The first 5 words of the article below from the February/March 1962 issue of Camera 35 magazine are:

The Alpa Reflex is expensive…

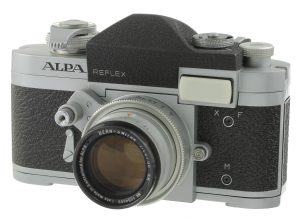

Talk about the understatement of the year! According to this article, in 1962 an Alpa 6C with 50mm f/1.8 Macro-Switar Apochromat lens retailed for $469. When adjusted for inflation, that’s nearly $4000 today, and while used examples of the Alpa 6C dont quite fetch those prices today, they still very easily cross the 4-digit threshold in good working condition.

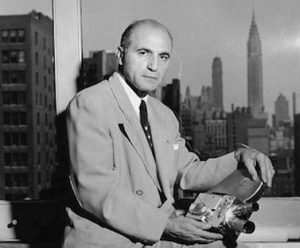

A short history of Alpa, is that it is a brand name of quality cameras made by the Swiss company Pignons S.A. in Ballaigues, Switzerland in the early to mid 20th century. The original design for the Alpa Reflex was created by a Russian Jew named Yakov Bogopolsky (later Jacques Bolsey). Prior to the Alpa, Bolsey created music boxes and the Paillard Bolex motion picture camera. I’ve covered more about Bolsey’s history and what he did after creating the Alpa in my review for the Bolsey B2.

The Alpa Reflex was an unusually well made camera consistent with the quality reputation of other Swiss watchmakers. Most Alpas were hand made in very limited numbers and were always very expensive.

Despite the number ‘6’ in the name, the Alpa Reflex 6c was the first of the third generation of Alpa SLRs released in 1960. The 6c had a redesigned body from earlier models and was the first Alpa model to feature a built in selenium exposure meter, taking the place of the straight through optical viewfinder which was a trademark feature of earlier Alpas.

The article below from the February/March 1962 issue of Camera 35 magazine spends quite a bit of time going over the many different reasons that the Alpa stands out from the competition, including it’s extremely bright and easy to use pentaprism viewfinder, soft rubber coated eyepiece, unique film advance, and several “in between” shutter speeds like 1/3, 1/6, 1/70, 1/90, and 1/160 in an effort to give photographers more precise control over their exposures.

Not ever having the opportunity to shoot with an Alpa, I found it interesting how the author of this article attempts to take things that would otherwise be considered ‘cons’ and spin them in a way to sound like a benefit. He argues that the uncoupled meter should be seen as a benefit because if you choose to ignore it, it won’t get in the way, and the externally coupled automatic diaphragm is better because it allows you to see the iris begin to stop down before firing the shutter. I’ve never really put much thought into whether an uncoupled light meter or the large button on an externally coupled diaphragm could be seen as benefits, but Mr. Kramer seems to think so. Whether he’s an old school stalwart of pre-automation days or is just really good at “turning lemons into lemonade” is anyone’s guess.

I don’t want to repeat too much of what is in the article as it’s a fascinating read not only for collectors of Alpa cameras, but for those like me who may likely never get a chance to shoot with one. While there were a lot of very expensive cameras made in the 20th and 21st centuries, not all of them can claim the high number of custom features that weren’t found on other models of the era. I can’t say that if I was a photographer in 1962 I would have spent $469 to buy one, but at least if I had, I would have had a camera unlike any other.

All scans used with permission by Marc Bergman, 2018.