Having revealed a little of what it looks like behind the curtains in my recent post, So You Want Your Own Photography Blog, I talk about the challenges in setting up a website that can be used for any photographic discussion, from reviews of new or old equipment, sharing photographic accomplishments, and pretty much anything you want.

In today’s “digital” era, a large amount of information consumed by photo enthusiasts comes from sites like mine, many of which have questionable technical testing processes. Since anyone can set up their photography blog, the quality of information about cameras and lenses can vary wildly, which is why I try to stick more towards the historical side and “use of” discussions.

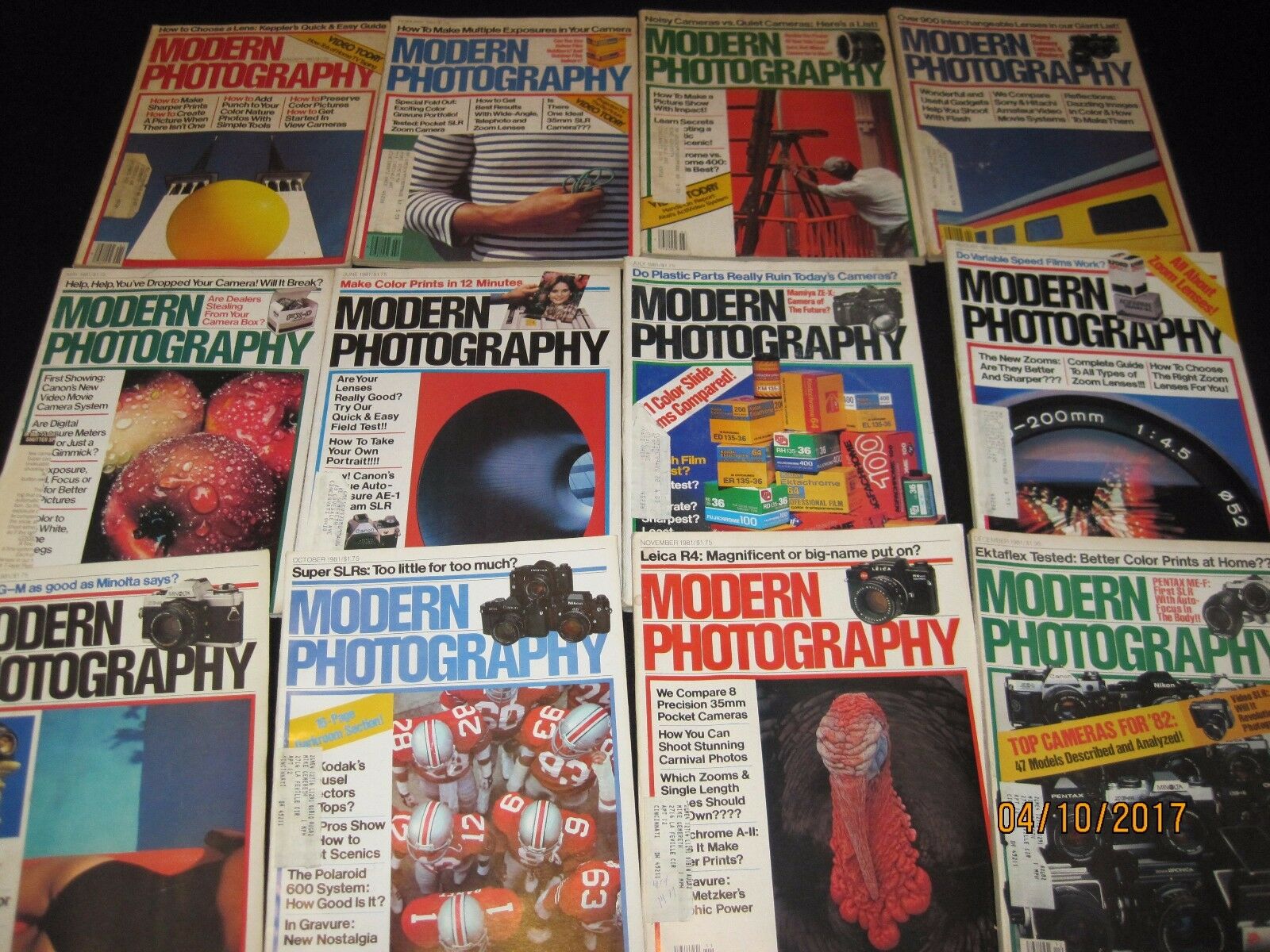

Things didn’t always use to be this way however. There was once a time when people like me and you waited for their monthly delivery of magazine subscriptions of publications like Modern Photography and Popular Photography. These were heavily funded magazines run by some of the most respected individuals in the photography world.

Their desire to accurately measure the sharpness of a lens or the performance of the latest electronic shutter meant that when you read a review of a new camera, it had been subjected to countless hours of lab and field testing. People like myself who would read these magazines often took for granted how much time and effort was put into testing a new camera or lens, so for this week’s Keppler’s Vault, we look at the June 1984 issue of Modern Photography who pulls back the curtains on Modern’s extensive testing facility.

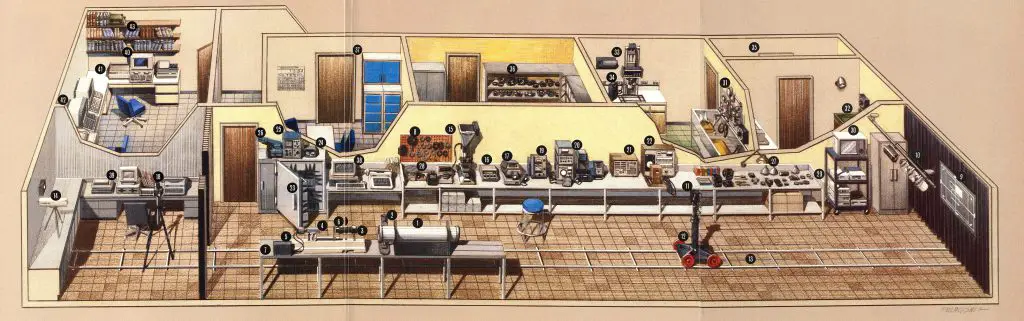

The article starts off with some impressive statistics, saying that they’ve tested 473 cameras and 768 lenses in their elaborate 2320 square foot testing facility. When choosing the facility, the location of the building and floor which the lab would be placed was measured with something called a vibrometer to measure the amount of vibrations in whatever building they were considering, trying to eliminate any testing errors caused due to the vibrations common in New York City high rises.

Upon entering Modern’s secret facility, you’d be blinded by the bright lights and whirring computers and various testing machines. Inventory was logged in something called a Hewlett-Packard 1000 computer, which today is probably about as advanced as the clock on my microwave oven, but in 1984 was state of the art.

Cameras are inspected and disassembled to see how well they were constructed, lenses are checked for proper focus collimation, and put through rigorous sharpness and performance tests, and shutters are fired constantly to see how their speeds hold up.

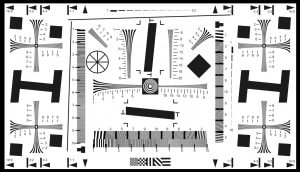

I read the section on lens sharpness a couple of times and my head spun as I was both amazed at the amount of effort that went into these tests, but also at my inability to fully understand what they were trying to do.

This is especially impressive considering film resolves far less detail than modern digital sensors, so whether you had a lens with average or a high level of sharpness back in 1984 when this article was written, most photographers would never know the difference with 4×6, 5×7, or even 8×10 prints. Today, all you need to do is open your digital RAW images on your 4K LCD display and zoom in to see the sharpness of your lenses.

The article gets pretty technical in nature, but it’s impressive to see all of the effort put into camera reviews back then. This is especially true as I’m just some guy with a blog that picks up an old camera, shoots a couple of rolls of film through it, and then writes what I think about it online. What I consider an objective test is such a far cry as to what these men and women used to do, that I should probably stop calling what I do as “reviews”.

With the disappearance of print magazines in favor of instant gratification web blogs and social media posts, in depth tests like these are becoming fewer and farther between. Every month, when a new issue of Modern Photography or some other magazine hit the newsstands, you were assured that testing like that covered in this article was performed on anything before you bought it, but that’s no longer true.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2020.

Thanks for posting, this is really interesting! Especially since I’m currently writing a review of a vintage lens for Casual Photophile and trying to come up with simple tests which I can do at home without expensive equipment, even though they are not nearly as rigorous as what the Modern Photography article describes, or what the folk at lensrentals do for example.

And I would say the type of reviews you do have a lot of value too, especially when it comes to vintage cameras. Many of us are less interested in sharpness and other such parameters, more about the history, design, and feeling some sort of emotional connection to the mechanical objects. I’ve learned a lot from your reviews.

On the other hand, people who are in the market for digital cameras and lenses often seem more interested in the sort of things Modern Photography was testing for. And websites which cater to digital photographers tend to lean more towards testing, quantification, etc., which makes sense.

I appreciate the feedback from one reviewer to another! 🙂