressed with Polaroid’s first attempt at an instant color film, suggesting that the film should continually improve with even more accurate colors and faster development times. He predicted some of Polacolor’s advancements, such as the self-sealing protective layer would soon appear in Polaroid’s black and white films, and that 4×5 sheet film versions of Polacolor would soon be available.

He was right on all counts as Polacolor continued to get better, eventually leading way to Polaroid’s integrated films with the release of the SX-70 in 1972. Although Edwin Land’s original Polaroid company would go out of business and discontinue all of it’s film formats in the early 21st century, instant film photography lives on today with the unrelated Polaroid Originals line, plus FujiFilm’s Instax lineup of instant cameras.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.