Good news everyone! Rangefinders are back!

Wait a minute, where did they go?

I guess a bit of perspective is due here. Prior to the early 1950s, the SLR was a niche product. The Ihagee Exakta was the only major 35mm SLR system around, and it was very expensive (yes, I know about the Alpa, Rectaflex, and Zeiss Contax prototypes). The Japanese market was still in it’s infancy and most new Japanese models were heavily inspired by existing German rangefinder, TLR, and view camera designs.

Over the course of the next few years however, there was a huge swing in camera technology. By 1958, Asahi Pentax, KW Praktina/Pentacon, Miranda, Tokyo Kogaku (Topcon), and Chiyoda Kogaku (Minolta) had all released new 35mm SLR systems.

For the consumer around this time, it must have seemed like the SLR invasion was upon them. Gone were the hordes of Barnack inspired rangefinders with their split windows and tiny non-parallax corrected viewfinders, the days of through the lens composition was upon them!

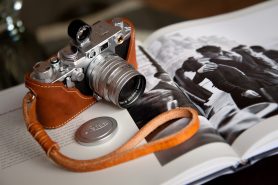

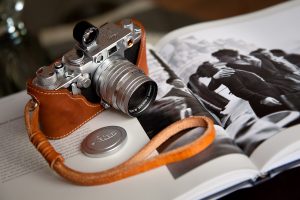

This article from the February 1958 issue of Modern Photography was here to remind the public that not only were rangefinders still around, but they had gotten a lot better. New designs from Leitz, Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), Canon, and Zeiss-Ikon were here with larger and brighter viewfinders with combined coincident image rangefinders. New features like parallax corrected projected frame lines and adjustable focal lengths were available meaning that a rangefinder camera could be used with some of the same flexibility as the new SLRs and users (like me) with prescription glasses could more easily see the whole frame.

The 1950s pre-dates our current disposable culture where every 2 years we’re looking for the latest and greatest smartphones, and every 5 or so years looking at new 4K HDTVs, digital cameras, laptop computers, and video game consoles. Things were built to last back then and it wasn’t unusual for a photographer to buy a new camera and keep it for 10, 20, or even more years. So with the huge advances that occurred during the 50s, it probably was worth creating an article like this that let people know that modern rangefinders were not like the ones available in the previous decade.

In Mike’s Guide to Buying Old Cameras, I make an attempt to explain how a rangefinder works, but this article below does a far better job than I ever could. The article has really good illustrations of 8 different popular designs for rangefinders that were found in models like the Zeiss Contax, Argus C-44, Retina IIIc, and Nikon SP.

I found it particularly interesting the praise that a camera like the Argus C-44 was given for having not only a similar rangefinder design to the Leica M3, but also that it was heralded as having a surprisingly bright viewfinder for the era. I have a C-44 in my collection that I have yet to review, but after reading this, I feel compelled to move it up in the queue.

This article answers other interesting questions like what the coating on a beamsplitter is made of, why a wider rangefinder base is better than a narrower one, and also why you won’t ever see a rangefinder designed for a lens any wider than 35mm or longer than 135mm. This is one of the more technical Keppler’s Vault articles I’ve highlighted, but it’s very fascinating if you like to know how these things work, and for the few of you out there who have never given a rangefinder a chance, this article might change that!

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2018.