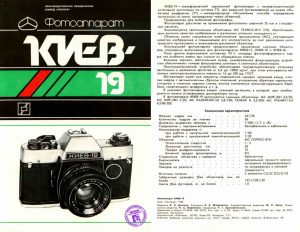

This is a Kiev-19, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by the Arsenal Factory in Kiev, Ukraine between the years 1985 to 1994. It was a replacement to the earlier Kiev-17 which was the first Soviet camera to use Nikon’s F bayonet mount. Most Nikon F-mount lenses will work correctly on this camera, as will the Helios-81M lens work on most Nikon bodies. This particular model featured a TTL CdS meter with red LED over/under match lights to be used to measure exposure, but the camera did not feature any kind of automatic exposure. The camera is fully mechanical and only uses the batteries to power the meter. The Kiev-19 was the most successful and longest lived of the entire Kiev 35mm SLR series, being one of the few Soviet cameras to stay in production after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

This is a Kiev-19, a 35mm Single Lens Reflex camera made by the Arsenal Factory in Kiev, Ukraine between the years 1985 to 1994. It was a replacement to the earlier Kiev-17 which was the first Soviet camera to use Nikon’s F bayonet mount. Most Nikon F-mount lenses will work correctly on this camera, as will the Helios-81M lens work on most Nikon bodies. This particular model featured a TTL CdS meter with red LED over/under match lights to be used to measure exposure, but the camera did not feature any kind of automatic exposure. The camera is fully mechanical and only uses the batteries to power the meter. The Kiev-19 was the most successful and longest lived of the entire Kiev 35mm SLR series, being one of the few Soviet cameras to stay in production after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Film Type: 135 (35mm)

Lens: 50mm f/2 MC Helios-81N (Гелиос-81Н) coated 6-elements

Lens Mount: Nikon F Bayonet (non-Ai)

Focus: 0.5 meters to Infinity

Viewfinder: Pentaprism Reflex Finder

Shutter: Vertically Traveling Focal Plane

Speeds: B, 1/2 – 1/500 seconds

Exposure Meter: TTL CdS Cell w/ Viewfinder +/- Readout

Battery: 2 x LR44/357 1.5v Batteries

Flash Mount: Hotdshoe and PC Flash Sync

Weight: 708 grams (body) / 918 grams (w/ lens)

Manual (in Russian): http://ussrphoto.com/Wiki/Content/files/671/Kiev_19_manual.pdf

Manual (Kiev 19M in English): http://www.cameramanuals.org/russian_pdf/kiev_19m.pdf

How these ratings work |

The Kiev-19 is an all mechanical 35mm SLR built by the Arsenal factory in Kiev with a TTL CdS exposure meter and a Nikon F bayonet mount. Although able to use Nikon lenses, this is no Nikon clone. The camera is very rudimentary and offers no automation, an exposure reading can only be taken with the lens stopped down, and has a limited number of shutter speeds. Although produced for nearly a decade from the mid 80s to mid 90s, the camera’s feature set is more comparable to early 70s SLRs. Yet, despite what looks to be a forgettable camera on paper, turns out to be a really nice little camera. Everything on it worked well, the viewfinder is large and bright, and the Helios-81N lens produced spectacular results. | ||||||

| Images | Handling | Features | Viewfinder | Feel & Beauty | History | Age | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0% | |

| Bonus | +1 for the complete package, this was a fun camera that I couldn’t put down | ||||||

| Final Score | 9.0 | ||||||

History

The Arsenal factory in Kiev, Ukraine has a long history dating back as far as 1764 as a repair and production facility for the Russian military. It would change locations a number of times and by the early 20th century would grow into one of the Soviet Union’s largest manufacturing facilities.

The Arsenal factory in Kiev, Ukraine has a long history dating back as far as 1764 as a repair and production facility for the Russian military. It would change locations a number of times and by the early 20th century would grow into one of the Soviet Union’s largest manufacturing facilities.

Prior to World War II, Arsenal produced a variety of military goods, but little to nothing for the civilian market, and certainly no cameras. After the war, when the Soviet Union took over what became East Germany, they seized much of the manufacturing equipment and spare parts from various Dresden area camera manufacturers like Zeiss-Ikon and transported it to Kiev.

The Soviet Union was no stranger to building their own cameras based on German designs. In the 1930s, another Ukrainian factory in Kharkov, Ukraine called FED had produced a copy of the Leica II rangefinder made by Leitz of Wetzlar. The FED copies were entirely built using Soviet machinery and technicians as they would have not had access to the original designs or tools from the Wetzlar factory.

At the same time Leitz was building the Leica, Zeiss-Ikon had a competing 35mm rangefinder called the Contax. Since the Soviets now controlled East Germany where the Contax was built, they were in the unique position to use the actual machines, tools, and some of the workers from the Zeiss factory to resume production of their own version of the Contax, which they would call the Kiev.

The first Kiev camera was called the Kiev II, due to it being an exact replica of the Contax II (there was never a Kiev I). In fact, calling the Kiev II a replica of the Contax isn’t entirely accurate as many of the very first models were built using spare parts built in Germany for the Contax. If you take apart an early Kiev II and look behind the name plate, you’ll see the original stamping that said Contax, which was later flattened, and restamped with the Kiev logo.

In addition to using original Zeiss spare parts, the Arsenal factory used the original Zeiss tools to make new Kiev parts. These weren’t simple copies, they were the real thing, just made in a different location.

Arsenal would produce the Kiev II and later the III and 4 models until the late 1980s. Over time, very little of the camera changed from that original design. You can put a Kiev 4M built in 1987 side by side with a pre-war Contax II and there is still a very strong resemblance between the two.

Along with the Kiev/Contax cameras, the Arsenal factory would build a variety of other cameras, most based off existing designs by other companies, but none using the original machinery like the Kiev rangefinder. These other cameras like the Hasselblad inspired Salyut from 1957, the Minolta 16 inspired Vega from 1959, the Pentacon Praktisix inspired Kiev 6c from 1971, and the Minox 35EL inspired Kiev 35A from 1985 all looked very similar to the models which they were inspired off, but were all simplified and less expensive copies. Many of these Kiev copies had a poor reputation for build quality, but due to their cheap cost, are often sought out as inexpensive alternatives to the original designs.

Perhaps one of the Arsenal’s most ambitious designs was a new 35mm SLR camera called the Kiev-10 which was released in 1964. The Kiev-10 not only had a design that was unique to any other camera in the world, it had a unique shutter not seen on any other camera, it used it’s own bayonet lens mount, and was also the first Soviet SLR with automatic exposure. A new model called the Kiev-15 debuted in 1973 replacing the large selenium cell with a TTL CdS meter, but the camera was otherwise the same.

For as ambitious as the Kiev-10 and 15 were, they were rather expensive for the Soviet domestic market and sold poorly. In an effort to increase sales both in the Soviet union and abroad, in 1975 another all new camera called the Kiev-17 would be released that had a much more traditional “Western” design, and used the Nikon F-mount. The F-mount was likely chosen as it had been the most successful lens mount for professional photographers of the 1960s and early 70s due to the massive success of the Nikon F and F2 SLRs. The use of the F-mount meant that almost every lens created for the Nikon could instantly be used on the new Kiev camera.

The Kiev-17 was a fully mechanical camera with no metering and although wasn’t based off any existing Nikon design, it is said that is somewhat resembles a less refined version of the Nikkormat. After it’s release, there would be a couple prototypes created that updated the feature set, but none were ever released to the public.

It wouldn’t be until 1985 that a new 35mm SLR would be available with the Kiev name. The Kiev-19 added a TTL CdS meter with red LEDs visible in the viewfinder for exposure measurement and had a revised body design that was lighter and less expensive to make. The Kiev-19 also eliminated both the 1 and 1/1000 second shutter speeds available on the 17. Despite these changes, the Kiev-19 turned out to be a very popular camera, staying in production for nearly a decade.

The Nikon F-mount was usually limited to only Nikon cameras, with only a single model by Ricoh and a few digital cameras by Fuji and Kodak that used the mount. The Kiev-17 and 19 family of cameras are the rare exception of a completely unrelated camera to share the mount, and for that have a certain level of collectability.

Today, I don’t know that there is a huge market for these cameras as Nikon made so many inexpensive F-mount cameras that there’s not a huge demand for cheap Soviet alternatives like there might be for Leica or Contax clones, but for those who have a large library of Nikon lenses and like something different, these are interesting cameras to add to your collection.

My Thoughts

I love Nikon film cameras. I love Soviet cameras, but a Soviet camera that accepts Nikon lenses?!?! TAKE MY MONEY!!!!

In all seriousness, I had been aware of these Nikon F-mount Kiev SLRs for quite a while but strangely, it was a recent Kickstarter campaign created by a German company called Net SE, who recently attempted (and failed as the company has since gone bankrupt) to “re-introduce” several, formerly prominent camera marques into the 21st century. One particular model was one they called the Ihagee Elbaflex. Ihagee, of course, was the name of an innovative German camera maker who was responsible for the long lived Exakta series. The name “Elbaflex” was a name used on a couple of Exakta models made in the 1960s to be sold for export to countries where the Exakta name was forbidden.

If the thought of a modern “re-release” of an Exakta based camera made in the 21st century sounds exciting for you, prepare to be disappointed because this new Elbaflex wasn’t based off the Exakta, or anything Ihagee had ever made. In fact, despite the Kickstarter promotion claiming that the camera was created by “German and Ukrainian engineers”, the camera was almost entirely Ukrainian. It wasn’t even a NEW Ukrainian camera…it was simply a rebadge of an old one…from 1988…called the Kiev-19M.

The Kiev-19M was the last in the Kiev SLR series, and improved upon the Kiev-19 with open aperture metering and adding a hand grip. The Ihagee Elbaflex was literally the same camera, just with a new name and a wooden hand grip (maybe that’s the part created by ‘German engineers’).

Not exactly wowed by this “all new mechanical film camera created by German and Ukrainian engineers”, and certainly not by it’s estimated $1500 retail price, I quickly turned my attention to the camera that it was based off.

The Kiev-19 was the longest produced in the entire Kiev SLR series, and had a feature set that compared similarly to early Nikkormat cameras, specifically the FT3. Compared to that camera, both have vertically traveling metal blade shutters, a TTL CdS meter with a match LED display (the Nikkormat uses a needle) in the viewfinder. Both accept the same range of Non-Ai, Ai, and Ai-S lenses, and both used 1.5v silver-oxide or alkaline batteries to power the meter.

Unlike the Nikkormats however, the Kiev had a more limited range of shutter speeds (lacking 1 and 1/1000 seconds), and only supported stop down metering. Since the Kiev could not meter with the lens wide open, the only way to get a reading is to press the stop down lever on the side of the lens mount with the camera to your eye.

I didn’t actually have access to an FT3, so I chose the next best thing, a Nikon EL2 which was the successor to that model. Although the EL2 is a much more advanced camera with a full information viewfinder, automatic exposure, and an electronic shutter, all of the electronic aides can be disabled, and the build quality between the EL2 and FT3 are comparable, so I thought it would be a fair comparison.

Starting with build quality, the Kiev is noticeably rougher, especially in the film advance. Where the Nikon (and pretty much every mechanical Nikon) has a smooth and fluid motion to the advance lever, the Kiev’s felt both loose, and overly tight at the same time. Tension on the lever changes midway through the advance, as if you could feel the metal gears inside of the camera moving the shutter curtains and getting it ready for the next shot. The wind lever on the Kiev is strangely shorter than that of the Nikon, and even the Kiev-17 which it replaces.

There is also a bit of play in many of the camera’s controls from the front mounted shutter speed dial and both the plastic stop down and lens release levers. The use of plastic on this camera concerns me, especially for the stop down lever, which would likely get a lot of use from someone who relied on the meter for exposure measurement. Although neither of these levers were broken on the example I had, it’s not a stretch to think that there were probably a good number of these cameras where these plastic levers broke off.

Thankfully, the viewfinder on both cameras are both large and bright, featuring a split image focus aide with microprism collar around it. The Kiev’s microprism collar is slightly larger than the Nikon’s and the whole viewfinder on the Kiev had taken on a yellowish tint, whereas the Nikon’s was still clear with no tint. The yellowish tint of the Kiev’s could be due to age as plastic focus screens on many cameras sometimes turn yellow due to exposure to light. Whether it was like this when the camera was new is anyone’s guess, but it hardly affects the ability to properly see focus. The only exposure information is through a red + and – LED on the left side. Although the + is lit up in my example, it never changed no matter how much light there was, suggesting the meter is malfunctioning in my example.

Loading film into both cameras is straightforward. A gentle upward tug of the rewind knob and the right hinged door opens. The plastic take up spool on the right has multiple slots in it and allows for quick and easy loading of a new roll of film. Although the shutter in the Kiev-19 is a vertically traveling focal plane, it only has two blades, as opposed to others such as those designed by Copal, which have several.

So far, I haven’t mentioned the most notable feature of the Kiev-19, which is the Nikon F-mount and it’s Helios-81N lens. I want to point out that many English language posts incorrectly call this lens the Helios-81H, since there is what looks to be a Roman letter “H” on the lens ring. In reality, what looks like an English H, when written in Russian is an “N”. If you would like to learn more about the history of the Helios 81-series, I recommended reading this article (in Russian, so you’ll need to use Google Translate).

Since the camera doesn’t support any kind of open aperture metering, the Nikon F-mount has absolutely no lens coupling of any kind, so that means there’s no “bunny ears” like many Nikon lenses had, and there is no auto indexing tab like on the EL2, so you can freely attach old “non-Ai” lenses without having to worry about compatibility. In fact, other than a few obscure specialty lenses that protrude into the mirror box, literally every Nikon F-mount film lens will physically attach to the camera. Even modern DX digital lenses will, but it’s not recommended as most do not have an aperture ring and will not cover the whole 35mm frame.

The Helios-81N lens is a 6-element design, and despite the Helios name, is a different optical formula than the Helios-44 which is popular for it’s unique out of focus characteristics. The most obvious reason for this is that the Helios-44 is a 58mm lens, and the Helios-81N is 50mm. The lens diagram to the left is from ussrlens.com and shows the makeup of the elements of a Helios-44, ultra-rare Helios-65 from the Kiev-10, and the Helios-81 used on Kiev 35mm SLRs.

If the Helios-81N was an actual Nikon lens, it would be considered an “Ai” or “Automatic Indexing” lens, which means it has a tab cutout near the lens mount that lines up with a “feeler tab” that allows the camera to detect the chosen f/stop on the lens. In the image to the right, the yellow arrow points to the “feeler tab” on the Nikon EL2. An earlier version of the Helios called the 81M also existed and was exactly the same, except it lacked the tab cutout for “Ai” cameras, and would have been considered a “non-Ai” lens. The Kiev-19 does not support the automatic indexing feature, so mounting either a Helios 81M or 81N lens makes absolutely no difference. Where it would be beneficial to have the 81N lens would be on the less common Kiev-20 or when using that lens on an actual Nikon SLR with the Automatic Indexing feature.

If the Helios-81N was an actual Nikon lens, it would be considered an “Ai” or “Automatic Indexing” lens, which means it has a tab cutout near the lens mount that lines up with a “feeler tab” that allows the camera to detect the chosen f/stop on the lens. In the image to the right, the yellow arrow points to the “feeler tab” on the Nikon EL2. An earlier version of the Helios called the 81M also existed and was exactly the same, except it lacked the tab cutout for “Ai” cameras, and would have been considered a “non-Ai” lens. The Kiev-19 does not support the automatic indexing feature, so mounting either a Helios 81M or 81N lens makes absolutely no difference. Where it would be beneficial to have the 81N lens would be on the less common Kiev-20 or when using that lens on an actual Nikon SLR with the Automatic Indexing feature.

Any quality concerns I had with the Kiev camera, do not extend to the Helios-81N lens. The build quality of the lens is on par with period Nikkor lenses. The body is entirely metal, with a deeply textured grip on both the aperture and focus rings. Focus movement is smooth and firm, without feeling tight. The aperture ring has reassuring click stops at every setting from f/2 – f/16. The lens coating has a nice shape of green and blue that shows no signs of yellowing as with other lenses from the era. My example had no oil or any kind of lubricant on the iris blades, and when activated, the lens stopped down quickly and without delay. Mounting the lens on the Kiev feels exactly the same as when mounted to an actual Nikon, and once it is locked into place, it is tightly secured, without any wobble.

The Kiev-19 is a bit of an enigma. These cameras were the only Soviet cameras to use the Nikon F-mount. Other than proprietary Soviet mounts like on the Kiev-10 and 15, or the KMZ Start, the only other 35mm Soviet SLRs with a bayonet mount were the LOMO Almaz series and the later Zenit SLRs with their Pentax K-mount. Aside from the mount, nothing else is shared with an actual Nikon, so this can’t be seen as a copy. Feature wise, this camera was very primitive, and even when comparing it to a mid-70s Nikkormat, it lacks things such as a 1/1000 top speed, open aperture metering, and full information display. The build quality of the camera doesn’t live up to Japanese standards, but the viewfinder is decent, and the lens is very nice.

My Results

For my first roll through the Kiev-19, I had this great idea to shoot a 36 exposure roll in the Kiev, and split it with the Nikon EL2 with a Nikkor 50/2 lens attached and do a comparison of the images shot in the Kiev and the Nikon.

A funny thing happened as I was going through the first 18 exposures. As it would turn out, I enjoyed shooting the Kiev so much, that I didn’t want to stop at the halfway point and once I had hit the 22nd exposure, I figured I might as well scrap my “split” plan and just finish the roll in the camera.

My favorite thing about collecting and shooting old cameras are those moments when one particular model surprises you in some way. Whether it’s a unique feature that is uncommon in other cameras, or images that are unexpectedly better than you had anticipated, or other times its just when everything comes together to a pleasant shooting experience.

I really enjoyed the experience with the Kiev. Was there anything particularly unique or special that I couldn’t have experienced with any other number of mechanical 35mm SLRs? Not really. I guess I just like the underdog. For once, a Soviet camera just worked. There wasn’t any hard and fast rule about when I could change shutter speeds, I never needed to squint when looking through the viewfinder, every single control (well except for maybe the shutter speed dial) is where it was on most every other 35mm SLR from the era, and….that lens!

I had high hopes for the Helios-81N, and I was impressed with the build quality, but once I saw the images, I was very impressed at the quality of the Soviet glass. If I had anything to be disappointed at, is maybe the images were “too perfect” in the sense that there was no unique bokeh or characteristic vignetting that you sometimes get in other Soviet lenses. I really think that had I gone through with my original idea of splitting this roll of film with the Nikon camera and it’s Nikkor lens, I really would not have seen any difference in the images.

Overall, I am very impressed with the Kiev-19. As much as I enjoy strange and quirky cameras, Soviet cameras all seem to fall into one of two categories, blatant ripoffs of German designs, or extremely oddball cameras that eschew traditional design. The Kiev 19 is the rare example of a modern looking camera with good ergonomics, has excellent optics, and is a lot of fun to use. If you ever have a chance to pick one of these up, I recommend it!

Related Posts You Might Enjoy

External Links

http://www.sovietcams.com/index.php?-1968978777

http://camerapedia.wikia.com/wiki/Kiev-19

http://www.alexluyckx.com/blog/index.php/2019/02/13/camera-review-blog-no-102-kiev-19/

http://www.commiecameras.com/sov/35mmsinglelensreflexcameras/cameras/kiev/index.htm

https://www.lomography.com/magazine/192736-kiev-19-the-ukranian-beast

http://lensbeam.com/obzory-fotoapparatov/fotoapparat-kiev-19-obzor-i

Thanks for the review. I have a Kiev-19 and 19M (both export versions; my 19 is black and lacks the split-image focusing aid) and they are sturdy, reliable SLRs with good lenses.

In your write-up, you describe the 19M as a “scaled-down Kiev-19 without a meter.” The 19M has open-aperture metering with the same LED display in the viewfinder as the 19, and the same dimensions, but is a bit lighter due to the use plastic body covers. The Kiev-19 is really a simplified version of the Kiev-20. There was also a Kiev-18, with auto exposure, motor drive capability, and came with a 1.4 lens, but it is unclear if it ever reached production.

Also, there were two other Soviet SLRs which shared a unique lens mount, the Zenit-7 and Zenit-D, but both of these are quite rare. Information on these and many other fascinating cameras can be found in Jean Loup Princelle’s “The Authentic Guide to Russian and Soviet Cameras.”

Dave, thanks for catching that! I have edited the post and corrected my mistake. Perhaps I bumped my head that day when I wrote that as I have no idea where I got that from. Amazingly, no one in the 2.5 years since I posted that review has pointed it out to me! If you see any other mistakes in any other reviews, please let me know!

The viewfinder of kiev-19 is in the middle of the body, too close to the knob. it is annoying when you want to take another pic at a time.