For as long as people have been on this planet, we have been looking at the skies, and for as long as people have had access to cameras, we have been trying to take photographs of it.

Every year there is some celestial event such as the recent Perseid Meteor Shower, lunar eclipses, solar eclipses, Aurora Borealis, blood moons, super moons, super-blood moons, comets, planets, and other distant galaxies. For someone not familiar with how photography works, taking a photograph of something in the night time sky probably seems as easy as pointing a camera up and pressing the shutter release, but the reality is that there is much more to it.

The beauty about using vintage cameras is that the principles for photography have largely stayed the same between the film and digital age. Many of the same rules and guidelines that once applied decades ago, still hold true today, so it was with great fascination when I came across this article from the September 1960 issue of Modern Photography with tips on taking photos of outer space from your back yard.

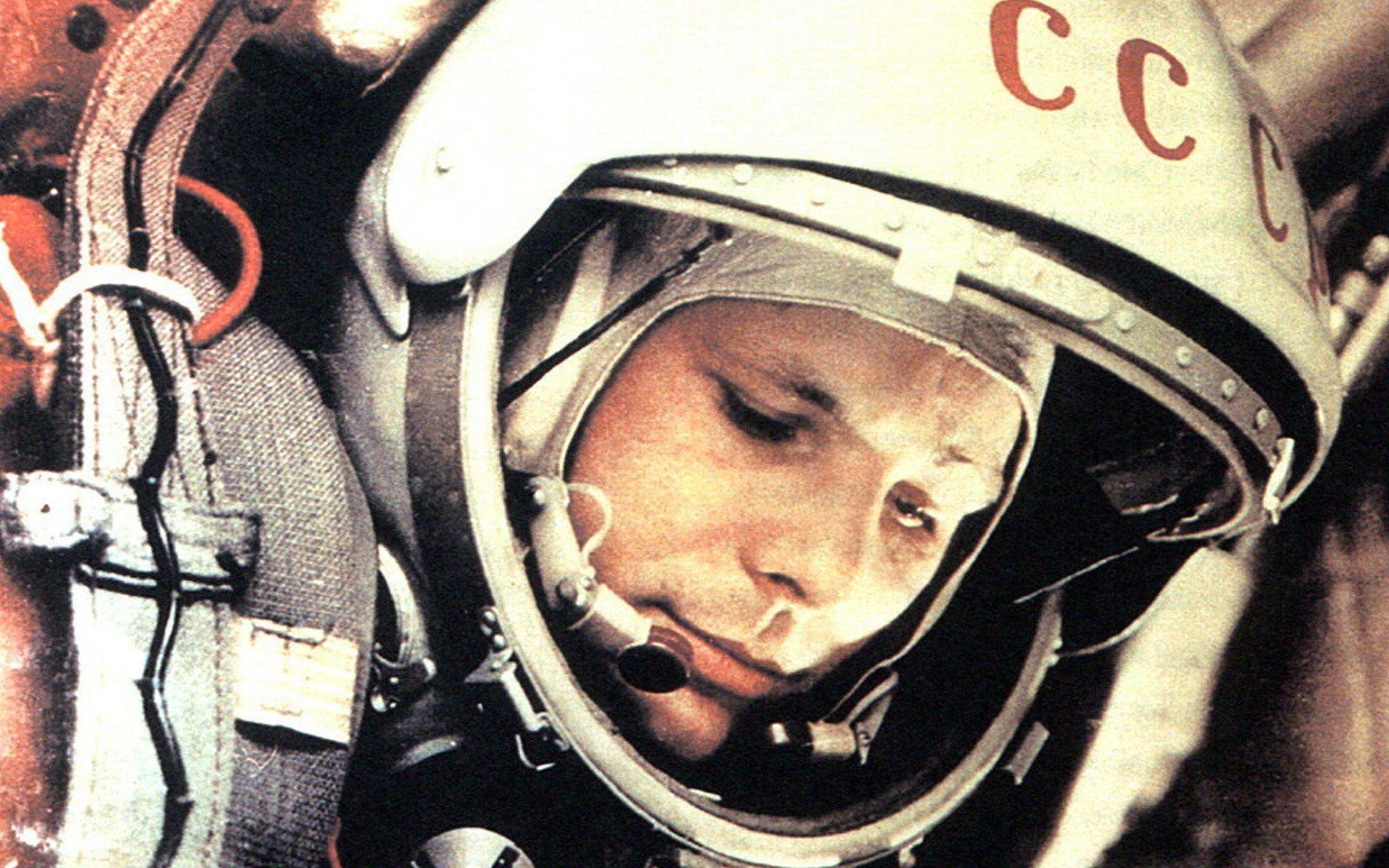

When this article was written, our knowledge and experience in outer space was on the verge of many major breakthroughs. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin hadn’t yet walked on the room, Yuri Gagarin hadn’t yet completed mankind’s first space flight, and Ham the chimpanzee hadn’t been the first hominid in space. Although each of these major milestones were only a short while away, we were still fascinated by the stars and planets and wanted to make our own photographs of them.

This article serves as an introduction to shooting outer space from your backyard, and goes over which lenses you should use, how to stabilize your camera, what kinds of films to use, and other techniques to maximize your chances at success. Other than a choice of film, pretty much everything in this article would apply to modern digital photography as well, so even if you’ve made it here and don’t shoot film, the majority of the information in this article still applies today.

I’ve tried taking photographs of the night time sky with my own cameras, and something that has challenged me was how to get a photo of stars and constellations using long exposure times without having them blur to the rotation of the earth. It turns out there is a formula for that, which this article covers. For extremely long exposure times needed to capture the galaxies and far away planets, you need some type of motorized rig to keep your camera moving in relation to the apparent movement of the sky. Perhaps you want to make star trail photos, you can do that to.

Whether you’re an advanced photographer using the best digital cameras, or the largest sheet film cameras, or someone using an inexpensive point and shoot film camera, you can take photographs of things beyond our world too. While this article doesn’t cover everything, it is a good start, and reading it for this article has already made me want to get out my tripod and shoot some moon pictures!

A word of clarification about the article below is that there is a mini article within the main article that covers photography with a telescope. The way the images appear in the gallery below can get a bit confusing, but just know that the telescope mini-article is all of the text in bold. Everything not in bold is of the main article.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2018.